The Soviet championship left mixed feelings at the end – it looked like a major change occurred, which may have been positive, but there was also uncertainty, because of sense of decline of powerful clubs. The first problem was related directly to the concerns about football in the lower levels: the championship had two hopeless outsiders, which occupied the last positions from start and never appeared able to move up. Both outsiders were recent second division members.

Newcomer Nistru (Kishinev) finished last with 10 points. Torpedo (Kutaisi) was 17th with 18 points. Their whole role this season was to give easy points away. The problems of both teams were obvious from start and the coach of Torpedo, Anatoly Norakidze, spelled out the hopeless situation as early as the 4th round of the championship: “We are starting to build a team from scratch again.” Every year starting anew, that was Torpedo’s fate for a long time. And no wonder – even if the purpose of second division, where Torpedo – and Nistru too – usually played was not merely to be a supplier of players, clubs like Torpedo had the same role on republican level. The leading club of Georgia was Dinamo (Tbilisi), so everybody else was to give their best players to the republican flagship. In return – old and no more useful players of Dinamo were eventually received. They did not last long, mostly because of age. And not everybody was willing to join the smaller club – there were other options, often much better. So, this year Torpedo again depended on former Dinamo players, some of them famous – Gabelia, Khizanishvili, and Kostava – but it was far from enough for a competitive team. Nistru was similar – representing republic not particularly great at football, Moldova, they had no local pool of players to chose from and depended on recruits from elsewhere, mostly Ukraine. The left-overs of Ukraine, for the leading republic had too many top level clubs and they were the first choice of the better players. It was clear before the season that Nistru needs stronger recruits, the club failed to find such, and at the end of the season was accused of neglecting selection. Thus, the whole role of the outsiders was to provide easy life to teams in deep trouble – but why worry, when relegation was out of the question? Well, there was a lot to worry about.

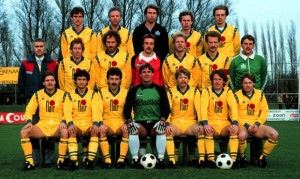

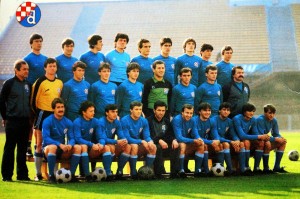

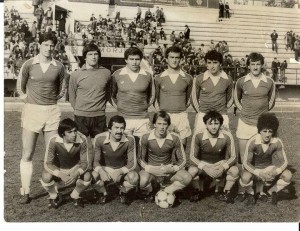

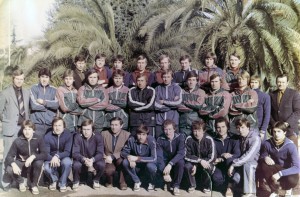

Dinamo (Tbilisi) finished 16th with 27 points. Only two years after dazzling Europe and winning the Cup Winners Cup, they were at the bottom of the table. The squad tells if all. Standing from left: D. Paikidze, G. Tchkareuli, T. Zhiba, T. Sulakvelidze, M. Meskhi, K. Mtchedlidze, A. Chivadze, K. Kereselidze, D. Mudzhiri, A. Andguladze, G. Ukleba.

First row: R. Shengelia, G. Dochia, N. Kakilashvili, G. Guruli, Z. Svanadze, G. Dzhokhadze, M. Arziani, V. Kopaleyshvili, D. Kudinov.

After its European triumph, Dinamo failed to reinforce essentially aging team – two years later there were few great players left: Chivadze, Sulakvelidze, Shengelia, and Gutzaev. Not a single strong midfielder and Gutzaev very close to the end of his playing days. For many, it was just temporary failure, one careless season, but in fact this year was the end of the great Georgian team – one of the traditionally strongest clubs in USSR was never to be strong again. It was the end.

