First Division. Well, Hungary was leading Eastern Europe in implementing professional elements to its football: it was the first Communist country to introduce sponsor names on team shirts. First, if not counting Yugoslavia. Not every club had a sponsor, but this was understandable – even liberal Communist regimes were slow and careful when introducing Western ways. There were also some practical difficulties: current leading clubs tended to belong to quite big local firms, so advertisement of foreign products seemed unlikely. One can see why the champions can get sponsors and popular, but presently weak, clubs would not, but still there was curious discrepancy – lowly Tatabanya was one of the first teams advertising foreign firms. Novelties apart, the season was not much: one team dominated everything; traditional powerhouses were desperately trying to avoid relegation and no new promising team emerged. The final table is a bit misleading, when looked at many years after: the relegated teams were exactly those expected to be relegated.

Well, no mystery about the last in the table – SZEOL AK were the hopeless outsider this season, ending with just 14 points. 15th was Eger SE, a team expected to be relegated as well, but they had 25 points and weak as they were, they were only one of 6-7 similarly weak teams. Anyhow, SZEOL and Eger went down.

MTK-VM (Budapest) survived: 14th with 27 points. True, they lost the leading role in Hungarian football long time ago, but who would thing they will stay so low? At least their decline was familiar.

MTK-VM (Budapest) survived: 14th with 27 points. True, they lost the leading role in Hungarian football long time ago, but who would thing they will stay so low? At least their decline was familiar.

Ferencvaros (Budapest) – 13th with 28 points. Now, this was a big plunge. Ferencvaros trying to escape relegation? Unbelievable. But fact. Managed to escape, though.

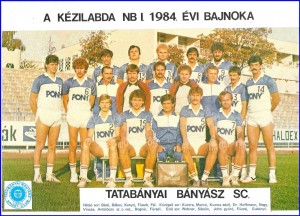

Tatabanya was 12th with 28 points too. This area of the table was painfully familiar to them, nothing new.

Pecsi MSC – 11th with 28 points. Like Tatabanya, they were in their familiar waters.

Ujpesti Dosza (Budapest) – 10th with 28 points. It was goal-difference placing them at the top of the weaklings, but it was a big drop down. They experienced the same crisis as their big rivals Ferencvaros.

Haladas VSE – 9th with 29 points. Nothing new about them, except may be they should having said ‘thank you’ to Ferencvaros and Ujpesti Dosza joining the bottom feeders.

Debreceni MVSC – 8th with 30 points. Mid-table position – traditionally, that was the most they aimed at, so nothing new.

Csepel SC (Budapest) – 7th with 30 points. The smallest and normally weakest of the big Budapest clubs, they rarely were among the title contenders. In view of grand failures of Ferencvaros, Ujpesti Dosza, and MTK, Csepel would be rather satisfied this year.

Bekescsaba – 6th with 30 points. Quite an unusual place for them – typically, they finished in the lower half of the table – but stable season. No better than most below them, except they performed well against direct rivals and benefited by that: if goal-difference counted, they would be 8th.

Vasas (Budapest) – 5th with 31 points. Nothing special. Looked like they recruited some stronger provincial players – no big stars, but given the general level of the league, enough help. Let’s make no mistake here: Vasas was closer to those relegated than to the leading club: they had only 6 points more than the 15th placed.

ZTE (Zalaegerszeg) – 4th with 34 points. Great season for them, but ZTE was unlikely club to stay at the top of the league for long. Scoring was a big problem for them.

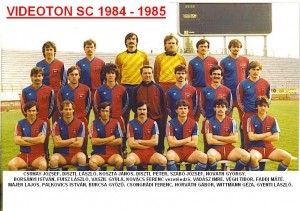

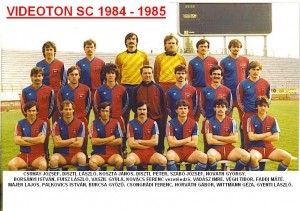

Videoton was the European sensation this season, but domestically little was added to their usual performance. A team to be treated with respect for years – they started their climb shortly after 1970 and after 1975 practically became established leading club, but not a title contender. Videoton managed to maintain a good squad for years – but it was a short squad and playing three tournaments was taxing them beyond the limit. No wonder Videoton was able only to fight for second place, but no blame for finishing 3rd: they lost the silver only on goal-difference.

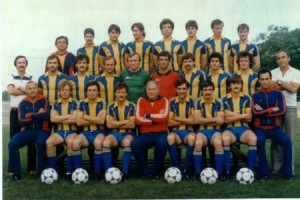

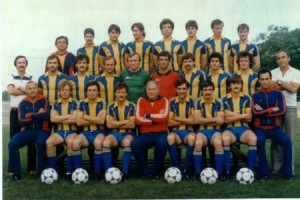

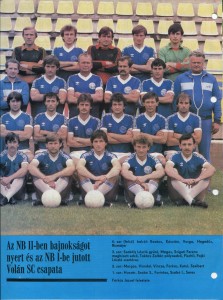

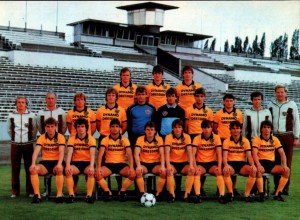

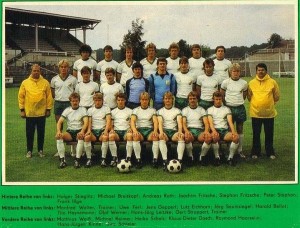

Raba ETO (Gyor) clinched 2nd place – like Videoton, they had 36 points, but better goal-difference. Like Videoton, they broke down the domination of Budapest and like Videoton they were unable to improve on their squad, but only managed to keep it good enough. Top row from left: Rubolt Péter, Menyhárt Ernő, Hlagyvik Gábor, Stark, Somogyi József, Rezi Lajos, Melis Béla, Csikós Lajos.

Middle row: Mészáros Ferenc, Preszeller Tamás, Orosz László gyúró, Kiss László pályaedző, Verebes József vezetőedző, Győrfi László pályaedző, Kiss Zsolt, Ulbert Tibor

Sitting: Csonka Gyula, Szíjártó László, Hannich Péter, Turbék István, Szabó Ottó, Szentes Lázár, Hajszán Gyula, Inczédi, Rugovics Vendel.

It was good season nevertheless – for provincial clubs, 2nd place is never a disappointment or failure.

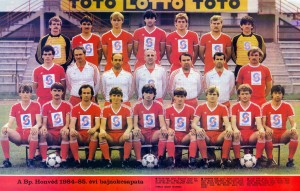

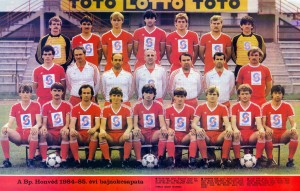

Honved (Budapest) easily won the championship. They were truly above everybody else, practically without rivals. Most of the best players were concentrated here and the greatest current star of Hungarian football, Lajos Detari, was leading the team. No wonder Honved reigned supreme, even if this team could not compete with the fantastic squad of the 1950s. It was enough, though, that no Hungarian team at the moment could compete with them. The only enemy was export… how long Honved may keep its stars and who could replace them was an open question.

![StahlBrandenburg_1984-85_1[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/StahlBrandenburg_1984-85_11-300x216.jpg)