Bundesliga. Competitive championship as ever, with dramatic finish – 2 teams with same points and goal-difference determined the winner. At the opposite end of the table – 2 outsiders, but almost half the league was preoccupied with efforts to avoid 16th place and thus the risk of relegation. However, Bundesliga lost its edge – there was no truly exciting team and apart from Bayern, no really classy and well-rounded squads. In part, the new reality was due to the changes in football development – physical , but not imaginative players were the norm, so there was higher general level of players, but few exceptional ones. In part, the strong foreign competition – most visible in the case of foreign players: by now, top talent, including German, was going to play for higher paying Italian, Spanish, and English clubs. The result was weaker and bland German teams, decline of some formidable clubs, and narrower group of classy teams – perhaps only 3 at the moment: Bayern, which maintained high level all the time, Werder, which was up and own club, but in good shape currently, and the only steadily developing club – Bayer Leverkusen.

Hannover 96 – last with 18 points. Up and down, up and down, up and down – playing in the Bundesliga meant relegation, so consistent with its own history, Hannover was relegated.

Hannover 96 – last with 18 points. Up and down, up and down, up and down – playing in the Bundesliga meant relegation, so consistent with its own history, Hannover was relegated.

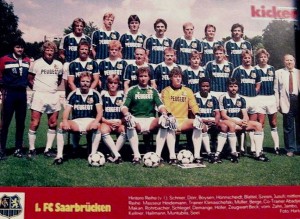

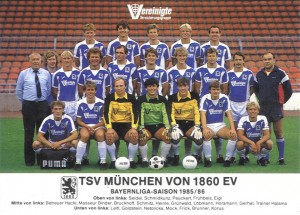

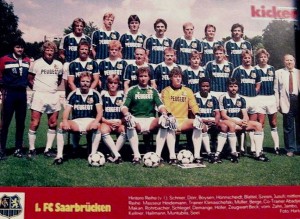

1.FC Saarbrucken – 17th with 21 points. Relegated as well and little surprise in that.

1.FC Saarbrucken – 17th with 21 points. Relegated as well and little surprise in that.

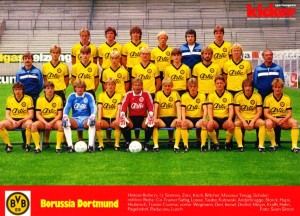

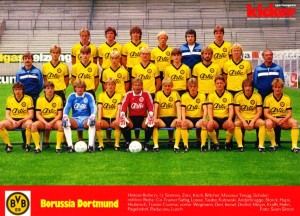

Borussia Dorlmund – 16th with 28 points. Now, this was quite a drop – just a few years back Borussia was climbing up and was one of the more promising teams. Now it looked like they were going terribly back to old ways and second0level football. And a look at the squad was telling why – Immel was the only rising star. Only two well-known players, but both getting old – Hrubesch, back from Belgium, and Raducanu, not so famous, but a Romanian national team regular for years. Yet, Borussia was not an outsider – they generally lost the fight with equal teams : the difference between them and the 8th-placed team was 5 points. And not relegated yet – they went to the promotion/relegation play-off against the 3rd team in the Second Division, Fortuna Koln, and managed to keep their place in top flight at the end.

Borussia Dorlmund – 16th with 28 points. Now, this was quite a drop – just a few years back Borussia was climbing up and was one of the more promising teams. Now it looked like they were going terribly back to old ways and second0level football. And a look at the squad was telling why – Immel was the only rising star. Only two well-known players, but both getting old – Hrubesch, back from Belgium, and Raducanu, not so famous, but a Romanian national team regular for years. Yet, Borussia was not an outsider – they generally lost the fight with equal teams : the difference between them and the 8th-placed team was 5 points. And not relegated yet – they went to the promotion/relegation play-off against the 3rd team in the Second Division, Fortuna Koln, and managed to keep their place in top flight at the end.

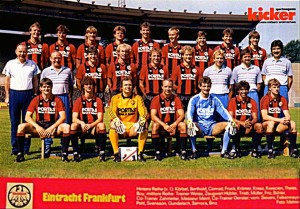

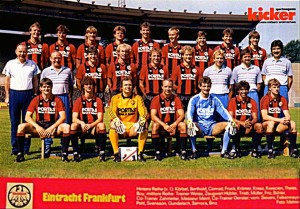

Eintracht Frankfurt lost so much ground in after 1976, that they now were among the outsiders. They survived only on better goal-difference this season, ending with 28 points like Borussia Dortmund.