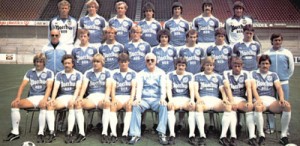

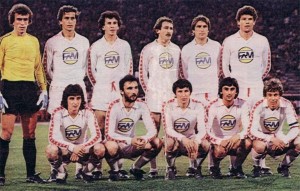

If Dinamo (Tbilisi) crisis came out of the blue, there was nothing new about the failure of their Moscow namesake: Dinamo struggled already for years, dropping out of the leading teams. And there was no end to trouble – may be because of policy. Year after year Dinamo recruited good players from elsewhere – good players, but not first rate and failing to improve the team. It was solid on paper, perhaps too solid. Minayev, Makhovikov, Gontar, Nikulin, and Novikov had their national team days gone for years already. Gazzaev was the only current national team member – but played scarcely and soon was out of consideration altogether. Bubnov, the only player of the pictured squad to become national team regular, moved to Spartak (Moscow), finished the season with his new club and practically became famous as Spartak player, not Dinamo’s. Although the squad suggested otherwise, Dinamo finished at the bottom of the league: 15th with 28 points.

If Dinamo (Tbilisi) crisis came out of the blue, there was nothing new about the failure of their Moscow namesake: Dinamo struggled already for years, dropping out of the leading teams. And there was no end to trouble – may be because of policy. Year after year Dinamo recruited good players from elsewhere – good players, but not first rate and failing to improve the team. It was solid on paper, perhaps too solid. Minayev, Makhovikov, Gontar, Nikulin, and Novikov had their national team days gone for years already. Gazzaev was the only current national team member – but played scarcely and soon was out of consideration altogether. Bubnov, the only player of the pictured squad to become national team regular, moved to Spartak (Moscow), finished the season with his new club and practically became famous as Spartak player, not Dinamo’s. Although the squad suggested otherwise, Dinamo finished at the bottom of the league: 15th with 28 points.

Ararat (Ereven) – 14th with 29 points. A sorry example, which Dinamo (Tbilisi) failed to see – Ararat did not reinforce its great winning team of the first half of the 1970s and when it aged, Ararat simply went into decline. And that was that.

Ararat (Ereven) – 14th with 29 points. A sorry example, which Dinamo (Tbilisi) failed to see – Ararat did not reinforce its great winning team of the first half of the 1970s and when it aged, Ararat simply went into decline. And that was that.

Neftchi (Baku) – 13th with 30 points. The usual lowly place, if they had good year and were not relegated.

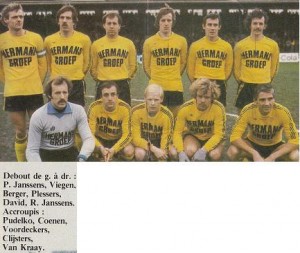

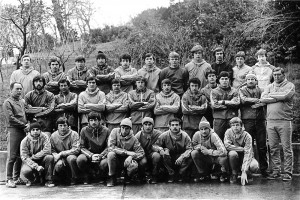

CSKA (Moscow) – 12th with 32 points. Just struggling to stay in the league… their decline started before Dinamo’s, as part of the great decline of Moscow football. Once upon a time it was mighty battle between CSKA and Dinamo for the title, they were the leading clubs – now it was a derby in the bottom of league. Front row from left: D. Galyamin, N.Bulgakov, E.Drozhzhin, A.Tarhanov, V.Plotnikov , ?, V.Kruglov.

CSKA (Moscow) – 12th with 32 points. Just struggling to stay in the league… their decline started before Dinamo’s, as part of the great decline of Moscow football. Once upon a time it was mighty battle between CSKA and Dinamo for the title, they were the leading clubs – now it was a derby in the bottom of league. Front row from left: D. Galyamin, N.Bulgakov, E.Drozhzhin, A.Tarhanov, V.Plotnikov , ?, V.Kruglov.

Middle row: V.Grechnev, V.Chetverikov (assistant coach), E.Veschev (doctor), V.Novikov, Yu.Shishkin, B.Kuznetsov, Yu.Chesnokov, P.Nesterov, V.Kardivar (administrator)

Third row: S.Pasechnik, V.I.Kornadut (political officer), Yu.Adzhem, V.Kovach, V.Glushakov, V.Kobyscha, G.Shtromberger, M.Plahetko (team cheif)

Forth row: S.Shaposhnikov (assistant coach), A.Shesternev (coach), I.Kurakin, V.Kolyadko, A.Samohin.

