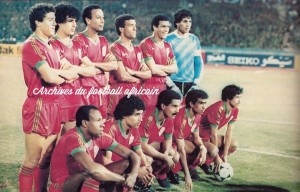

1/8 finals

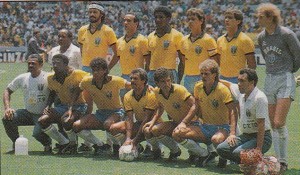

15.06.86 (12.00) Mexico City, Estadio Azteca

MEX - BUL 2:0 (1:0)

(+114000) Arppi FIlho BRA, Igna ROM, Méndez GUA

MEX: Larios - Amador, Quirarte, F.Cruz, Servin - Munoz, Negrete, Espana, Boy (c- 80 de los Cobos) - Aguirre, Sanchez

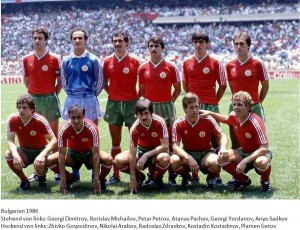

BUL: Mikhailov - Zdravkov, Arabov, Petrov, Dimitrov (c) - Sadkov, Yordanov, Kostadinov, Gospodinov - Pashev (80 Iskrenov), Getov (71 Sirakov)

1:0 Negrete 35, 2:0 Sarvin 61 h

booked: Arabov

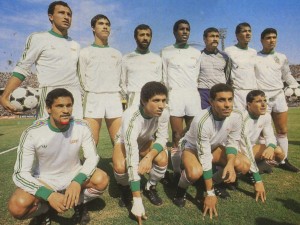

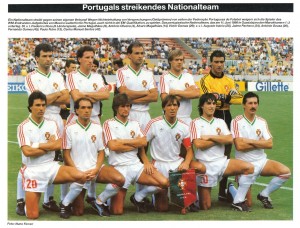

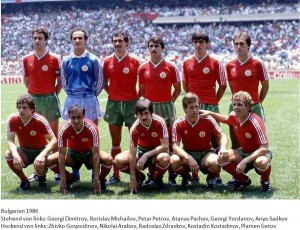

For each team the opponent was the best possible choice, but Mexico was the favourite – not only they played at home, but the Bulgarians were shapeless squad, plagued with problems, which never won a game at World Cup finals. Voutzov was paying heavy price for his own selection of players: his regulars were disappointing, he tried to change the squad and quickly run out of options. Zdravkov was moved back to play in defense, presumably, as right full-back. But that was a return to the start of the championship, the match against Italy, and the coach came back to that not because such idea worked, but because there was nobody else to try. The veteran midfielders Zhelyazkov and Plamen Markov were out, so what was left of the option played. The left winger Pashev was put in attack, combined with his club teammate Kostadinov at the other wing. Presumably, Plamen Getov was to be center-forward. It was idiotic team... the natural inclination of Bulgarian coaches for so many years was to saturate the defense, but looking at the squad it was hard to imagine how: not a team for 3-5-2 (although just by the typical positions of the players that was the concept on paper), not 4-4-2, for there were 3 strikers... not 4-3-3, not 3-4-3... what exactly was Bulgaria fielding was probably a huge mystery to the very coach making the team: there were no less than 3 attacking midfielders, playing on the left side, and quite useless anywhere else. No defensive midfielder at all, unless Zdravkov was to man this position – leaving the right flank of defense unmanned, of course. Two wingers, both restricted to his won side and unable to play at the other, but no center-forward. To some observers, it looked like that Kostadinov was moved back to midfield – 4-4-2 formation – which, if it was the grand idea, was more than stupid: the winger never played midfield in his life. The fantastic formation was entirely clueless and shapeless on the pitch – reaching new low. Mexico had no problems with its starters and was quick to explore the many weaknesses of Bulgaria, the biggest one obvious from the beginning of the game: the Bulgarian squad not only had no idea what to do on the field, but seemingly had no desire even to move. No wonder Mexico immediately occupied the Bulgarian half and not only stayed there, but created plenty of scoring opportunities. Mikhaylov, however, was rock solid and made some fantastic saves. But the goalkeeper could not resist Mexico alone and the moment when he was powerless came – incredibly beautiful shot by Negrete ended in the net. The second half started pretty much as the first half and Mexico scored a second goal – the job was more or less done, for Bulgaria clearly was powerless. The second Mexican goal curiously spurred some life in the Bulgarians and they went into attacks, but they were chaotic, just a desperate running ahead by everybody. Mexico faced some troubles, but Larios was solid between the goalposts, the Bulgarian storm was neutralized and as the game was coming near the end, the original disposition was restored – Mexico dominating, the ball in the Bulgarian half, and at least one opportunity to score a third goal. Voutzov, true to his lack of meaningful ideas made changes – what he wanted to achieve perhaps he never knew: the substitutes came too late to make any difference, they were both strikers, but they replaced strikers – if the coach wanted to put more attackers in hope of launching relentless attacks to the end, that was not the right move – he did not increase the number of attackers, it looked like making substitutions just because one can make substitutions. No miracle happened, of course, and Mexico won confidently, playing their best match so far.

For each team the opponent was the best possible choice, but Mexico was the favourite – not only they played at home, but the Bulgarians were shapeless squad, plagued with problems, which never won a game at World Cup finals. Voutzov was paying heavy price for his own selection of players: his regulars were disappointing, he tried to change the squad and quickly run out of options. Zdravkov was moved back to play in defense, presumably, as right full-back. But that was a return to the start of the championship, the match against Italy, and the coach came back to that not because such idea worked, but because there was nobody else to try. The veteran midfielders Zhelyazkov and Plamen Markov were out, so what was left of the option played. The left winger Pashev was put in attack, combined with his club teammate Kostadinov at the other wing. Presumably, Plamen Getov was to be center-forward. It was idiotic team... the natural inclination of Bulgarian coaches for so many years was to saturate the defense, but looking at the squad it was hard to imagine how: not a team for 3-5-2 (although just by the typical positions of the players that was the concept on paper), not 4-4-2, for there were 3 strikers... not 4-3-3, not 3-4-3... what exactly was Bulgaria fielding was probably a huge mystery to the very coach making the team: there were no less than 3 attacking midfielders, playing on the left side, and quite useless anywhere else. No defensive midfielder at all, unless Zdravkov was to man this position – leaving the right flank of defense unmanned, of course. Two wingers, both restricted to his won side and unable to play at the other, but no center-forward. To some observers, it looked like that Kostadinov was moved back to midfield – 4-4-2 formation – which, if it was the grand idea, was more than stupid: the winger never played midfield in his life. The fantastic formation was entirely clueless and shapeless on the pitch – reaching new low. Mexico had no problems with its starters and was quick to explore the many weaknesses of Bulgaria, the biggest one obvious from the beginning of the game: the Bulgarian squad not only had no idea what to do on the field, but seemingly had no desire even to move. No wonder Mexico immediately occupied the Bulgarian half and not only stayed there, but created plenty of scoring opportunities. Mikhaylov, however, was rock solid and made some fantastic saves. But the goalkeeper could not resist Mexico alone and the moment when he was powerless came – incredibly beautiful shot by Negrete ended in the net. The second half started pretty much as the first half and Mexico scored a second goal – the job was more or less done, for Bulgaria clearly was powerless. The second Mexican goal curiously spurred some life in the Bulgarians and they went into attacks, but they were chaotic, just a desperate running ahead by everybody. Mexico faced some troubles, but Larios was solid between the goalposts, the Bulgarian storm was neutralized and as the game was coming near the end, the original disposition was restored – Mexico dominating, the ball in the Bulgarian half, and at least one opportunity to score a third goal. Voutzov, true to his lack of meaningful ideas made changes – what he wanted to achieve perhaps he never knew: the substitutes came too late to make any difference, they were both strikers, but they replaced strikers – if the coach wanted to put more attackers in hope of launching relentless attacks to the end, that was not the right move – he did not increase the number of attackers, it looked like making substitutions just because one can make substitutions. No miracle happened, of course, and Mexico won confidently, playing their best match so far.