Eintracht Frankfurt lost so much ground in after 1976, that they now were among the outsiders. They survived only on better goal-difference this season, ending with 28 points like Borussia Dortmund.

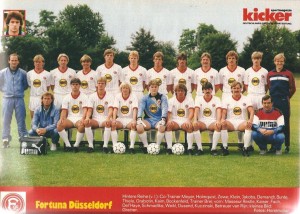

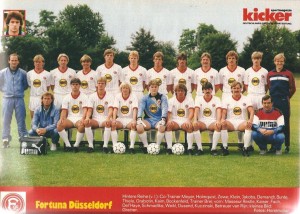

Fortuna Dusseldorf – another formerly strong club in decline. 14th with 29 points.

Fortuna Dusseldorf – another formerly strong club in decline. 14th with 29 points.

Yes, 1. FC Koln reached the UEFA Cup final, but the performance in the Bundesliga was the true story: they were going down fast. 13th with 29 points.

Yes, 1. FC Koln reached the UEFA Cup final, but the performance in the Bundesliga was the true story: they were going down fast. 13th with 29 points.

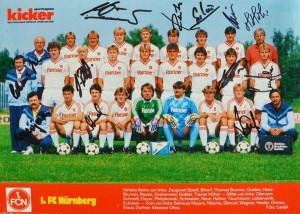

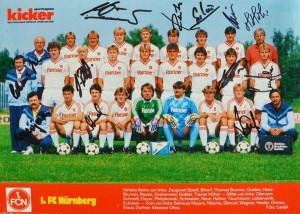

1. FC Nurnberg – familiar performance: escaping relegation equaled good season. If not relegated, they were among those barely escaping, so nothing new here – 1th with 29 points.

1. FC Nurnberg – familiar performance: escaping relegation equaled good season. If not relegated, they were among those barely escaping, so nothing new here – 1th with 29 points.

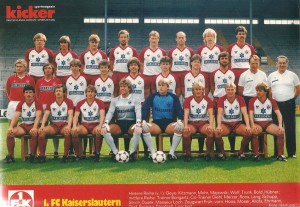

1.FC Kaiserslautern – 11th with 30 points.

1.FC Kaiserslautern – 11th with 30 points.

Schalke 04 – 10th with 30 points.

Schalke 04 – 10th with 30 points.

VfL Bochum – amazing survivors: always with a squad suggesting immediate relegation, but managing good position at the end of the season. 9th with 32 points.

VfL Bochum – amazing survivors: always with a squad suggesting immediate relegation, but managing good position at the end of the season. 9th with 32 points.

SV 07 Waldhof Mannheim – 8th with 33 points. The highest-placed team among those concerned with avoiding relegation. Well done, but more importantly was that if their squad was a bit poor, it was not very different from the squads Schalke, Koln, Dortmund, Frankfurt, and Dusseldorf had.

SV 07 Waldhof Mannheim – 8th with 33 points. The highest-placed team among those concerned with avoiding relegation. Well done, but more importantly was that if their squad was a bit poor, it was not very different from the squads Schalke, Koln, Dortmund, Frankfurt, and Dusseldorf had.

The next 4 teams were way above the lower part of the league, but not title contenders either.

Hamburger SV – 7th with 39 points. Still led by Happel, but a far cry from the team were only a few years earlier. The key stars, starting with Kaltz and Magath, were getting old and very old, but there was not single new name of great talent popping up. HSV was slowly sinking.

Hamburger SV – 7th with 39 points. Still led by Happel, but a far cry from the team were only a few years earlier. The key stars, starting with Kaltz and Magath, were getting old and very old, but there was not single new name of great talent popping up. HSV was slowly sinking.

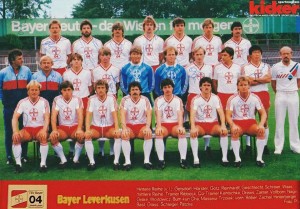

Bayer 04 Leverkusen – 6th with 40 points. Frankly, the only up and coming team at this time and that with certain doubts and cautions: yes, it was improving team and it was certain they were not one-time wonder, but it was also a team without remarkable stars. Even their foreigners – the South Korean legend Cha and the Polish national team player Wojtowicz – were second-rate. But ‘the Aspirins’ were also a prime example of the current football – a sturdy collective was a winning one and not one with few great flashy stars. Just look at 1. FC Koln and compare…

