After the enigma of Cruyff’s retirement it is only proper to introduce another enigma – a player praised as great hope debuted in 1977-78. However, very little can be said about him today – his career has many ‘blanks’… ‘Blanks’ from start to end and beyond. The name is Thomas Lafchis – or Laftsis… how his name appears in Latin alphabet depends on the original source – Lafchis, if it is transliterated from Bulgarian; Laftsis, if it is from Greek. He was born in August, 1958, in Sofia, Bulgaria, and gradually climbed through the youth system of Levski-Spartak (Sofia). He was noticed as a very talented junior, included in the first team, and quickly made great impression between the goalposts. The young goalkeeper was seemingly going to be a big star, surely a national team player, and who knows what else. By the end of 1978-79 he was already a champion and twice Cup winner – after such beginning sky was the limit. But his meteoric rise was followed… by sudden disappearance. A quick glance of his statistic record immediately brings problems – scarce information and mysterious too. For instance, Wikipedia gives two other clubs before his debut for Levski-Spartak – Cherno more (Varna) and Sliven (Sliven). How many matches he played for them? Unknown… Lafchis finished 1976-77 season captaining the juniors of Levski-Spartak. For the next season he was registered with the first team – if he was part of above mentioned clubs, it must have been between seasons, during the summer of 1977… when no matches were played, it was training and recruiting period, probably lasting less than a month, between vacation and registration of new squads for the upcoming season. A mystery… since both Cherno more and Sliven were military clubs at the time, it s possible that he went on trials there – talented young players often spent their military service as active players of military clubs. But both clubs were in the system of the arch-enemy of Levski-Spartak – CSKA – which makes it unlikely destination unless Levski was not interested in his own player. Normally, military service of Levski players went in the club – Levski belonged to the Police, which had its own militarized service. But Lafchis was an ethnic Greek – a fact, which by itself did not spare him from army service, but later development casts different light on the matter: Lafchis did not even artificially served in the Bulgarian army, apparently on the strength of foreign citizenship, probably obtained at about the time of his coming to military age. Was he ever with Cherno more and Sliven is very doubtful – he started the season as a player of Levski-Sparak, the club he started playing football as a kid. He just finished high school in the spring, so there was no even slight possibility he went to clubs in other cities earlier.

The new goalkeeper was universally seen as a back-up goalie – Levski-Spartak had the national team regular Stefan Staykov as a first choice. Youngsters were rarely given starting positions at 18 and goalkeepers even less so – Lafchis was perhaps to appear in a few matches, may be not even full games, but a few minutes here and there, against weak opponents, coming in as a reserve. May be not even that, because Staykov was in very good form and he played in the most matches of the national team in 1977. In general, Lafchis was expected to weight at the bench a few years, when he was to be more mature and experienced. But it was not so – he made very unusual debut in the fall of 1977 in the derby with CSKA. Youngsters without a single official game are the most unlikely choice for starting in a derby, but the circumstances were dire… A week before Levski-Spartak traveled to Amsterdam for the second leg of the 1/8 European Champions Cup with Ajax with only 12 players – the 12th was their single reserve, the second goalie Lafchis. The team was plagued by injuries and more players were added to the list after the matches with Ajax. For the derby Levski-Spartak scraped the very bottom… whoever was able to walk. The central defender Enchev was moved to midfield, just to make a starting eleven. Four players had no official match for Levski yet, among them – Lafchis. The improvised team was seen as sure loser… instead, they played fantastic match, annihilating CSKA 4-1. Lafchis was impressive between the goalposts – if so far he was seen as promising, but uncertain future player, now suddenly he was praised to the skies. However, in his first season he was still used sparsely – Staykov was the first choice. Lafchis ended his first season as a Bulgarian Cup winner, not bad for a start. His second year was vastly different – he edged Staykov from the regular place in the team, had a strong and unusually even for a young goalkeeper performance, and was expected to be called to the national team. Everybody was sure that he will be a long-lasting and solid addition of the national team – may be for the next ten or more years, what luck! Lafchis finished the season with a double… Staykov was reserve of Lafchis by now and how often an acting national team player sits on the bench of his club, a mere back-up of barely 20-years old?

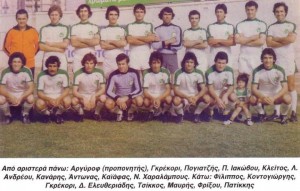

Levski-Spartak, a Bulgarian champion and Cup winner in 1978-79. Lafchis sitting in the middle of the first row.

