But football was played and results depended largely on momentary strength of a team, for the only club which had something like long-term plan was Cosmos. Rochester Lancers, Atlanta Chiefs, Seattle Sounders, Portland Timbers, New England Tea Men, Memphis Rogues, Edmonton Drillers, and San Jose Earthquakes were the teams eliminated after the first phase of the championship finished. Cosmos had the best record of all clubs, finishing with 216 points.

In the next stage things changed a bit – direct elimination took no account of any previous performance. Houston Huricane, the team with second best record in the first phase, lost both legs to Philadelphia Fury, which was 3rd in their original Eastern Division of the American Conference and the team with the worst record in the first phase – they got 111 points, which was less than all 4th-placed clubs in the National Conference. In fact all pairs at this stage had stronger team, winning both legs. The worst team at this stage was California Surf – they were champions of their division, but now lost 2-4 and 2-7 to San Diego Sockers. Three matches were decided in overtime, the most dramatic was the victory of Tulsa Roughnecks over Minnesota Kicks: both legs went into overtime, eventually the Roughnecks prevailing both times 2-1.

The Conference ½ finals followed and here two teams were eliminated, which in another country could have been a surprise.

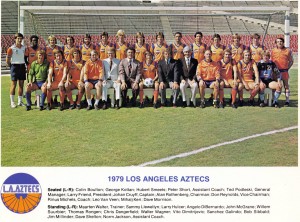

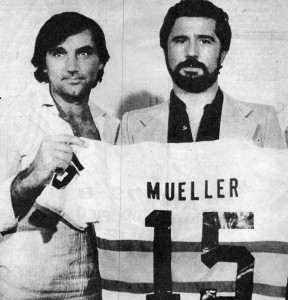

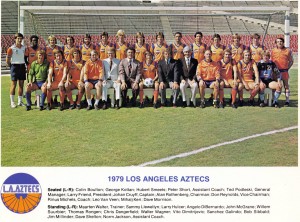

Los Angeles Aztecs, lead by Michels and Cruyff, looked like a team aiming at the title. However, they were eliminated by Vancouver Whitecaps – a club with may be too much British flavour to be considered stronger than fashionable Dutch. It was strong and dramatic battle, though: each opponent won a leg, but the match in Los Angeles went to a shoot-out to brake the tie. The rule of third mini-match was applied after the two legs and Vancouver won it 1-0. Cruyff was asked about his impression of NASL and his future – he said he will play one more year in North America and retire for good. Definitely. Remember this statement.

Los Angeles Aztecs, lead by Michels and Cruyff, looked like a team aiming at the title. However, they were eliminated by Vancouver Whitecaps – a club with may be too much British flavour to be considered stronger than fashionable Dutch. It was strong and dramatic battle, though: each opponent won a leg, but the match in Los Angeles went to a shoot-out to brake the tie. The rule of third mini-match was applied after the two legs and Vancouver won it 1-0. Cruyff was asked about his impression of NASL and his future – he said he will play one more year in North America and retire for good. Definitely. Remember this statement.

One more match was decided by shootout – the first match between Philadelphia Fury and Tampa Bay Rowdies. Tampa Bay won both legs at the end. New York Cosmos had troubles against Tulsa Roughnecks – the opponents won their home legs 3-0 each and once again a mini-game was scheduled: this time Cosmos won 3-1.

The last pair gave the second surprise:

Judging by the squad, Chicago Sting was favourite. But they were unable to score even a single goal and lost both legs to San Diego Sockers.

Judging by the squad, Chicago Sting was favourite. But they were unable to score even a single goal and lost both legs to San Diego Sockers.

Thus, the Conference finals opposed San Diego Sockers to Tampa Bay Rowdies for the title of American Conference, and New York Cosmos to Vancouver Whitecaps for National Conference championship final. Third match decided both winners: Vancouver and San Diego won their home leg, but lost after shootout the second. Tampa Bay eliminated San Diego in the third mini-match 1-0, but the other Conference final had no winner and went to yet another shootout. Vancouver won it 3-2.