Bayer 04 Leverkusen – 6th with 40 points. Frankly, the only up and coming team at this time and that with certain doubts and cautions: yes, it was improving team and it was certain they were not one-time wonder, but it was also a team without remarkable stars. Even their foreigners – the South Korean legend Cha and the Polish national team player Wojtowicz – were second-rate. But ‘the Aspirins’ were also a prime example of the current football – a sturdy collective was a winning one and not one with few great flashy stars. Just look at 1. FC Koln and compare…

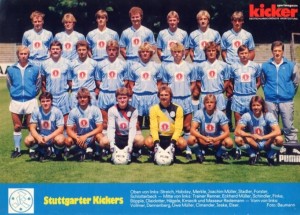

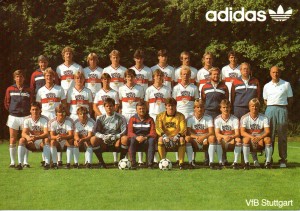

VfB Stuttgart – 5th with 41 points. Still strong, but one thing was already clear: Stuttgart did not add to the champion team they built a few years back – what they had was equal or slightly weaker than the team of very recent past. Not a title contender as a result and possibly going down in the future.

VfB Stuttgart – 5th with 41 points. Still strong, but one thing was already clear: Stuttgart did not add to the champion team they built a few years back – what they had was equal or slightly weaker than the team of very recent past. Not a title contender as a result and possibly going down in the future.

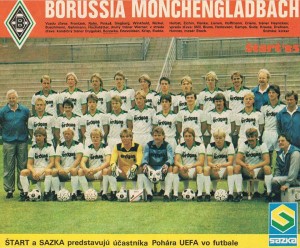

Borussia Moenchengladbach – 4th with 42 points. The strongest finisher among those much better than most of the league, but weaker than the leading teams. To see Moenchengladbach among the top teams looked both familiar a reassuring: so impressive was the great team from the 1970s, that for many this season refreshed the memories and hopes for coming back. But there was no coming back… there was no player of caliber similar to Netzer and company. Mill was perhaps the greatest player of the current squad and he was never a regular player of the national team. And it was crystal-clear that Enevoldsen and Herlovsen could be number one players of Europe or transferred to Barcelona and Real Madrid, like the imports in the 1970s Simonsen and Jensen were. May be the most accurate explanation of the good performance is Heynckes – the former great player was rapidly becoming a great coach. And he was a true child of Borussia, knowing perfectly what to do: more with little. But for how long?

Borussia Moenchengladbach – 4th with 42 points. The strongest finisher among those much better than most of the league, but weaker than the leading teams. To see Moenchengladbach among the top teams looked both familiar a reassuring: so impressive was the great team from the 1970s, that for many this season refreshed the memories and hopes for coming back. But there was no coming back… there was no player of caliber similar to Netzer and company. Mill was perhaps the greatest player of the current squad and he was never a regular player of the national team. And it was crystal-clear that Enevoldsen and Herlovsen could be number one players of Europe or transferred to Barcelona and Real Madrid, like the imports in the 1970s Simonsen and Jensen were. May be the most accurate explanation of the good performance is Heynckes – the former great player was rapidly becoming a great coach. And he was a true child of Borussia, knowing perfectly what to do: more with little. But for how long?

The top three teams competed for the title.

Bayer 05 Uerdingen – 3rd with 45 points. Their best season, the closest they came to winning a title, but having lesser team than the competition made them losing a bit of steam and ending third. Well… even at the time of collective anonymity class was prevailing. Ambition, motivation, and soldiering are rarely enough for winning. But it was great season nevertheless.

Bayer 05 Uerdingen – 3rd with 45 points. Their best season, the closest they came to winning a title, but having lesser team than the competition made them losing a bit of steam and ending third. Well… even at the time of collective anonymity class was prevailing. Ambition, motivation, and soldiering are rarely enough for winning. But it was great season nevertheless.