Same case as their rivals, Dinamo – good on paper, but not so on the pitch.

Metalist (Kharkov) – 11th with 32 points. Nothing special, but not alarming performance. Rather, the opposite – the team was establishing in the top league, so it was not bad. Just adjusting.

Pakhtakor (Tashkent) – 10th with 35 points. Not bad for them, even looked like the team finally recovered from the devastating airplane crash, which killed the whole team few years back. It was illusionary recovery, though.

Looked like Shakhter (Donetzk) lost its edge and dropped to its old mid-table position – 9th with 35 points. Front row from left: S. Morozov, V. Grachev, A. Varnavsky, M. Sokolovsky, S. Akimenko, I. Petrov, S. Yashtenko, V. Pyanykh.

Looked like Shakhter (Donetzk) lost its edge and dropped to its old mid-table position – 9th with 35 points. Front row from left: S. Morozov, V. Grachev, A. Varnavsky, M. Sokolovsky, S. Akimenko, I. Petrov, S. Yashtenko, V. Pyanykh.

Standing: O. Globukov – doctor, I. Yurchenko, Yu. Fishelev – administrator, V. Elinskas, V. Rudakov, A. Sopko, I. Simonov, V. Parkhomenko, M. Kalinin – team chief, V. Nossov – coach, ?, ?.

However, still solid and still the second ranking Ukrainian club. And still capable of winning.

Chernomoretz (Odessa) – 8th with 37 points. Good season,giving lots of hope locally. Standing from left: A. Doroshenko, V. Fink, V. Sakhno, V. Kuzmin, V. Rodionov, V. Sidnev, S. Pavlenko, V. Zubkov, A. Skripnik, V. Prokopenko, V. Nechaev, V. Ploskina, A. Degtyarev, referees V. Lysenko, Shevchuk, Mardar.

First row: I. Hakonechny, V. Pasulko, S. Zharkov, I. Belanov, Yu. Romensky, A. Polishtuk, G. Sapozhnikov, I. Shary, I. Sokolovsky.

The picture is from a memorial game against the ‘greatest’ Chernomoretz squad, winning bronze medals in 1974. The veterans – in dark, current squad in white. Same predicament, though… to a point, depending heavily on Dinamo (Kiev) – good players going there (Igor Belanov), hopefully decent players coming from there (Yury Romensky).

The picture is from a memorial game against the ‘greatest’ Chernomoretz squad, winning bronze medals in 1974. The veterans – in dark, current squad in white. Same predicament, though… to a point, depending heavily on Dinamo (Kiev) – good players going there (Igor Belanov), hopefully decent players coming from there (Yury Romensky).

Dinamo (Kiev) – in dire straits and 7th with 38 points. A very disappointing season, which was partly due to injuries of key players, particularly the one of Buryak. Standing from left: Demyanenko, Buryak, Blokhin, Chanov, Makhinya, Bal.

Dinamo (Kiev) – in dire straits and 7th with 38 points. A very disappointing season, which was partly due to injuries of key players, particularly the one of Buryak. Standing from left: Demyanenko, Buryak, Blokhin, Chanov, Makhinya, Bal.

Front row: Lozinsky, Zavarov, Dumansky, Guyganov, Evseev.

Injuries or not, it was strange, for Dinamo had the deepest squad in the league and provided most players to the national team. Even Lozinsky was still a member of the national team. Perhaps the reason for the failure was that Lobanovsky was not coaching Dinamo – he was coaching the national team and Yury Morozov was head coach. Well, Morozov was leading coach, even heading the national team. But he was unable to keep Dinamo at top – of course, the usual excuses were made: the players were tired, for they had too many games on too many fronts – domestic, European club torunaments, national team duties. And, of course, it was lame excuse – this was the best Soviet squad by far. Even the reserves were better players than most first league squads. Practically the same squad will win the Cup Winners Cup in 1986. Perhaps the real reason was midfield instability – Veremeev was listed at the beginning of the season as a player, but he did not play at all, coming to retirement at 35. Buryak was already 30 years old and after his injury there was nobody to handle midfield and organize the play. It came to the point Dinamo worried whether Sorokalet would be fit or not to start a game… Dinamo reduced to dependency on the fitness of second-rater (at best) as Sorokalet.