Bulgaria was eliminated, all too late really. Their performance had peculiar quality: they made no impression whatsoever, left no memories at all. They were going from bad to worse, every next match sinking lower. The only thing to distinguish Bulgaria was an anti-record: this was their 5th World Cup and they never won a match! The only player who played well and with heart was the goalkeeper Borislav Mikhaylov, but even his performance was not really noticed, buried in the general blank the team left after itself. Good or bad, Mikhaylov alone could not do much... Back in Bulgaria criticism was quick to come, but the venom was also misplaced: coach and players were blamed for everything and as long as they accepted that and did not talk back, everything was fine – and ready to be repeated again, for there was little real analysis and meaningful propositions for changes. It is even pointless to go into critical details of what was wrong with the selection and the tactics (if there were any, but with selection like this – what tactics?) It is pointless to ask why Christo Kolev did not play at all – perhaps the most creative midfield conductor in the squad. Actually, such stupid question surfaced at the time and it was answered that Kolev was too young and inexperienced... so, why he was hauled to Mexico than? Questions like that, leading nowhere, for they had to be asked before the World Cup. Now... Bozhidar Iskrenov practically summed the general idiocy in late in night radio interview right after the match with Mexico, which, fortunately, not many heard in 3 a.m.: 'Well, the Mexican crowd was too noisy and confused us, we are not used to play in such conditions.' Iskrenov blamed the Mexican fans... a professional player found it wrong, even malicious, to play in front of full stadium. And to confirm that no lessons were learned, that nothing will change, Georgy Dimitrov immediately after the World Cup joined the French St.Etienne in violation of the transfer rules: he was not 28 years old yet to be permitted to play abroad, but the very Federation, which made the age rule and conducted all foreign transfers simply went for the money, rule or no rule. How anything would change in such environment? The criticism was just a white noise and the general public took it exactly as that. How to take seriously criticism, when it meant nothing – Georgy Dimitrov, for instance, was chosen as one of the guiltiest, one of the prime culprits, and the piles of blame lead only to quick lucrative foreign transfer. As if he was rewarded for accepting the blame, right or wrong, going through the motions of some absurd theater.

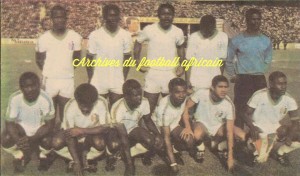

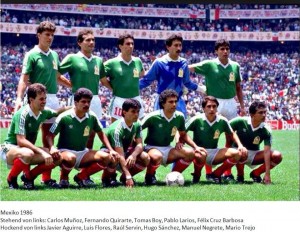

15.06.86 (16.00) Leon, Estadio Sergio Leon

BEL - ZSR 4:3 (0:1, 2:2, 3:2)

(+32000) Fredriksson SWE, Socha USA, Sánchez ESP

BEL: Pfaff - Grun (112 Clijsters), Gerets (101 L.van der Elst), Renquin, Vervoort - Scifo, Demol, Ceulemans (c), Vercauteren - Claesen, Veyt

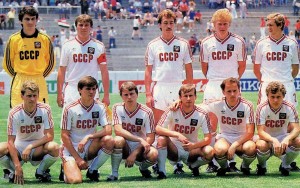

ZSR: Dassajev - Bessonov, Demianenko (c), Kuznetsov, Bal - Zavarov (73 Rodionov), Aleinikov, Yakovenko (80 Yevtushenko), Yaremchuk - Belanov, Rats