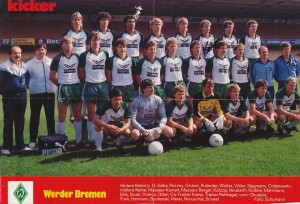

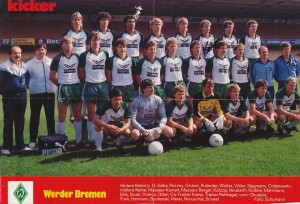

How was Werder better than Uerdingen? Well, it had higher-class players – Pezzey, Okudera, Ordenewitz, Votava, Burdenski, Sidka, Wolter, and the rapidly becoming a superstar Voller. National team players, champions with other clubs, used to both domestic and international football – that was a big difference. And having top coach was another difference – Rehhagel. Werder was up and down club, true – they even played in Second Division no long ago – but they had occasional bursts leading them to the top and this season was one of those. They run for the title and did not give up for a second – at the end, they lost the title only on goal-difference, what a misfortune. And coming to tiny details as well – compared to Bayern, Werder was older and not deep squad. That affected scoring – yes, they scored a lot, but not as much as their younger rivals. Yes, they lost only 5 games, but they won one less game than Bayern. Tiny details… and second.

How was Werder better than Uerdingen? Well, it had higher-class players – Pezzey, Okudera, Ordenewitz, Votava, Burdenski, Sidka, Wolter, and the rapidly becoming a superstar Voller. National team players, champions with other clubs, used to both domestic and international football – that was a big difference. And having top coach was another difference – Rehhagel. Werder was up and down club, true – they even played in Second Division no long ago – but they had occasional bursts leading them to the top and this season was one of those. They run for the title and did not give up for a second – at the end, they lost the title only on goal-difference, what a misfortune. And coming to tiny details as well – compared to Bayern, Werder was older and not deep squad. That affected scoring – yes, they scored a lot, but not as much as their younger rivals. Yes, they lost only 5 games, but they won one less game than Bayern. Tiny details… and second.

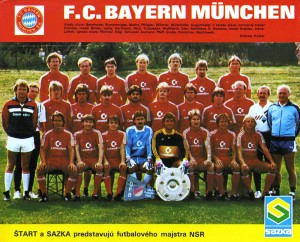

This was one of the most difficulty won titles in Bayern’s history – and, frankly, it would have been better if Werder won. But it was Bayern, so never giving up and getting victorious in any possible way. Of course, this was the strongest squad in West Germany – not very exciting and not even as strong as some older versions, but still far stronger than whatever was around. 8 West German national team players plus 1 Danish and 1 Belgian national team stars, and one unfortunate refugee – if he was not East German Junior-national team member in the past, Nachtweih would have been in the West German national team. Lattek was Lattek – a great coach always aiming at victory. Even facing tough opposition and under great pressure, at the end Bayern clinched the title.

This was one of the most difficulty won titles in Bayern’s history – and, frankly, it would have been better if Werder won. But it was Bayern, so never giving up and getting victorious in any possible way. Of course, this was the strongest squad in West Germany – not very exciting and not even as strong as some older versions, but still far stronger than whatever was around. 8 West German national team players plus 1 Danish and 1 Belgian national team stars, and one unfortunate refugee – if he was not East German Junior-national team member in the past, Nachtweih would have been in the West German national team. Lattek was Lattek – a great coach always aiming at victory. Even facing tough opposition and under great pressure, at the end Bayern clinched the title.

One more for the trophy room.

One more for the trophy room.

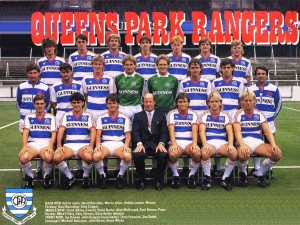

QPR had stronger squad and desperately needed trophies, but trophies are to be won and winners score goals. Let say, it was wonderful achievement reaching the final.

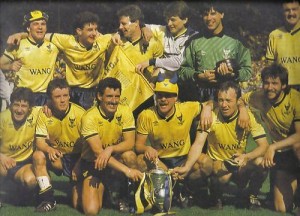

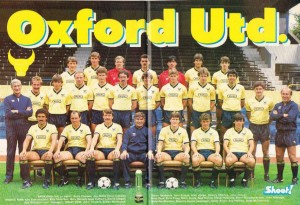

QPR had stronger squad and desperately needed trophies, but trophies are to be won and winners score goals. Let say, it was wonderful achievement reaching the final. Oxford was a pure delight – may be they did not play great football, may be they had rather anonymous squad, but victory of the underdog is always delightful. And it was very confident victory, nothing chancy – a triumph of commitment and desire.