Torpedo (Moscow) edged Dinamo (Kiev) and took 6th place with 38 points. Ailing from the general Moscow sickness – solid players, but players who already reached their peaks. Getting no better and having no way to get better. Mid-table was their limit, there they were. There was some comfort, though – Torpedo performed better than Dinamo and CSKA.

The big wonderful surprise – Zalgiris (Vilnius) finished 5th with 39 points. Once upon a time Zalgiris played a bit of first division football, but without any success, so they were seen as absolute beginners: not a single player ever appeared in the top league before this year. Not only that, but this squad played 3rd division football just a few years back. The nobodies was expected to be relegated right away, but instead they played wonderfully and finished high in the table. Talented bunch, but observers were careful with praise – looked like one-time wonder. These were third division players after all – may be enthusiasm carried them this year, aided by other teams not paying attention to them, but the next year everything will become clear. And will be, but the way the skeptics thought: Zalgiris will be one of the strongest Soviet teams to the end of USSR and ‘third league’ players will become leading players, eventually ending playing professionally abroad. Zalgiris became also the a positive example, countering dark criticism of lower divisions: they managed to make a strong team from local boys, moved from complete obscurity to leading position, the system worked, therefore. True, but omitting one thing: since Lituania never had strong football, nobody was looking for good players there. Talent survived by default – and when suddenly talent emerged, it was too late to grab it: the Perestroika started, awakening local nationalism and providing some ways for financing clubs and paying players, so there was little chance Lituanians to be tempted by other clubs. Zalgiris proved everybody wrong, but not this year.

The big wonderful surprise – Zalgiris (Vilnius) finished 5th with 39 points. Once upon a time Zalgiris played a bit of first division football, but without any success, so they were seen as absolute beginners: not a single player ever appeared in the top league before this year. Not only that, but this squad played 3rd division football just a few years back. The nobodies was expected to be relegated right away, but instead they played wonderfully and finished high in the table. Talented bunch, but observers were careful with praise – looked like one-time wonder. These were third division players after all – may be enthusiasm carried them this year, aided by other teams not paying attention to them, but the next year everything will become clear. And will be, but the way the skeptics thought: Zalgiris will be one of the strongest Soviet teams to the end of USSR and ‘third league’ players will become leading players, eventually ending playing professionally abroad. Zalgiris became also the a positive example, countering dark criticism of lower divisions: they managed to make a strong team from local boys, moved from complete obscurity to leading position, the system worked, therefore. True, but omitting one thing: since Lituania never had strong football, nobody was looking for good players there. Talent survived by default – and when suddenly talent emerged, it was too late to grab it: the Perestroika started, awakening local nationalism and providing some ways for financing clubs and paying players, so there was little chance Lituanians to be tempted by other clubs. Zalgiris proved everybody wrong, but not this year.

Zenit (Leningrad) – 4th with 40 points. Like Zalgiris, understimated. Good year, but Zenit had such good years – occasionally – before, especially when some other teams underperformed. Their attacking line was acknowledged as perhaps the strongest in the country at the moment – Kazachenok, Gerasimov, Klementyev, Zheludkov – helped by young rapidly emerging midfielder – Larionov. At the moment, that was all – rather small group of impressive players for continual success. Zenit was still seen largely as routine mid-table team. Just having good year. But it was not entirely that and observers were careful, preferring silence: there was something stirring, smaller clubs moved up and bumped the big names. Metalist (Kharkov) playing well, Zalgiris 5th, Zenit 4th – and Dinamo (Kiev) behind, Dinamo (Tbilisi) – at the bottom, Moscow Dinamo and CSKA – practically outsiders. And two other small clubs – ahead of everybody.