Levski-Spartak, a Bulgarian champion and Cup winner in 1978-79. Lafchis sitting in the middle of the first row.

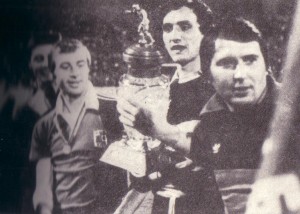

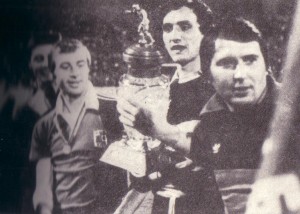

He was certainly becoming a star – this photo is telling: Lafchis with the championship trophy in his hands between Stefan Staykov and Pavel Panov (left). Taking the place of national team player and symbolically next to the greatest star and captain of Levski-Spartak of the 1970s, Panov. There was no doubt who was the next great player and it was not even a matter of time anymore.

He was certainly becoming a star – this photo is telling: Lafchis with the championship trophy in his hands between Stefan Staykov and Pavel Panov (left). Taking the place of national team player and symbolically next to the greatest star and captain of Levski-Spartak of the 1970s, Panov. There was no doubt who was the next great player and it was not even a matter of time anymore.

There was no Lafchis in the squad of Levski-Spartak for the 1979-80 season… no such player in any other team… Nothing. Not a word, not even a hint, in the press – it was like there had not been such player at all… Eventually, the grapevine cleared the mystery – to a point, because rumors are hardly the truth. Lafchis was allowed to repatriate (to emigrate is perhaps the more proper term, for he was born in Bulgaria) – there was already a precedent: back in 1975 highly talented young midfielder and Bulgarian national team player Kostas Isakidis was permitted to go to Greece. True to their vow of silence, the Communist authorities said next to nothing and only after months. No more news of Isakidis ever came… it was not a football transfer, for Communist Bulgaria did not export players, but ‘only’ permitting the ethnic Greek to move to his homeland. Of course, it had to do with football – Bulgarian Greeks were not permitted to move to Greece: rarely, particular individuals were quietly allowed to do so, but very rarely. Isakidis went to play of Aris (Thesaloniki)… and vanished. He made no impression in Greece, rather faded away – to a point, his problem was that he already played for Bulgaria and had no chance of ever becoming Greek national team player. Four years later Lafchis was let go the rumor made his case slightly different than the one of Isakidis: it was said that the permission was actually a deal between Panathinaikos, who wanted the talented player, and Levski-Spartak. A hidden transfer, for foreign transfers were officially impossible. Lafchis was in much better position than Isakidis – he moved to the biggest Greek club (according to the rumor) and since he never played for Bulgaria, most likely he was to be soon the national goalkeeper of Greece. A great future was envisioned: Greek football was rising, Panathinaikos was rich club, Lafchis, young, talented, and now in true professional situation was most likely to become not just Greek, but European star. Nothing was heard of him for years… star named ‘Lafchis’ never appeared. Instead, a quick look at his statistic record shows a gap… Lafchis debuted not in the fall of 1979, when he moved to Greece, but in 1981. Not for Panathinaikos either, but for the still virtually unknown outside Greece OFI Crete, a small club… There he stayed for the next two years, but… a next glance of statistics is in order: Lafchis played for OFI a total of 33 matches. Playing in less than 50% of the official matches of so-so club hardly suggests impressive career…

Lafchis eventually reached Panathinaikos – in the summer of 1983 and stayed with the club for two years.

Here he is a PAO player, but a star? Hardly… His numbers improved – 55 matches in two years, well over 50%, yet, not exactly overwhelming starter. May be adapting to life in Greece was difficult and halted his career, but if one traces his complete record… to the end of 1984-85 season Lafchis was never a regular – 27 matches for Levski-Spartak in 2 season, then 2 ’empty’ years, then 33 for OFI in 2 seasons, and 55 for Panathinaikos in 2 years. After 7 years of professional football, Lafchis achieved roughly a 50% average – certainly, a doubtful player, not a star… Greece had weaker goalkeepers than Bulgaria at the time, so the fact that he never appeared for Greece casts more doubts. And just when he seemingly came into some more reliable performance, he vanished again… after the end of 1984-85 season he was no longer part of Panathinaikos – most statistical records do not mention any club; Wikipedia places him in Belgium. A mystery again: just ‘a Belgian club’ is written, no name, no appearances… at least statistical records of the First Belgian league have no mentioning of such player. If he ever played in Belgium, it had to be in the lower divisions – clearly a step down… after playing for the top Greek club. He reappeared again in Greece – between 1987 and 1989 he played again for OFI Crete, a measly 15 matches. 30-years old he was retired from football… 130 matches in 12 years is nothing… was Lafchis just one of the countless failed players, who showed great talent at first, but quickly faded into obscurity? May be, but even this cannot be supported by evidence – very little is written about Lafchis: generally, only that he was a professional player. His current life is similar mystery.