0:1 Belanov 28, 1:1 Scifo 56, 1:2 Belanov 70, 2:2 Ceulemans 78, 3:2 Demol

102 h, 4:2 Claesen 109, 4:3 Belanov 111 p

booked: Renquin

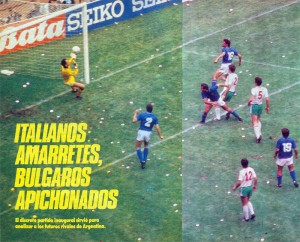

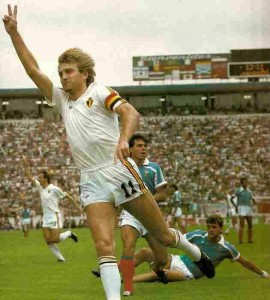

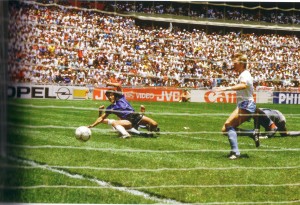

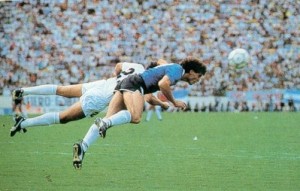

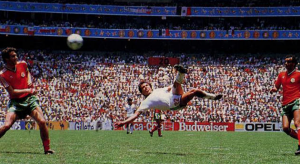

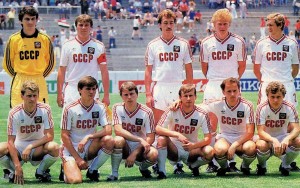

Perhaps this picture summarizes the clash between Belgium and USSR best: Dassaev desperately trying to get the ball from Claessen and meantime Kuzhetzov looks like impartial observer. One of the most memorable games in this World Cup, a long epic, which ended only after overtime, 7 goals scored, a mega-surprise – this match had everything what football fans want and cherish. This is also a bit of a controversial game: the referee was criticized and particularly in the former USSR he was and is blamed for the surprising loss – it is practically established as fact, that 2 Belgians goals were scored from offside. But careful watching of the match on cool head does not support the 'fact' and outside USSR not everybody saw referee's mistakes or at least not as the prime and only reasons for the Soviet loss. What everybody saw, however, was one huge upset of expectations: USSR was major favourite before the game, many were already certain that this team will go all the way to the final and may be even win the championship. USSR was perhaps the only team entirely praised during the group stage. Belgium, on the other hand, has been not impressive at all – sturdy and surely going to fight, but not the same team so loved in 1980. The Soviets were flying and Belgium had little to offer against such brilliant team – that was the universal opinion before the game. Perhaps the only person who was not blinded by the dazzling Soviet football was Guy Thys: he saw the weaknesses in defense and had players who were more than capable of following his instructions: it became obvious as soon as the match started. The duo in the center of the line was unstable and often left gaps, both full backs were improvised – if universal Bessonov had no problem playing right full back and did it often in the past, Bal was playing new and foreign position for him at the other side. Belgium effectively explored that. USSR also had problems in attack, where only Belanov was really dangerous striker – Zavarov was rathre attacking midfielder than pure striker, but there was practically nobody else of high class at hand. Blokhin was 34... not the player he was 10 years ago and tending to go back in midfield now. What USSR had in abundance was midfielders and Lobanovksy tried to use them to fill the gaps. But it was not major worry – it was expected that USSR will attack and Belgium will be preoccupied with defense. The Belgian approach was well known – strong defense and counterattacks, which were expected to be killed by speedy and numerous Soviet midfield. And the game started as expected – the Soviets were the stronger and more dangerous team. Only Belgium was exactly just fighting back, but organized dangerous and perhaps better tailored attacks of their own – twice they were close to scoring, the ball bouncing off the goalposts. Yet, the inevitable happened – the Soviets scored first, they were seemingly the stronger team and the first half finished 1-0. Now it looked like that the match was certainly entertaining, but USSR was still the sure winner, perhaps scoring a goal or two in the second half. Which they did, but the Belgians scored first, equalizing in the 56th minute. The Soviets did not look upset – if it was an offside, their reaction was strange: no protests. By now the weaknesses of the Soviet defensive line were already seen, but there was still no doubt they were the stronger team and going again into attack, they got the lead again in the 70th minute. And again Belgium equalized, using the gaps in the Soviet defense – and again the goal was considered unmarked offside, but the Soviet players did not protest. Regular time ended 2-2. Still USSR was favoured, this 2-2 looked somewhat strange and very likely the last Belgium could do. The extra-time was different – both teams were tired, but had no time for clever patient play, they rushed into attacks, which were also full of mistakes, providing opportunities for both teams. In the extra time team USSR started losing coherence – the simpler Belgian approach was perhaps easier to maintain, they were getting more dangerous as a result. And now they started scoring, making the result 4-2. The 4th goal was a clear evidence of the problems of the Soviet defense – it was atrocious collective mistake, nobody was in place, nobody paid attention, nobody covered the opposite players. The Soviets almost came back right away – they got a rather suspect penalty and made the result 4-3. When the referee ended the match, perhaps everybody was speechless – so much thrills and entirely unexpected winner. USSR was out... Belgium played great.

Perhaps this picture summarizes the clash between Belgium and USSR best: Dassaev desperately trying to get the ball from Claessen and meantime Kuzhetzov looks like impartial observer. One of the most memorable games in this World Cup, a long epic, which ended only after overtime, 7 goals scored, a mega-surprise – this match had everything what football fans want and cherish. This is also a bit of a controversial game: the referee was criticized and particularly in the former USSR he was and is blamed for the surprising loss – it is practically established as fact, that 2 Belgians goals were scored from offside. But careful watching of the match on cool head does not support the 'fact' and outside USSR not everybody saw referee's mistakes or at least not as the prime and only reasons for the Soviet loss. What everybody saw, however, was one huge upset of expectations: USSR was major favourite before the game, many were already certain that this team will go all the way to the final and may be even win the championship. USSR was perhaps the only team entirely praised during the group stage. Belgium, on the other hand, has been not impressive at all – sturdy and surely going to fight, but not the same team so loved in 1980. The Soviets were flying and Belgium had little to offer against such brilliant team – that was the universal opinion before the game. Perhaps the only person who was not blinded by the dazzling Soviet football was Guy Thys: he saw the weaknesses in defense and had players who were more than capable of following his instructions: it became obvious as soon as the match started. The duo in the center of the line was unstable and often left gaps, both full backs were improvised – if universal Bessonov had no problem playing right full back and did it often in the past, Bal was playing new and foreign position for him at the other side. Belgium effectively explored that. USSR also had problems in attack, where only Belanov was really dangerous striker – Zavarov was rathre attacking midfielder than pure striker, but there was practically nobody else of high class at hand. Blokhin was 34... not the player he was 10 years ago and tending to go back in midfield now. What USSR had in abundance was midfielders and Lobanovksy tried to use them to fill the gaps. But it was not major worry – it was expected that USSR will attack and Belgium will be preoccupied with defense. The Belgian approach was well known – strong defense and counterattacks, which were expected to be killed by speedy and numerous Soviet midfield. And the game started as expected – the Soviets were the stronger and more dangerous team. Only Belgium was exactly just fighting back, but organized dangerous and perhaps better tailored attacks of their own – twice they were close to scoring, the ball bouncing off the goalposts. Yet, the inevitable happened – the Soviets scored first, they were seemingly the stronger team and the first half finished 1-0. Now it looked like that the match was certainly entertaining, but USSR was still the sure winner, perhaps scoring a goal or two in the second half. Which they did, but the Belgians scored first, equalizing in the 56th minute. The Soviets did not look upset – if it was an offside, their reaction was strange: no protests. By now the weaknesses of the Soviet defensive line were already seen, but there was still no doubt they were the stronger team and going again into attack, they got the lead again in the 70th minute. And again Belgium equalized, using the gaps in the Soviet defense – and again the goal was considered unmarked offside, but the Soviet players did not protest. Regular time ended 2-2. Still USSR was favoured, this 2-2 looked somewhat strange and very likely the last Belgium could do. The extra-time was different – both teams were tired, but had no time for clever patient play, they rushed into attacks, which were also full of mistakes, providing opportunities for both teams. In the extra time team USSR started losing coherence – the simpler Belgian approach was perhaps easier to maintain, they were getting more dangerous as a result. And now they started scoring, making the result 4-2. The 4th goal was a clear evidence of the problems of the Soviet defense – it was atrocious collective mistake, nobody was in place, nobody paid attention, nobody covered the opposite players. The Soviets almost came back right away – they got a rather suspect penalty and made the result 4-3. When the referee ended the match, perhaps everybody was speechless – so much thrills and entirely unexpected winner. USSR was out... Belgium played great.