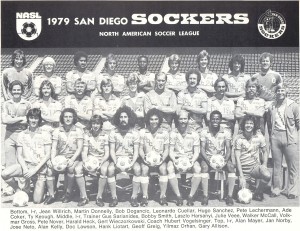

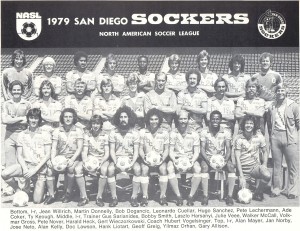

San Diego Sockers, perhaps the least impressive squad of the Conference finalists, still had players familiar with success: Harsanyi was part of the strong Ujpesti Dosza team of mid-1970s, Gross reached the UEFA Cup final with Twente and even played a match for the national team of West Germany in 1970. The real stars were Cuellar and Sanchez, who came on loan from UNAM. But that was nothing compared to the other loser.

San Diego Sockers, perhaps the least impressive squad of the Conference finalists, still had players familiar with success: Harsanyi was part of the strong Ujpesti Dosza team of mid-1970s, Gross reached the UEFA Cup final with Twente and even played a match for the national team of West Germany in 1970. The real stars were Cuellar and Sanchez, who came on loan from UNAM. But that was nothing compared to the other loser.

Cosmos’ squad was formidable and compared to any other – unbeatable. It was perhaps the only NASL team, not just a few old stars and bunch of so-so players. But Beckenbauer and Co. lost.

Cosmos’ squad was formidable and compared to any other – unbeatable. It was perhaps the only NASL team, not just a few old stars and bunch of so-so players. But Beckenbauer and Co. lost.

So, on September 8 Vancouver Whitecaps and Tampa Bay Rowdies met at Giants Stadium, East Rutherford, to decide the championship. Soccer Bowl’79. Over 50 000 attended – the record attendance of the season was much higher, but still it was huge crowd for a country not concerned with this kind of football. Trevor Whymark gave the lead to Vancouver in the 13th minute. Van der Veen equalized in the 23rd minute. In the second half Whymark scored his second goal in the 60th minute and since no more goals were scored Vancouver won 2-1. The new NASL champions hailed from Canada.

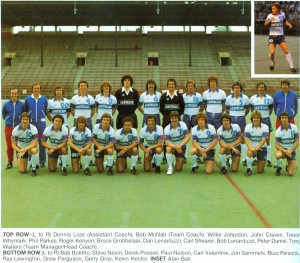

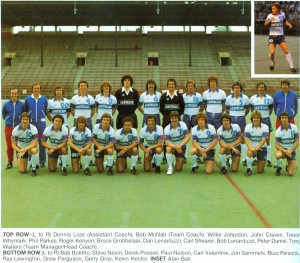

Tampa Bay came close to winning the championship, ending a strong season – they won their division, and did not lose a match in the play-offs – not in regular time, that is. But they were not as solid team as Vancouver. The stars of the team were of smaller status: Rodney Marsh (England) – a lesser version of George Best on and off the field, Mirandinha (Brazil), who played at the 1974 World Cup, but was never called to play for Brazil after that, Arsen Auguste (Haiti), who also played at the 1974 World Cup, Peter Baralic (Yugoslavia), a former regular of Crvena zvezda (Belgrade), but never a national team player, Jan van der Veen (Holland), who played for various Dutch and Belgian clubs, but not the big ones. The best player this year was Oscar Fabbiani, born in Argentina, but when playing in Chile became Chilean citizen and national team player, including at 1979 Copa America – Fabbiani was not wold famous, but finished as the top striker of NASL this season.

Tampa Bay came close to winning the championship, ending a strong season – they won their division, and did not lose a match in the play-offs – not in regular time, that is. But they were not as solid team as Vancouver. The stars of the team were of smaller status: Rodney Marsh (England) – a lesser version of George Best on and off the field, Mirandinha (Brazil), who played at the 1974 World Cup, but was never called to play for Brazil after that, Arsen Auguste (Haiti), who also played at the 1974 World Cup, Peter Baralic (Yugoslavia), a former regular of Crvena zvezda (Belgrade), but never a national team player, Jan van der Veen (Holland), who played for various Dutch and Belgian clubs, but not the big ones. The best player this year was Oscar Fabbiani, born in Argentina, but when playing in Chile became Chilean citizen and national team player, including at 1979 Copa America – Fabbiani was not wold famous, but finished as the top striker of NASL this season.