Here he is a PAO player, but a star? Hardly… His numbers improved – 55 matches in two years, well over 50%, yet, not exactly overwhelming starter. May be adapting to life in Greece was difficult and halted his career, but if one traces his complete record… to the end of 1984-85 season Lafchis was never a regular – 27 matches for Levski-Spartak in 2 season, then 2 ’empty’ years, then 33 for OFI in 2 seasons, and 55 for Panathinaikos in 2 years. After 7 years of professional football, Lafchis achieved roughly a 50% average – certainly, a doubtful player, not a star… Greece had weaker goalkeepers than Bulgaria at the time, so the fact that he never appeared for Greece casts more doubts. And just when he seemingly came into some more reliable performance, he vanished again… after the end of 1984-85 season he was no longer part of Panathinaikos – most statistical records do not mention any club; Wikipedia places him in Belgium. A mystery again: just ‘a Belgian club’ is written, no name, no appearances… at least statistical records of the First Belgian league have no mentioning of such player. If he ever played in Belgium, it had to be in the lower divisions – clearly a step down… after playing for the top Greek club. He reappeared again in Greece – between 1987 and 1989 he played again for OFI Crete, a measly 15 matches. 30-years old he was retired from football… 130 matches in 12 years is nothing… was Lafchis just one of the countless failed players, who showed great talent at first, but quickly faded into obscurity? May be, but even this cannot be supported by evidence – very little is written about Lafchis: generally, only that he was a professional player. His current life is similar mystery.

In 1991 he reemerged in Bulgaria, now presented as a successful businessman, who became president of his original club, Levski. At the time, his appearance was welcomed with great hopes: Communism just fell down and the grip of the Communist party over football as well. Levski restored its original name and Lafchis was seen clearly as a new and sound beginning of proper professional era: coming from the West, rich, experienced, and loyal to the club he started with as a kid, certainly a fan. He was to introduce ‘normal’ business practices in the club and guide it to greatness… Big hopes, and naivete, for football clubs are never run like ‘normal’ business… and it was soon clear: was Lafchis a president or an owner? It was said ‘authoritatively’ that when he finished his money, he got rid of the club. It was said that he sold a whole team just to cover personal losses… that he sold the club to the next owner, who was no longer even called president. But the information is scarce: Lafchis was at the helm of Levski for 8 years – as a whole, successful period. Very quickly Lafchis got the best coaches and players of Bulgaria and they were winning. With time, controversies popped up – he was accused of looking after his own profit and manipulates officials. Then he was accused of ruining the club by going personally broke… Nothing is really established – pros and cons are largely journalistic and opinions. Fans, both of Levski and rival clubs, add folklore.

Thomas Lafchis as Persident of Levski (Sofia). Perhaps the moment remaining most vividly in memory is his refusal to play a Cup final against CSKA in 1996. The boycott of the Bulgarian League Cup final is remembered just because it was a scandal. Lafchis wanted foreign referees – he accused the appointed one of manipulating matches in favour of CSKA. It was a big accusation implicating everybody in Bulgarian football in massive corruption. But it was not very convincing argument – first, it was nothing new, and second, Lafchis himself was accused on numerous occasions of scheming and manipulating . Not even Levski’s fans were entirely convinced he was doing the right thing – they were hoping for another victory over the arch-enemy, not for the opposite (CSKA was awarded victory, since Levski did not show up, and got the Cup.) Fans of CSKA argued that Lafchis thought CSKA was going to win anyway, and to save face cooked the whole ‘protest’ as an excuse. Apart from this scandal hardly anything was backed with facts about Lafchis, who was less in the news than other, much more vocal and scandalous ‘presidents’. He stepped dwon – or sold – the club in 1999 and once again vanished. It seems that he divides his time between Greece and Bulgaria, running some business, but also he is a FIFA licensed players agent (very low key, if so), but generally staying away from football. His name pops up once in while for occasional interview on football – his opinions are essentially very critical and he states that he has an opinion, but no desire to take active part. Recently he became quietly involved in the futsal championship of Bulgaria. Thus, the information about him is so small, it looks like he does not want anything to be known about him. There are just three sentences about him in Wikipedia, essentially telling that he was a football player… He was a great promise back in 1977-78, but he did not become a star. Was he just one of the many ’empty promises’, or there was something else blocking his playing career? Nobody knows… an enigma.