Instead of winning the title, USSR went home early – a sensational shock. Back at home, the failure was blamed first on the referee, and, second, on Lobanovsky. His decision to use substitutes against Canada was considered wrong and fatal – the flow of the team was broken. This argument is hard to judge: Lobanovsky broke long Soviet tradition to use regulars no matter what opponent, but there were plenty of examples when second teams were used in meaningless games to give a break to the regulars. The Mexican conditions – the heat and many complains about difficult surface of the stadiums – support Lobanovsky's decision. Lack of spirit was not the problem against Belgium, nor was sudden drop of form – the problems of Soviet defense had nothing to do with that, they were quite objective and old. Lobanovsky had to improvise defensive line every match: the best Soviet central defenders were injured and not in the team at all. There was problem with right full backs: no good ones in the country. The defense was shaky and beatable, especially by clever team like Belgium, tactically well versed and able to use weaknesses. Finally, the attack suffered from the same problem – few really good players, limited options. Belgium suffered from similar problems, but coped much better because of different tradition and approach: it was a team traditionally oriented towards defensive play and building counterattacks from its defensive line – so, all Belgian defenders were skilled in using the offside trap and and starting counterattacks. It worked perfectly against attack-oriented team, which built its game in midfield. May be the big mistake of Lobanovsky was leaving Protassov on the bench, but it is academic argument: Protassov was new and inexperienced player yet. The usual arguments against Lobanovsky – ignoring Spartak (Moscow) players in favour of his own Dinamo (Kiev) players does not hold water this time: apart from Dassaev, Spartak had nothing else to offer, as far as the weak positions are concerned. The elimination of USSR was seen as a big upset only because big expectations were built on very weak foundation: the group phase of the World Cup was bland and USSR suddenly was the bright light with its huge win over Hungary. After that the Soviets were not so 'great' and the tougher the opponent, the more difficult was for them – until they met a team determined to play to the last minute and sophisticated enough to see and use the obvious weaknesses of USSR. A team, which could not be outrun, a team very skillful in defense and having inconvenient tactics. USSR did not fail from grace – it played to the best of its ability and was outplayed just a little.

16.06.86 (12.00) Guadalajara, Estadio Jalisco

BRA - POL 4:0 (1:0)

(~45000) Roth GER, Márquez MEX, Snoddy NIR

BRA: Carlos - Josimar, Julio Cesar, Edinho (c), Branco - Elzo, Alemão, Socrates (70 Zico), Junior, Careca, Müller (74 Silas)

POL: Młynarczyk - Przybyś (60 Furtok), Ostrowski, Tarasiewicz, Karaś - Wójcicki, Majewski, Urban (84 Żmuda), Boniek - Dziekanowski, Smolarek

1:0 Socrates 30 p, 2:0 Josimar 54, 3:0 Edinho 78, 4:0 Careca 82 p

booked: Careca, Edinho / Boniek, Smolarek, Dziekanowski

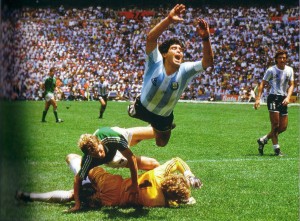

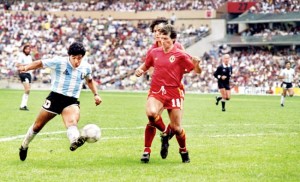

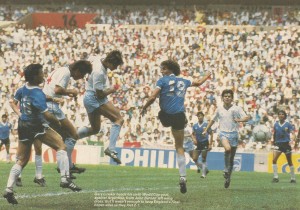

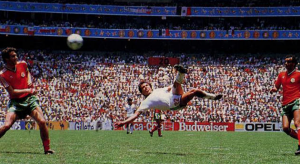

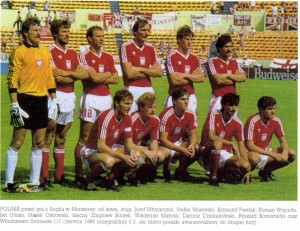

Well, another picture which tells it all. After the match many observed that both teams played as if continuing their previous games: Brazil was flying and Poland losing ground by the minute and with that, losing even desire to play, reaching eventually a state of indifference. Brazil was going up and up, now it looked like they were coming back to the excellent form they had in Spain'82, playing with joy and inspiration. The teams also looked finally shaped, everything was fine. As for Poland, the low expectations of them were entirely fulfilled: they were not a great team. Frankly, the only plausible thing to say about the Polish performance in Mexico was the gentlemanly decision to make Zmuda real 4-time World Cup player: it was not enough to be in the squad for that, one had to play a bit and he was fielded late in the clearly lost match against Brazil to make this crucial appearance. A honorable decision, but that was everything to say about Poland – it was clueless team from start to finish and in this match it became clear in the first minutes that Brazil will win. It was only a matter of time and the only question was how many goal the Brazilians will score. They scored 3 and the rise of Josimar continued, for not only he had a great day again, but scored again a goal – his second match for the national team and he scored 2 goals. That a right full back! The Brazilian magic was found again, may be even better magic than 4 years ago: good goalkeeper, solid defense, bright midfield, good attack. The problem of age also was seemingly solved: start with Socrates, then replace him when he gets tired with Zico. There was very little to say against this team and against Santana now, even in Brazil: the team won every game it played, received 0 goals, scored 6 in its last two games. They were playing beautifully again, started to score a lot, and were very strong in defense as well. New stars were rapidly rising too – all Brazil was loved for was in place, this was prime candidate for the title.

Poland said good bye to Mexico too late for some. 1978 was repeated, just as some observers warned before the finals – after the great jump up, big fall down. It was not a great squad and there was nothing to be done about it: it was objective problem of not having enough talent at the moment. Basically, the team depended on the due Boniek-Smolarek, who were getting long in the tooth both individually and as a combination. It was useful to recall that this was the 3rd World Cup for Boniek – he was neither young, nor a surprise anymore. His inevitable decline was already noticed. But if Boniek was the young broom, the only bright player of tired and quite shapeless team in 1978, now there was no new emerging talent. Objectively, Poland had to be satisfied with reaching the World Cup and nothing more. The only thing to blame them was the lack of desire to play – they were quite indifferent. Not that much easily discouraged, but indifferent. No motivation at all. For such a team and for such an attitude, they progressed too far in the championship.

16.06.86 (16.00) Puebla, Estadio Cuauhtemoc

ARG - URU 1:0 (0:0)

(~26000) Agnolin ITA, Valente POR, Courtney ENG

ARG: Pumpido - Cuciuffo, Ruggeri, Brown, Garré - Giusti, Batista (87 Olarticoechea), Burruchaga, Pasculli - Maradona (c), Valdano

URU: Alvez - Gutierrez, Acevedo (61 Paz), Rivero, Santin - Ramos, Bossio,Barrios (c), Pereyra - Cabrera (46 da Silva), Francescoli

1:0 Pasculli 42

booked: Garré, Brown, Pumpido / Francescoli, Acevedo, da Silva, Santin

NOTE: The Uruguayan coach banned from taking place on the bench.