Zenit (Leningrad) – 4th with 40 points. Like Zalgiris, understimated. Good year, but Zenit had such good years – occasionally – before, especially when some other teams underperformed. Their attacking line was acknowledged as perhaps the strongest in the country at the moment – Kazachenok, Gerasimov, Klementyev, Zheludkov – helped by young rapidly emerging midfielder – Larionov. At the moment, that was all – rather small group of impressive players for continual success. Zenit was still seen largely as routine mid-table team. Just having good year. But it was not entirely that and observers were careful, preferring silence: there was something stirring, smaller clubs moved up and bumped the big names. Metalist (Kharkov) playing well, Zalgiris 5th, Zenit 4th – and Dinamo (Kiev) behind, Dinamo (Tbilisi) – at the bottom, Moscow Dinamo and CSKA – practically outsiders. And two other small clubs – ahead of everybody.

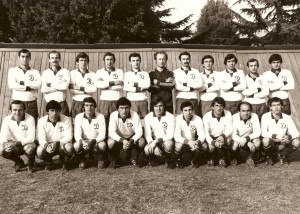

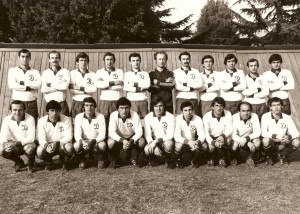

The surprise champions of 1982 finished 3rd this year with 43 points. Third row from left: Leonid Vassilevsky – administrator, Sergey Borovsky, Viktor Shishkin, Georgy Kondratiev, Vassily Dmitrakov – doctor, Igor Belov, Yury Pudyshev, Viktor Sokol, Anatoly Ussenko – masseur.

The surprise champions of 1982 finished 3rd this year with 43 points. Third row from left: Leonid Vassilevsky – administrator, Sergey Borovsky, Viktor Shishkin, Georgy Kondratiev, Vassily Dmitrakov – doctor, Igor Belov, Yury Pudyshev, Viktor Sokol, Anatoly Ussenko – masseur.

Middle row: Valery Me;nikov, Oleg Alekseenko, Yury Trukhan, Arkady Batalov, Yury Kurbyko, Sergey Aleynikov, Viktor Yunushevsky, Liudas Rumbutis, Andrey Zygmantovich.

Sitting: Igor Gurinovich, Sergey Gotzmanov, Mikhail Vergeenko – assistant coach, Leonid Garay – team chief, Veniamin Arzamastzev – coach, Ivan Savostikov – assistant coach, Yury Kurnenin, Petr Vassilevsky.

Frankly, Dinamo was not expected to repeat its success, let alone to build a dynasty. It was expected to play fairly well, though – on inertia. And inertia it was, for Dinamo was in the same predicament as few earlier champions – Ararat and Zarya. Small club to begin with and having not all that strong squad, it needed fresh recruits to solidify its original victory and keep going strong. But the club either missed the moment of opportunity or was not in position to use it at all, so instead of reinforcement there were already first losses: the significant one was the coach Eduard Malafeev, who went to work with national teams. Less significant was the retirement of the long serving goalkeeper Vergeenko, who became assistant coach of the team. So, it was the same team, with some key players getting older and inevitable worse and new new bright talent to even replace them. Still, Dinamo was lucky to keep its best players – Borovsky, Aleynikov, Gotzmanov, Zygmantovich, and Gurinovich. Of them only Borovsky was regular national team player at the moment, which was another sign that Dinamo was not taken all that seriously. Riding inertia, they finished well, but were not a title contender this year at all.

Whatever were the problems of Soviet football, but this championship ended on very excited note: the champion was decided in the last round in direct clash between the pretenders. Dnepr (Dnepropetrovsk) was leading by 2 points and hosted the decisive game. Spartak (Moscow) had better goal-difference and was in excellent combative form. It was very rare occurrence – happened only once before, in 1959. A big dramatic final of the long championship. Spartak needed a win and if they got it, they were not to be champions, but a play-off had to be played, according to the rules. Dnepr had the home turf advantage and needed just a tie – in fact, back in 1959 the decisive game was tied. This time was different, just a bit – Dnepr went forward, got 2-0 lead and kept it to the end – it was 4-2 at the end and USSR got their brand new champion, thus rounding the number of champions to 10.