Thomas Lafchis as Persident of Levski (Sofia). Perhaps the moment remaining most vividly in memory is his refusal to play a Cup final against CSKA in 1996. The boycott of the Bulgarian League Cup final is remembered just because it was a scandal. Lafchis wanted foreign referees – he accused the appointed one of manipulating matches in favour of CSKA. It was a big accusation implicating everybody in Bulgarian football in massive corruption. But it was not very convincing argument – first, it was nothing new, and second, Lafchis himself was accused on numerous occasions of scheming and manipulating . Not even Levski’s fans were entirely convinced he was doing the right thing – they were hoping for another victory over the arch-enemy, not for the opposite (CSKA was awarded victory, since Levski did not show up, and got the Cup.) Fans of CSKA argued that Lafchis thought CSKA was going to win anyway, and to save face cooked the whole ‘protest’ as an excuse. Apart from this scandal hardly anything was backed with facts about Lafchis, who was less in the news than other, much more vocal and scandalous ‘presidents’. He stepped dwon – or sold – the club in 1999 and once again vanished. It seems that he divides his time between Greece and Bulgaria, running some business, but also he is a FIFA licensed players agent (very low key, if so), but generally staying away from football. His name pops up once in while for occasional interview on football – his opinions are essentially very critical and he states that he has an opinion, but no desire to take active part. Recently he became quietly involved in the futsal championship of Bulgaria. Thus, the information about him is so small, it looks like he does not want anything to be known about him. There are just three sentences about him in Wikipedia, essentially telling that he was a football player… He was a great promise back in 1977-78, but he did not become a star. Was he just one of the many ’empty promises’, or there was something else blocking his playing career? Nobody knows… an enigma.

Not exactly overwhelming winners, but still historically significant ones – OPS never won a title and they were founded in 1925. At last – a triumph. The team excelled in the preliminary stage – they lost only a match and built 3-point advantage. Since most of the mini-league did not really put an effort in the ‘championship’ stage, rightly calculating that there is nothing to play for, OPS still won 9 points – second best record at this stage. KuPS added 11, but the original lead by 3 points was still sufficient for OPS to stay on top. At the end, it was their defense which made them champions – they lost only 3 matches and allowed the least number of goals in their net.

Not exactly overwhelming winners, but still historically significant ones – OPS never won a title and they were founded in 1925. At last – a triumph. The team excelled in the preliminary stage – they lost only a match and built 3-point advantage. Since most of the mini-league did not really put an effort in the ‘championship’ stage, rightly calculating that there is nothing to play for, OPS still won 9 points – second best record at this stage. KuPS added 11, but the original lead by 3 points was still sufficient for OPS to stay on top. At the end, it was their defense which made them champions – they lost only 3 matches and allowed the least number of goals in their net. Champions at last: from left: Kari Soila, Pekka Parviainen, Jukka Rantanen (mv), Ari Jalasvaara (ylhäällä),Eero Rissanen, Matti Ahonen, Juhani Himanka, Seppo Pyykkö, Pertti Pääkkö, Soini Puotiniemi, and Lauri Heikkinen. In front: Seppo Vakkari

Champions at last: from left: Kari Soila, Pekka Parviainen, Jukka Rantanen (mv), Ari Jalasvaara (ylhäällä),Eero Rissanen, Matti Ahonen, Juhani Himanka, Seppo Pyykkö, Pertti Pääkkö, Soini Puotiniemi, and Lauri Heikkinen. In front: Seppo Vakkari Ilves Tampere won the Cup – a fine ending of troublesome season. Good for the ‘lynx’, they showed claws when it mattered.

Ilves Tampere won the Cup – a fine ending of troublesome season. Good for the ‘lynx’, they showed claws when it mattered.