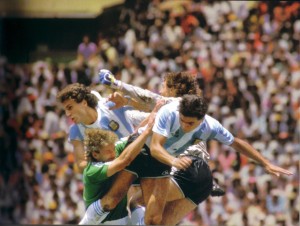

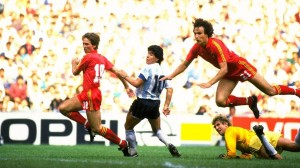

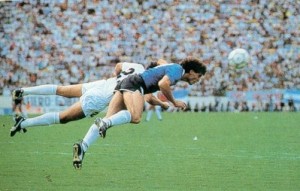

The 400th game of the World Cup

And one more photo capturing best the match. The monstrous clash of Argentina and Uruguay is a match put in the dark corner. The terrible reputation of Uruguay is the prime reason – it is enough to see the stats: 7 yellow cards! It is enough to remember the old rivalry between the two countries, which suggests lot of fights and little football – the result supports that. It is enough to recall that two teams with defensive tactics met, to 'be sure' that this game was very likely slow and riven by petty tricks. And then watch the game. Most of the expected was there, but it was fast, attack-oriented match with tons of football and thrilling moments. Neither team waited the other to make mistake, but tried its best to create scoring opportunities and score. It was clash of giants, equally vicious, but almost equally creative and determined to prevail. It is a miracle only one goal was scored and Argentina was lucky to win the game – the match easily would have ended any possible way. The TV camera often went to the stands, showing an old man calmly sipping mate – ah, can't miss the arch-devil Borras! He was a 'news'... let see what he is doing – some wild gestures, may be some voodoo ritual, fresh blood of just killed virgins? The devil just watched the game, not even reacting to some suspect calls on the pitch. Meantime his boys fought the neighbours with everything they had – and met equally tough, but creative opponents. That was the biggest surprise of this match – neither team barricaded itself in its own half, baiting the enemy to come forward and use an odd chance to counterattack. Argentina was slightly stronger and more dangerous, but Uruguay was not really weaker and there was no a moment of relaxation. Of course, the enemies kicked each other and then some more. Of course, they argued with the referee beyond the high limit of tolerance in the 80s – that was how Pumpido got booked. But despite the brutality, both teams played some fantastic football. Unlike many games of the championship, this one deserves a second watching. And it was too bad Uruguay lost, they did not deserve it really, although everybody was happy to see them out, because by now everybody was biased against them. As for Argentina – for the first time the team showed they can actually play football. After this match Argentina started to shape into title contender in the minds of observers and fans.

And one more photo capturing best the match. The monstrous clash of Argentina and Uruguay is a match put in the dark corner. The terrible reputation of Uruguay is the prime reason – it is enough to see the stats: 7 yellow cards! It is enough to remember the old rivalry between the two countries, which suggests lot of fights and little football – the result supports that. It is enough to recall that two teams with defensive tactics met, to 'be sure' that this game was very likely slow and riven by petty tricks. And then watch the game. Most of the expected was there, but it was fast, attack-oriented match with tons of football and thrilling moments. Neither team waited the other to make mistake, but tried its best to create scoring opportunities and score. It was clash of giants, equally vicious, but almost equally creative and determined to prevail. It is a miracle only one goal was scored and Argentina was lucky to win the game – the match easily would have ended any possible way. The TV camera often went to the stands, showing an old man calmly sipping mate – ah, can't miss the arch-devil Borras! He was a 'news'... let see what he is doing – some wild gestures, may be some voodoo ritual, fresh blood of just killed virgins? The devil just watched the game, not even reacting to some suspect calls on the pitch. Meantime his boys fought the neighbours with everything they had – and met equally tough, but creative opponents. That was the biggest surprise of this match – neither team barricaded itself in its own half, baiting the enemy to come forward and use an odd chance to counterattack. Argentina was slightly stronger and more dangerous, but Uruguay was not really weaker and there was no a moment of relaxation. Of course, the enemies kicked each other and then some more. Of course, they argued with the referee beyond the high limit of tolerance in the 80s – that was how Pumpido got booked. But despite the brutality, both teams played some fantastic football. Unlike many games of the championship, this one deserves a second watching. And it was too bad Uruguay lost, they did not deserve it really, although everybody was happy to see them out, because by now everybody was biased against them. As for Argentina – for the first time the team showed they can actually play football. After this match Argentina started to shape into title contender in the minds of observers and fans.

Uruguay built such ugly reputation, everybody wanted them out and it was a relief to see them gone. The reaction in Uruguay was different – opinion changed from almost hatred for Borras and his hopeless team before the World Cup started to rallying in support of coach and team wronged by the world. There was an element of which-hunting and scapegoating by now – Uruguay was labeled arch-villains, so it was easy to blame them even before they moved. Was Uruguay the most brutal team at the 1986 finals? Hardly. They were more open about it, though, and they also argued a lot with the referees, so they were easy target for collective hating. The real problems of Uruguay were different, though: the defensive tactic, professed by Borras, by itself was not wrong: Argentina used the same approach. But in the Uruguayan case, it affected the play of Francescoli – 'the Prince' was not very effective most of the time. Since Uruguay had small pool of players, it was wrong to leave some of the best out of the team – that especially true for strikers. That were the prime reasons for the early exit of Uruguay, even for the lucky reaching of the second stage of the championship. Were they capable of more? Depends... they played their best football against Argentina, so it looked like that they were more comfortable playing with South American teams. Any other opponent somehow lead Uruguay to recoil into their defensive brutality, destroying any attempts at playing football – so, it was deserved end of the line. There was no pleasure in watching butchers on one hand and on the other – Denmark annihilated the butchers entirely. One thing was sure and remains: everybody was just happy to get rid of Uruguay.

17.06.86 (12.00) Mexico City, Estadio Olimpico '68

FRA - ITA 2:0 (1:0)

(~70000) Esposito ARG, Diaz COL, Martinez URU

FRA: Bats - Ayache, Battiston, Bossis, Amoros - Giresse, Tigana, Fernandez (75 Tusseau), Platini (c - 86 Ferreri) - Rocheteau, Stopyra

ITA: Galli - Bergomi, Vierchowod, Scirea (c), Cabrini - G.Baresi (46di Gennaro), de Napoli, Bagni - Conti, Altobelli, Galderisi (58 Vialli)

1:0 Platini 16, 2:0 Stopyra 56

booked: Ayache / de Napoli, di Gennaro

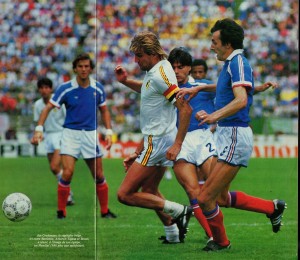

The noise around this match was great – expectations, speculations, predictions, interviews, until the start of the match. The reigning World champions against the reigning European champions, what a thrill! Neither team played well so far... but Italy started slow and only improved when really mattered, culminating at the semi-finals and the final in 1982. France started badly, but seemingly was going up every next game they played. This was the moment for some terrific display of football, then – it was all or nothing. There was lots of 'nothing' on the field, though... Italy did not improve, very likely could not improve. France was, if anything, very experienced team and managed to kill the only danger Italian attack possessed: Altobelli. The French superiority in midfield decided the match: Altobelli was cut of from supply, the Italian defense was perhaps lured a bit closer to the center of the field, because the main actions was going on in midfield and if you want to get the ball from Platini and company, you have to go near them, thus leaving gaps and empty spaces near your own net. France cleverly capitalized on that – their strikers, as ever, were not the greatest danger, but they kept defenders' attention on themselves and speedy midfielders popped up dangerously from behind. Since France was not just Platini, keeping an eye on him was more confusing than anything else – when Italians paid him attention, the action simply moved to some other place, unwatched at the moment. Largely, Italy lost the midfield and with that – the match. It was fair result.