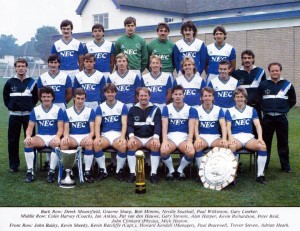

Oxford was a pure delight – may be they did not play great football, may be they had rather anonymous squad, but victory of the underdog is always delightful. And it was very confident victory, nothing chancy – a triumph of commitment and desire. Everton lost twice to Liverpool this year and finished the season emptyhanded. However, it was not that much the lost tournaments, but the perspective – what works against Everton’s myth of stunted development is the fact that Liverpool usually prevailed over this very vintage of Everton: Liverpool prevailed in the 1983-84 League Cup final, they prevailed in this final, they prevailed in the championship. That is, Liverpool was getting the upper hand against this excellent Everton’s squad. Everton was a bit weaker…

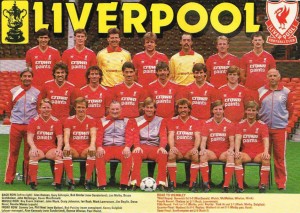

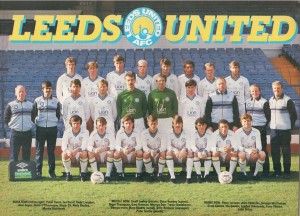

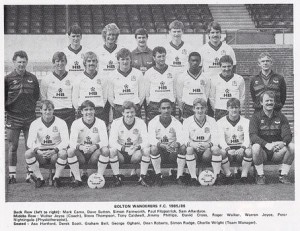

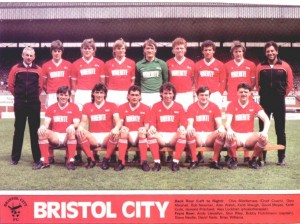

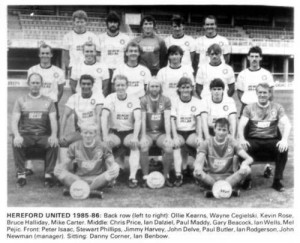

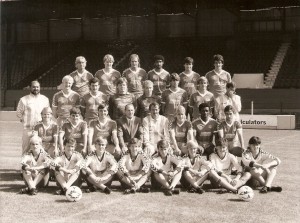

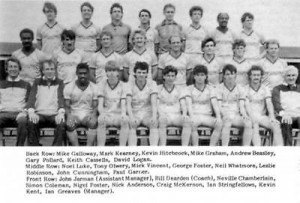

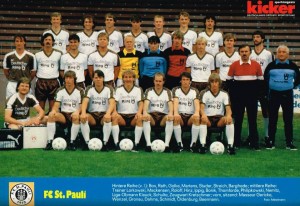

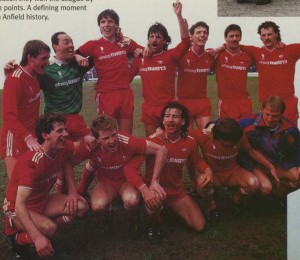

Everton lost twice to Liverpool this year and finished the season emptyhanded. However, it was not that much the lost tournaments, but the perspective – what works against Everton’s myth of stunted development is the fact that Liverpool usually prevailed over this very vintage of Everton: Liverpool prevailed in the 1983-84 League Cup final, they prevailed in this final, they prevailed in the championship. That is, Liverpool was getting the upper hand against this excellent Everton’s squad. Everton was a bit weaker… Liverpool with double this season. Beating Everton twice. Simply great. Standing from left: Kenny Dalglish, Bruce Grobelaar, Alan Hansen, Mark Lawrenson, Gary Gillespie, Ian Rush, Kevin McDonald. First row: Jim Beglin, Steve Nicol, Craig Johnston, Ronnie Whelan, Steve McMahon. It is always good to see who was sitting on the bench – otherwise the might of Liverpool could not be truly grasped. And that was the big difference between them and Everton… Liverpool was much deeper, had very strong and experienced players in the back. Even banished from European football Liverpool was not slowing down. On the other hand… it was quite boring to see Liverpool win year after year.

Liverpool with double this season. Beating Everton twice. Simply great. Standing from left: Kenny Dalglish, Bruce Grobelaar, Alan Hansen, Mark Lawrenson, Gary Gillespie, Ian Rush, Kevin McDonald. First row: Jim Beglin, Steve Nicol, Craig Johnston, Ronnie Whelan, Steve McMahon. It is always good to see who was sitting on the bench – otherwise the might of Liverpool could not be truly grasped. And that was the big difference between them and Everton… Liverpool was much deeper, had very strong and experienced players in the back. Even banished from European football Liverpool was not slowing down. On the other hand… it was quite boring to see Liverpool win year after year.