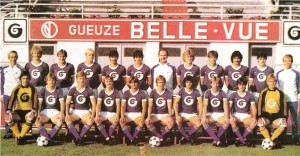

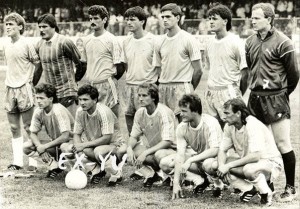

Spartak (Moscow) got silver, which did not pleased them at all. Standing from left: Yu. Vasilkov, N. Starostin, A. Bubnov, Yu. Gavrilov, K. Beskov – coach, R. Dassaev, S. Bazulev, V. Gladilin.

Spartak (Moscow) got silver, which did not pleased them at all. Standing from left: Yu. Vasilkov, N. Starostin, A. Bubnov, Yu. Gavrilov, K. Beskov – coach, R. Dassaev, S. Bazulev, V. Gladilin.

Crouching: F. Cherenkov, Yu. Reznik, E. Mileshkin, V. Sochnov, E. Kuznetzov, B. Pozdnyakov.

Once again Spartak failed to win the title and that was too much for many considering Spartak the best Soviet club at the time. But was it? The squad above tells for itself – a strange mixture of world class players and little known guys. Some promising youngsters, some experienced second-raters, a veteran, two players seemingly just making the numbers. And that because of injuries – Oleg Romantzev, Sergey Shvetzov, Sergey Rodionov, and Edgar Gess were out most of the time. The team was shaky and at half-season there were no hopes for medals at all – Spartak was 9th. In the second half, though, Spartak suddenly came back to life and won 14 straight games, thus, having a chance to win at the end, but still lost. Konstantin Beskov, for many, was the best coach in the country and Starostin had the reputation of the best club manager, yet Spartak displayed a fundamental flaw during their long reign: it was never deep enough team, especially if compared to Dinamo (Kiev). Behind the regulars there were rather suspect reserves, but the transfer policy never changed – it looked like Spartak only replaced leaving good players with the same number of classy newcomers, adding a few young promising youngsters, but hardly noticed before and, as a rule of thumb, one or two veterans from other clubs. The newcomers rarely lasted more than a season, mostly because they disappointed, veterans did not last long either, because of inevitable retirement, so the next year Spartak was in exactly the same situation as the previous one. They lost Sergey Shavlo before this season, who was called to serve in the Army and thus played for second division Iskra (Smolensk). Another decent player moved to SKA (Rostov). The new recruits were typical – two of them were released quickly. Others – Mileshkin and Pozdnyakov on the photo above – made the team, but one could say that happened largely because regulars were injured. Valery Gladilin came back from Kairat (Alma-ata) to finish his career with his original club – the peak of Gladilin was almost 10 years ago. Yury Reznik was well known name, but hardly a star and also he reached his limit already. Only late transfer was really worthy – the central defender Aleksandar Bubnov, who arrived from Dinamo (Moscow). Meantime became clear that Spartak would not keep Reznik for long. Meantime 4 regulars were lost to injuries – Shvetzov practically missed the whole season, Romantzev and Rodionov – half of the season, Gess – almost half of the season. And there was nobody to replace them. Bubnov joined Spartak after the first half of the season was finished. Spartak was extremely vulnerable for it practically depended on 11 regulars and any injury badly rattled the short squad. One result of this permanent problem had particularly unhappy consequences – arguably, the best midfielder in the country at that time – Fedor Cherenkov – was overused, which cut short his career. The other result was empty hands – since Spartak came back from second division, they were the most stable performers in the country – 5th in 1978, champions in 1979, 2nd in 1980, 2nd in 1981, 3rd in 1982, and now – 2nd one more time. Stable, but without a title… stable, but quite distant from the leaders, not true title contenders – this season was the first time after 1979 Spartak had a real chance to win the championship and they blew it.