The noise around this match was great – expectations, speculations, predictions, interviews, until the start of the match. The reigning World champions against the reigning European champions, what a thrill! Neither team played well so far... but Italy started slow and only improved when really mattered, culminating at the semi-finals and the final in 1982. France started badly, but seemingly was going up every next game they played. This was the moment for some terrific display of football, then – it was all or nothing. There was lots of 'nothing' on the field, though... Italy did not improve, very likely could not improve. France was, if anything, very experienced team and managed to kill the only danger Italian attack possessed: Altobelli. The French superiority in midfield decided the match: Altobelli was cut of from supply, the Italian defense was perhaps lured a bit closer to the center of the field, because the main actions was going on in midfield and if you want to get the ball from Platini and company, you have to go near them, thus leaving gaps and empty spaces near your own net. France cleverly capitalized on that – their strikers, as ever, were not the greatest danger, but they kept defenders' attention on themselves and speedy midfielders popped up dangerously from behind. Since France was not just Platini, keeping an eye on him was more confusing than anything else – when Italians paid him attention, the action simply moved to some other place, unwatched at the moment. Largely, Italy lost the midfield and with that – the match. It was fair result.

Italy deserved to lose and go home. The hopes that Italy will get stronger with time did not materialized, the team struggled with some uninspired and boring football from start to elimination. And it was clear why they went home early: not enough good players. The heroes of 1982 were no longer around or they aged and were pale shadows of their former selves: Rossi did not appear at all. As a general impression, this squad was composition of leftovers from 1982, mostly players, who were reserves back then, and various second stringers, who would not make the squad 4 years earlier. There was new talent, but at the moment too young to put in central position: thus, Conti (31 years old and not really great anymore) and Altobelli (30 years old) were the key attackers. Vialli (21) and Galderisi (23) were substitutes. Italy was shaky team caught between generations – the old guard was going out, the young talent was still not fully bloomed. Frankly, Italy deserved to go home and if not for the weak group they were in the opening stage, most likely they would have gone home earlier.

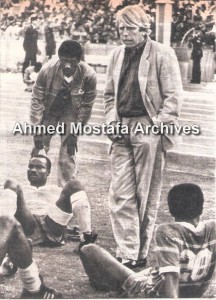

17.06.86 (16.00) Monterrey, Estadio Universitario

GER - MAR 1:0 (0:0)

(-19000) Petrović JUG, Brunmeier AUT, Nemeth HUN

GER: Schumacher - Berthold, K.-H.Förster, Jakobs, Briegel – Eder, Matthäus, Magath, Rummenigge (c) - K.Allofs, Völler (46 Littbarski)

MAR: Zaki (c) - Khalifa, Bouyahyaoui, Oudani, Lemriss - Dolmy, El Haddaoui, Bouderbala, Timoumi - Khairi, Krimau

1:0 Matthäus 89 f

booked: Lemriss, Khalifi

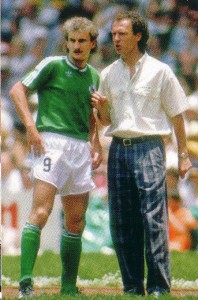

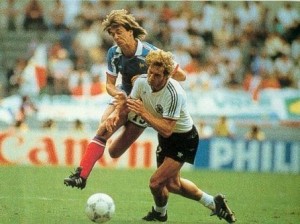

If we take this moment... wow, what a match! Deceiving photo. Of course, West Germany was the big favourite here – yes, the Germans played terribly so far, but they made it by sheer will and determination, and Morocco was the easiest possible opponent. Yes, it was clear that the Germans will not play some interesting football, but it was expected that Morocco exhausted its strength in the group stage and will be easy target for physically superior team with iron will. What happened on the field was both expected and unexpected. The weather was very hot and the match proceeded in slow tempo – however, it looked deliberate. Later, many had the impression that Morocco did not play to win, it was disinterested team. But a close look at game suggests different view: looks like Faria tried to find tactic giving his boys a chance. Hot or cold, West Germany preferred high speeds, constant running, constant pressing, constant battle, so its physical superiority to win the game. Morocco, more skillful team, played slow and mostly in the middle zone. Thus, its technical superiority gave them control of the ball and thus of the tempo. The West Germans were never comfortable when the tempo was sluggish, they could not get the ball and were also lulled by the slow ball moving somewhere near the central line. As soon as the Moroccans saw the opposition going to sleep, there was lightning long pass deep in the German half, most often in some relatively empty space, giving a good chance for a speedy striker to go alone right to Schumacher. With difficulty, the German defenders managed to kill all such dangers, using offside trap, but the Moroccans patiently tried again. This was clever tactic, the best possible against West Germany, it taxed German defense pretty much to the maximum. Too bad Morocco did not score – for West Germany had no answer really. The Germans were especially hopeless in attack, could not built anything even barely meaningful, and lost the midfield entirely as well. But they did not allow a Moroccan goal, and that was the decisive factor. Just before the final whistle, when it was damn sure the match was going into extra-time, the Germans scored. Out of nothing... from a free kick. It was sheer luck – true, Matthaus kicked a good ball, but Moroccan defenders and goalie made collective mistake when building the wall. German luck, which of course, was not just luck – the Germans, good, bad, or ugly, were very sophisticated players with nerves of steel. Playing to the last second, trying any opportunity, no matter how hopeless. Never giving up, never losing their cool, just like machines. In a long run, machines win. No pleasure in watching machines, though...

Morocco was eliminated, but they went home satisfied. Went farther than any African team before. Played quite well. Won their group. Above expectations, even their own. Jose Faria did splendid job with his selection, especially in the tactical aspects. Tactics were always the weak side of African teams , but this time the problem was seemingly solved: Faria taught his players not only what he wanted from them to do, but actually to do it on the field. The playmaking abilities of Mohamed Timoumi were put to great use and effect. Losing to West Germany was no shame – Morocco practically outplayed the opposition. Unfortunately, to break the Germans was not easy, so Morocco was unable to score. As for the goal which decided the match – well, Germans... they prevailed against bigger, stronger, scarier teams than Morocco just the same way. One moment was enough to lose a game against West Germany. Too bad Morocco was eliminated, though – they were much better fun than the iron toys. Yet, it was great for the whole African football Morocco went that far and left very good impressions.