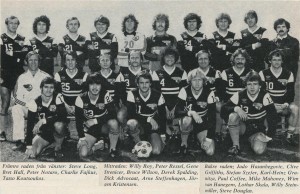

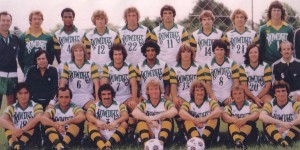

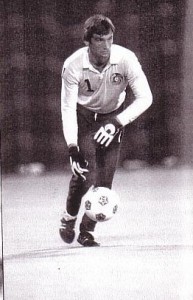

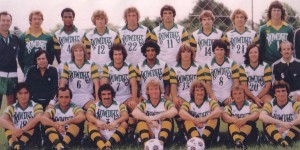

Vancouver Whitecaps enjoyed wonderful season, crowned with the title. Perhaps they were the team with the best chemistry in the league: largely English squad plus few good Canadian players familiar with British football, coached by English coach. No language problems, familiar tactical approach, familiar training, good fighting spirit. A few Canadian legends practically established themselves this year – Bob and Dan Lenarduzzi, Carl Valentine and Tony Waiters, the coach. Bruce Grobelaar, a reserve keeper still, got his introduction to big football and soon became famous with Liverpool. That was the legacy of this team – its real strength in 1979 was the British stars known for years already. Allan Ball (b.1945), world champion of 1966 with 72 caps and 8 goals for England, Kevin Hector (b. 1944), English champion with Darby County and 2 caps, Trevor Whymark (b. 1950) was a regular with constantly improving in the 1970s Ipswich Town and played 1 match for England, Phil Parkes (b. 1947), the goalkeeper of the strong Woolverhampton Wanderers side of the first half of the 1970s and also familiar with North American football, having played for US teams in 1967 and 1969, Willie Johnston (b. 1946), 21 caps for Scotland and long time key player of Glasgow Rangers, also ill-famed – he was tested positive for a banned stimulant at the 1978 World Cup and consequently expelled from the Scottish team. Finally, Bob McNab (b. 1944), well known from his years with Arsenal, having also 4 caps for England – his role was more or less symbolic, for he played only 3 matches for Vancouver in 1979 – two more than Bruce Grobelaar (b. 1957). Ball, Parkes, and Whymark were the key figures.

Vancouver Whitecaps enjoyed wonderful season, crowned with the title. Perhaps they were the team with the best chemistry in the league: largely English squad plus few good Canadian players familiar with British football, coached by English coach. No language problems, familiar tactical approach, familiar training, good fighting spirit. A few Canadian legends practically established themselves this year – Bob and Dan Lenarduzzi, Carl Valentine and Tony Waiters, the coach. Bruce Grobelaar, a reserve keeper still, got his introduction to big football and soon became famous with Liverpool. That was the legacy of this team – its real strength in 1979 was the British stars known for years already. Allan Ball (b.1945), world champion of 1966 with 72 caps and 8 goals for England, Kevin Hector (b. 1944), English champion with Darby County and 2 caps, Trevor Whymark (b. 1950) was a regular with constantly improving in the 1970s Ipswich Town and played 1 match for England, Phil Parkes (b. 1947), the goalkeeper of the strong Woolverhampton Wanderers side of the first half of the 1970s and also familiar with North American football, having played for US teams in 1967 and 1969, Willie Johnston (b. 1946), 21 caps for Scotland and long time key player of Glasgow Rangers, also ill-famed – he was tested positive for a banned stimulant at the 1978 World Cup and consequently expelled from the Scottish team. Finally, Bob McNab (b. 1944), well known from his years with Arsenal, having also 4 caps for England – his role was more or less symbolic, for he played only 3 matches for Vancouver in 1979 – two more than Bruce Grobelaar (b. 1957). Ball, Parkes, and Whymark were the key figures.

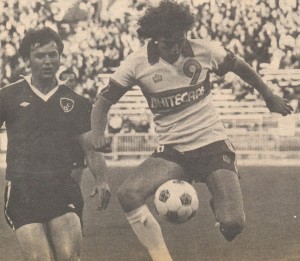

Vancouver bought Trevor Whymark for $300 000 from Ipswich Town – money well spent, for he scored both goals for his new club at the final and thus Vancouver won the title.

Vancouver bought Trevor Whymark for $300 000 from Ipswich Town – money well spent, for he scored both goals for his new club at the final and thus Vancouver won the title.

The stars were influential and inspirational, but it was a squad of similar minds: 12 English players, 1 Scot, 10 born or naturalized Canadians, and 1 player from South Africa/Zimbabwe – same language, same culture, same kind of football from coach to last reserve. Chemistry was perhaps essential for success.