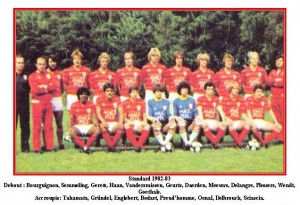

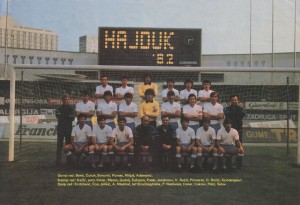

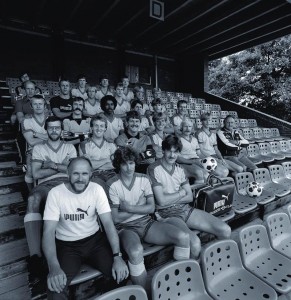

Dnepr (Dnepropetrovsk) did not miss its chance and won its first title. Standing from left: A. Tevs – assistant coach, E. Zhuchkov – assistant coach, A. Dilay, P. Kutuzov, Yu. Mirgorodsky, V. Bagmut, V. Konsevich, L. Koltun – assistant coach, S. Krakovsky, G. Zhizdik – team chief, V. Lyuty, O. Protassov, R. Konafotzky – administartor, G. Litovchenko, A. Azarenko – assistant coach, V. Emetz – coach.

Dnepr (Dnepropetrovsk) did not miss its chance and won its first title. Standing from left: A. Tevs – assistant coach, E. Zhuchkov – assistant coach, A. Dilay, P. Kutuzov, Yu. Mirgorodsky, V. Bagmut, V. Konsevich, L. Koltun – assistant coach, S. Krakovsky, G. Zhizdik – team chief, V. Lyuty, O. Protassov, R. Konafotzky – administartor, G. Litovchenko, A. Azarenko – assistant coach, V. Emetz – coach.

First row: A. Pogorelov, O. Taran, N. Chernysh – doctor, O. Serebryansky, V. Ustimchik, A. Lysenko, N. Fedorenko, N. Pavlov, V. Kuznetzov, S. Puchkov.

Surprise winners, but in the same time not a big surprise – rather, representing the change taking place: smaller, previously insignificant clubs, moving up and pushing traditional powers back. Dinamo (Minsk) won the 1982 championship, now – Dnepr. There were also Metalist (Kharkov), Zenit (Leningrad), and newcomer Zalgiris (Vilnius) – an increasing group of underdogs challenged traditional leaders and they had one thing on common: having no real stars, they depended on collectives of enthusiastic second-raters, who compensated the obvious lack of skills with physical play, constant pressure, staying alert – tightly knit outfits, who were able to hold their own against big names and took advantage from any slip, occasional or not, of the big names. And having no real stars helped them to keep and even improve their squads – nobody was interested in such players, some of them already tried and discarded by the biggies. Dnepr was the best sample of the new breed of strong teams so far – better than Dinamo (Minsk): they had no star at all, and that included their home-grown coach Vladimir Emetz, pracitcally ‘discovered’ this very year thanks to the title. His boys were considered local – home-grown too – which was only partially true. The squad was made of similar players, who, lacking great skills, compensated with disciplined collective approach, based on physical pressure and not shying away from vicious tackles. Since they were players of the same mold, there was no big trouble if someone was injured or suspended – the back-up was pretty much of the same kind: physically fit runner. As a team, Dnepr more or less roll over the opponent – sometime this was not enough, but more often it was. It was all or nothing too – Dnepr did not look for ties, but for wins. And they most of all this year – 22 matches. They also lost 7 games and tied 5, they scored most goals in the championship – 63, their defense was leaky, allowing 36 goals in 34 games (7 teams had better defensive records, led by Spartak, which allowed only 25 goals in its net). All or nothing worked – Dnepr finished 4 points ahead of Spartak. Yet, it was clearly a victory of the collective approach – observers had difficulties speaking of the new champions as individuals. Some players were familiar… but either as second raters or failures. Seasoned veterans like Ustimchik, Pogorelov, and Zuev not only had their best years long time ago, but also with other clubs – and their best was not particularly great: Zuev at his prime was just eternal reserve of Dinamo (Kiev). At least he played over there – others were discarded quickly from the big club: Serebryansky, for instance. The best example was Oleg Taran, noticed when he was 16-years old and included in the junior national team. But his future was dark – Dinamo (Kiev) was not happy with his skills and had no intention to keep him. And he went to Chernomoretz (Odessa), impressed nobody, moved to CSKA (Moscow), failed again, and finally arrived in Dnepr as a new recruit for 1983 season – now he was 23-years old and pretty much written off with only 42 league games and 3 goals so far. But he fitted in, played well and finished the season as the best scorer of the champions with 13 goals – which was not much. Just enough for journalists to find something ‘extraordinary’ to praise – and not enough at all for any club to show interest in him. And the rest of the team was similar – even talented guys like Lyuty were seen talented enough to get, particularly by Dinamo (Kiev), which routinely took players from ‘subservient’ Ukrainian clubs. Dinamo was in trouble, Dnepr was champion,and still Dinamo did not see anyone worth to get from the fresh champions. But unlike other clubs, Dnepr was thinking of the future and did not stuck in keeping the existing squad until they retired – two bright youngsters were already in the team and given playing time: Genady Litovchenko (20 years old) and Oleg Protassov (19-years old). They were not famous yet, but will be in the next year or two (and, yes, Dinamo Kiev will snatch Protassov eventually). Dnepr continued the policy of searching and introducing new players, which was the right approach and unlike Dinamo (Minsk) and Zenit (Leningrad) Dnepr established itself as leading Soviet club in the 1980s. Never exciting team, but given the predicament of a small club, the best approach to stay competitive.