18.06.86 (12.00) Mexico City, Estadio Azteca

ENG - PAR 3:0 (1:0)

(-99000) Al-Sharif SYR, Al-Shanar ARS, Ponnet BEL

ENG: Shilton (c) - G.M.Stevens, Martin, Butcher, Sansom - Steven, Reid (58 G.A.Stevens), Hoddle, Hodge - Lineker, Beardsley (82 Hateley)

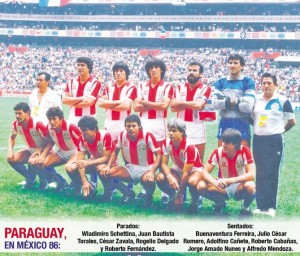

PAR: Fernandez - Torales (85 Guasch), Schettina, Delgado (c), Zabala – Canete, Romero, Nunez, Ferreira - Cabañas, Mendoza

1:0 Lineker 32, 2:0 Beardsley 56, 3:0 Lineker 72

booked: Martin, Hodges / Romero, Nunez

NOTE: The Paraguayan coach banned from taking place on the bench

Before the game Bobby Robson said his England will win 3-0. His arguments were met with strong skepticism – England did not play well so far and its defense was dangerously outdated, playing in line. However, it was pretty much clear how the opponents will play: Paraguay depending on solid defense and the speed of Romero and Cabanas in counterattacks. England – attacking relentlessly and trying to prevent long passes to the deadly Paragayan duo in front. Neither team had anything else to offer... What was somewhat left unvoiced – because Uruguay was the greatest villain, taking all attention and blame on itself – was that most likely this match will be tough and brutal. Paraguay had long tradition of playing dirty; England never shied away from bruising tackles either. Depends on how one views the game of football, though... British commentators preferred to describe team Paraguay as 'very physical'. Anyhow, the game proved Robson right, those expecting 'manly football' right, those pointing out weaknesses before the match were also right. It was not the Uruguayan coach watching from the stands – the Paraguayan one was also suspended. 4 yellow cards were shown during the game, equally, 2 yellows each team. English defense was vulnerable and too slow for speedy Romero and Cabanas. Luckily, the ball rarely reached them. Paraguayan defense played also just as expected, however, it was tricked. Robson said – and nobody believed him – that he made some changes to surprise Paraguay. The change was long waited for: it was clear that the only lively thing in English attack was Lineker and something had to be readjusted in order of utilizing his abilities. That was to make him the pinnacle of the attack, the game to be shaped around him. A technical, speedy, mobile striker with no fixed position in front. He was more of a problem for his teammates, though – as the match progressed, it was clear that Robson asked his players to create opportunities for Lineker, to watch him and what available space he has, to use surprise openings, but hundred years old habits were difficult to break and the English often made high crosses to the front of the Paraguayan net – a tall center-forward must be there, to battle for the ball in the air and strike it in the net. But there was no tall center-forward, there was nobody now and the cross was wasted. Paraguayan defense was also more confident with air battles for balls coming from the wings, but the absence of enemy striker was nothing to complain about. Stopping Lineker was another matter – the Paraguayan apparently did not expect his kind of play and found no answer. Robson's idea were for using Lineker required a second player – Beardsley, who was similarly unfixed in one place striker. That was perhaps the best way to force English midfield out of old habits – to make them see there was nobody hulking in front of the Paraguayan goalkeeper and thus to restrain the natural desire to make a cross. And that decided the outcome of the match, fairly early too – Lineker scored and England was leading 1-0 at half time. Then early in the second time a second goal was scored and finally Lineker made it 3-0. Meantime Paraguay failed to score – opportunities were missed, but Shilton also played very solidly and more. More or less, Paraguay, with its limited resources, had no other option: no great midfielder to control ball and tempo, and to create opportunities. It was a team of soldiers, they did their best, but when it came to attacking, it was just long ball in empty space to Romero and Cabanas. English defense had no real answer to the duo – too slow – so they were to be tackled illegally as soon as possible, before they were near the net in scoring position. Luckily, England possesed the ball most of the time and gave relatively few opportunities for counterattacks, just as hoped. England did not look particularly stronger than Paraguay, but won 3-0 and more importantly showed some life and creativity. And because of that suddenly popped up as a potential title contender in the eyes of many.

Before the game Bobby Robson said his England will win 3-0. His arguments were met with strong skepticism – England did not play well so far and its defense was dangerously outdated, playing in line. However, it was pretty much clear how the opponents will play: Paraguay depending on solid defense and the speed of Romero and Cabanas in counterattacks. England – attacking relentlessly and trying to prevent long passes to the deadly Paragayan duo in front. Neither team had anything else to offer... What was somewhat left unvoiced – because Uruguay was the greatest villain, taking all attention and blame on itself – was that most likely this match will be tough and brutal. Paraguay had long tradition of playing dirty; England never shied away from bruising tackles either. Depends on how one views the game of football, though... British commentators preferred to describe team Paraguay as 'very physical'. Anyhow, the game proved Robson right, those expecting 'manly football' right, those pointing out weaknesses before the match were also right. It was not the Uruguayan coach watching from the stands – the Paraguayan one was also suspended. 4 yellow cards were shown during the game, equally, 2 yellows each team. English defense was vulnerable and too slow for speedy Romero and Cabanas. Luckily, the ball rarely reached them. Paraguayan defense played also just as expected, however, it was tricked. Robson said – and nobody believed him – that he made some changes to surprise Paraguay. The change was long waited for: it was clear that the only lively thing in English attack was Lineker and something had to be readjusted in order of utilizing his abilities. That was to make him the pinnacle of the attack, the game to be shaped around him. A technical, speedy, mobile striker with no fixed position in front. He was more of a problem for his teammates, though – as the match progressed, it was clear that Robson asked his players to create opportunities for Lineker, to watch him and what available space he has, to use surprise openings, but hundred years old habits were difficult to break and the English often made high crosses to the front of the Paraguayan net – a tall center-forward must be there, to battle for the ball in the air and strike it in the net. But there was no tall center-forward, there was nobody now and the cross was wasted. Paraguayan defense was also more confident with air battles for balls coming from the wings, but the absence of enemy striker was nothing to complain about. Stopping Lineker was another matter – the Paraguayan apparently did not expect his kind of play and found no answer. Robson's idea were for using Lineker required a second player – Beardsley, who was similarly unfixed in one place striker. That was perhaps the best way to force English midfield out of old habits – to make them see there was nobody hulking in front of the Paraguayan goalkeeper and thus to restrain the natural desire to make a cross. And that decided the outcome of the match, fairly early too – Lineker scored and England was leading 1-0 at half time. Then early in the second time a second goal was scored and finally Lineker made it 3-0. Meantime Paraguay failed to score – opportunities were missed, but Shilton also played very solidly and more. More or less, Paraguay, with its limited resources, had no other option: no great midfielder to control ball and tempo, and to create opportunities. It was a team of soldiers, they did their best, but when it came to attacking, it was just long ball in empty space to Romero and Cabanas. English defense had no real answer to the duo – too slow – so they were to be tackled illegally as soon as possible, before they were near the net in scoring position. Luckily, England possesed the ball most of the time and gave relatively few opportunities for counterattacks, just as hoped. England did not look particularly stronger than Paraguay, but won 3-0 and more importantly showed some life and creativity. And because of that suddenly popped up as a potential title contender in the eyes of many.

Let face it: nobody expected much of Paraguay. Rather anonymous squad, most likely to be just happy playing at the finals after enormously long absence, and go home after the group stage. May be some memorable effort, but no more. Romero and Cabanas were stars, no doubt about it, but having only two strikers was hardly enough even for occasional heroics. Paraguay was expected to tough to beat team, though – expected to be organized, brutal, alert, fit. Physically strong. Given all that, Paraguay did better than expected. Yet, it was obvious they could go further only if having some tremendous luck. A brave team, yet nothing special. May be the referee failed to give them a penalty against England, but even if he did... the result was already 2-0 England. Well, modest ending, but generally not bad performance. It is also good to points out that thanks to monstrous brutality on display in so many games, the Paraguayan contributions in this department paled, were 'also run' at best, practically unnoticed. One can be sorry for Romero and Cabanas, though – wonderful players, who most likely would not appear at another World Cup.

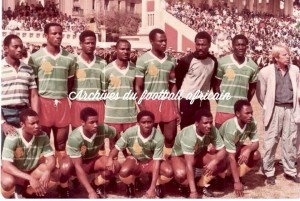

18.06.86 (16.00) Queretaro, Estadio La Corregidora

ESP - DAN 5:1 (1:1)

(~38500) Keizer HOL, Dochev BUL, Ben Naceur TUN

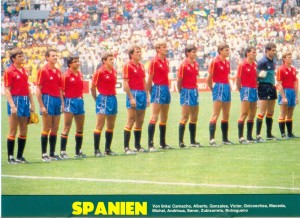

ESP: Zubizarreta - Tomás, Gallego, Goicoechea, Camacho (c) - Julio Alberto, Victor, Michel (84 Francisco), Caldere - Butragueno, Julio Salinas (46 Eloy)

DEN: Høgh - Busk, M.Olsen (c), I.Nielsen, Andersen (60 Eriksen) – Berggren, J.Olsen (71 Mølby), Bertelsen, Lerby - Laudrup, Elkjær-Larsen

0:1 J.Olsen 33 p, 1:1 Butragueno 43, 2:1 Butragueno 56 h, 3:1 Goicoechea 69 p,

4:1 Butragueno 80, 5:1 Butragueno 90 p

booked: Goichoecea, Camacho / Andersen

What makes football great? Games likes this one. Big surprise, which nobody likes, save the winners. At the group stage Denmark was the only team which not only played wonderful football, but was getting stronger in every next game. Spain... not so. The impression was that they spent more that they have in the effort to reach the 1/8 finals. Tough, difficult, but beatable – especially by flying team like Denmark. What was rubbing some observers the wrong way was the arrogant confidence of Piontek, practically boasting that his boys were not even showing all they can and thus every opponent was going to lose. No doubt about it. Looked like Piontek was losing reality, especially when the relaxed atmosphere of the Danish camp was observed closely: it was enough to see Elkjaer-Larsen sitting next to the swimming pool with cigarette in one hand and cold beer in the other. Other teams trained, the Danes lounged... And paid the price for that. And what price they paid! Spain utterly destroyed them. Yet, it did not happened right away – about 60 minutes Denmark was not only superior, but proved Piontek right – the commanded the match, the ball was mostly in the Spanish half, the victory was crystal clear... Denmark scored first and now it was just a matter of how many more goals they will put in the Spanish net. But in the 56th minute, despite the great dominance of the Danes, the result was 1-2. Terrible mistake of Morten Olsen presented Spain with equalizer just before the first half. And then a corner kick provided the second goal – the Danish defense was too slow and too heavy in the air. Meantime Denmark missed a number of great opportunities ans who does not score... the Danes went frantically ahead after the second goal and lost balance, lost any thought of defense, and that was their undoing – Spain scored 3 more goals. Yes, it was explosion, but this time the dynamite exploded in the hands of its own creators. It was unbelievable. And even more so to those, who saw the match – Denmark did not look worse, on the contrary – whoever heard the result first and watched the match later had the impression that the news got the result wrong... but it was not and it was Elkjaer-Larsen with 4 goals, but 'the Vulture'.

Many were shocked and lamented the elimination of USSR, but more so after the elimination of Denmark. After all, this was the team playing more exciting football every next game and certainly the most entertaining football so far. And they were the better team against team for the most of the time, far better... Their failure was blamed on arrogance, but there was more of course: the problems of Danish defense were noted well in advance. Old, slow, and heavy was the verdict, vulnerable line. It was true to the point – Morten Olsen was 36 years old, Busk – 33. There was objective problem – deficit of good defenders, Denmark had only 6 in the squad, and the regulars were practically irreplaceable. Mexican conditions did not help the oldest players – it was the opposite. Add to it the chronic deficit of top class goalkeepers. But all that was well known in advance, best to Piontek. The real problem was something else: Denmark was compared to the great Ajax of the early 1970s, they were called the new Ajax. Sounded great and real bright spot for many fans and specialists in the dull football of the 1980s – so great and optimistic ray of light, that something very important was obscured. Denmark was not Ajax at all – yes, Ajax was arrogant, carefree, loud-mouth, over-relaxed team, but it was also an incredibly intelligent team, capable to read very quickly particular game and opponent and adapt approach permitting them to win. They were capable effortlessly to change tactics during ongoing match and, if that was needed, to become ruthless, ugly, defensive soldiers. No sentiments on the pitch – the hippies transformed into professionals, they were always proffesionals on the pitch. If legs needed to be broken in order of winning, then break legs. If closing the game was needed to neutralize some dangerous foe, then forget the artistry and close the game in some dull kicking the ball around the central line. Ajax had the players for such changes, though. Denmark did not – it was team knowing only how to play in attack, always trying to outplay the opponent and score. And if the opposition scored... well, we have to outscore them, simple and clear. It did not work against teams like Spain, teams asking for different approach, change of tactics. Ajax would never permit tricky Spaniard to get advantage of deadly Butragueno – most likely they would had kicked him to death. Most likely after scoring one goal, Ajax would had try to confuse the Spaniards with alternation of the tempo, would try to bait the known Spanish brutes into receiving yellow and red cards, so the get numerical advantage. Ajax would not try just to outplay Spain. Denmark was not able of anything else, but attack and attack – opening itself more and more for lethal counterattacks, exposing the vulnerability of its defense. Wonderful as it was, team Denmark was simplistic team and thus beatable not just by clever opponents, but almost by anybody, if their strikers were unlucky to score goals. Unlucky to make it 2-0, Denmark lost 1-5. And that looking the stronger team to the end of the match. As for old, slow, and heavy defense... there was not much to do about it. The only option was improvisation – Holland improvised in 1974 and 1978, but Piontek was either scared of taking a risk, or feared that improvisation would destroy his midfield, his greatest line on which everything depended. Well, Piontek did not have so many options at hand – Michels could risk in 1974, moving Haan back, for he still had other midfielders, but if Piontek moved back Lerby... the midfield was crippled right away. It was not that the coach did not try to change things in defense – Sivebaeck (yes, heavy and slow) was out – but that was the maximum. Unpleasant as it was, Denmark deserved to be eliminated, if one digs deeper with more objective mind. Still, too bad for football.