One more look at the new Soviet champions – and good to keep them inn mind, for this was not the only year focused on Dnepr – they were not one-time wonder.

One more look at the new Soviet champions – and good to keep them inn mind, for this was not the only year focused on Dnepr – they were not one-time wonder.

![Telstar8283[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Telstar82831-300x211.jpg) Telstar finished 15th with 20 points. Once upon a time they played in the top league, now they were at the bottom of the second division. Well, there was no relegation further down in Holland, so Telstar could play second tier football as long as they had enough money to pay the bills.

Telstar finished 15th with 20 points. Once upon a time they played in the top league, now they were at the bottom of the second division. Well, there was no relegation further down in Holland, so Telstar could play second tier football as long as they had enough money to pay the bills. Spcl. Cambuur was unlucky – they lost promotion by a single point. They also represented a new trend – British players were coming to play in Holland. Not the famous ones, but those hardly known – two such players helped Cambuur this season: Kelly Herrington and Mark Paine.

Spcl. Cambuur was unlucky – they lost promotion by a single point. They also represented a new trend – British players were coming to play in Holland. Not the famous ones, but those hardly known – two such players helped Cambuur this season: Kelly Herrington and Mark Paine. FC Den Bosch won the promotional tournament with 9 points. Well done and fair too, for Den Bosch were 3rd in the final table of the championship.

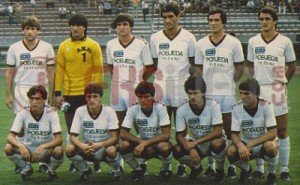

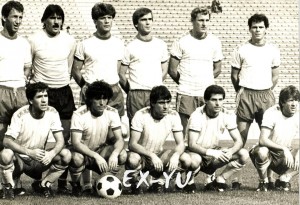

FC Den Bosch won the promotional tournament with 9 points. Well done and fair too, for Den Bosch were 3rd in the final table of the championship. FC Volendam was 2nd the championship with 40 points and thus directly promoted. Third row from left: Cees de Koning, Theo Mooijer, Jack Kemper, Klaas Tuyt, Frank Kramer, Wim Kwakman

FC Volendam was 2nd the championship with 40 points and thus directly promoted. Third row from left: Cees de Koning, Theo Mooijer, Jack Kemper, Klaas Tuyt, Frank Kramer, Wim Kwakman