The aftermath. Commentaries and evaluations of the World Cup continued for months, as ever, and summery of them would be something like that:

Nothing particularly new was shown at the finals. Nothing revolutionary for sure – there was evolution only, into something named ‘rational football’. By now, elements of total football were a must – changing positions, covering the whole field, pressure of the opponent, physical fitness. As a whole, the defensive elements of the old total football were present, but a lot of the real strength of the it – the attacking ones, were not much in evidence. Rational football was pretty much that and it had something cold and cynical at its roots: overrun the opponent and break it down, no matter how. ‘Professional fouls’ became the norm: it was even easier to kick down the opponent and stop their attack in early stage than trying to get the ball cleanly. Only victory mattered and victory became quite a wide term after the shameless meeting of West Germany and Austria – one can get what they want even by losing. But nothing else than final victory mattered anymore, it was a war and instead of total football, there was total war.

The torn jersey of Ardiles against Italy exemplified best the new philosophy at its ugliest.

The new formula was generally seen as successful: 24 teams was not the perfect number, but it was a matter of refining only. On the positive side were the outsiders – with the exception of El Salvador, the rest played well. The biggest revelation was the wonderful performance of the African teams – they were up to date tactically and pretty much equal to the Europeans and South Americans. Asian teams obviously improved too – to give more spots to the ‘developing world’ was clearly a step in the right direction. Out of 6 ‘outsiders’ only one – El Salvador – equaled the old notion of an outsider.

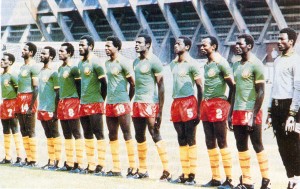

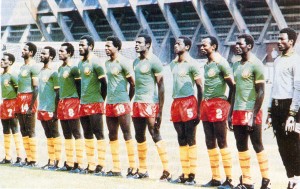

Cameroon was arguably the strongest ‘outsider’ and the big discovery, coming very close to reaching the second stage, along with Algeria, which was plainly robbed of advancing, but Cameroon left stronger and more lasting impression – they were truly equal to the ‘big teams’. New Zealand, Kuwait, and Honduras lost and were still weaker, yet, they played competent football and no fear.

Cameroon was arguably the strongest ‘outsider’ and the big discovery, coming very close to reaching the second stage, along with Algeria, which was plainly robbed of advancing, but Cameroon left stronger and more lasting impression – they were truly equal to the ‘big teams’. New Zealand, Kuwait, and Honduras lost and were still weaker, yet, they played competent football and no fear.

Referees are always criticized, but seemingly this time there were too many mistakes – to the point that it was questionable are the referees up to date with the modern game. It is difficult to say which incident was the worst – Schumacher sending Battiston to hospital for months, almost killing him; Gentile systematically destroying the best players of the opposite team; the penalties given to Spain or the penalties not given to USSR.

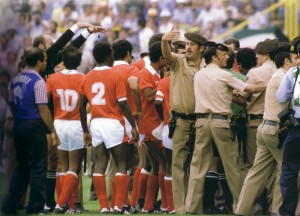

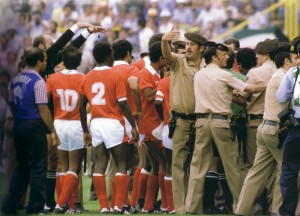

Perhaps the accident of the long stoppage during the France – Kuwait match, involving the Police was the worst – the Soviet referee Stupar did the unthinkable: bending under outside pressure, changing his mind, and disallowing a goal already called a score. It was not mere mistake and it was not putting a blind eye – it was reversing a decision, because somebody from the stands said so. The shame of the meeting between West Germany and Austria, however, showed entirely new problem, going outside the rules – the teams clearly did not play, fixing convenient for both result in the very beginning. Yet, technically, there was nothing to be done – they moved the ball around. Wasting time was done for years, but as long as the ball moves… it was inside the rules.

Perhaps the accident of the long stoppage during the France – Kuwait match, involving the Police was the worst – the Soviet referee Stupar did the unthinkable: bending under outside pressure, changing his mind, and disallowing a goal already called a score. It was not mere mistake and it was not putting a blind eye – it was reversing a decision, because somebody from the stands said so. The shame of the meeting between West Germany and Austria, however, showed entirely new problem, going outside the rules – the teams clearly did not play, fixing convenient for both result in the very beginning. Yet, technically, there was nothing to be done – they moved the ball around. Wasting time was done for years, but as long as the ball moves… it was inside the rules.

Fans. Hooliganism was still British phenomenon, but it was developing to the point when it was actually preferred Birtish teams not to reach finals. There was no other solution so far, especially because violence happened largely outside the stadiums. The biggest threat were the English fans.

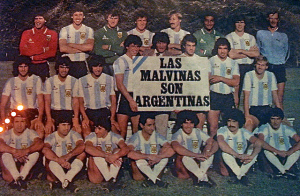

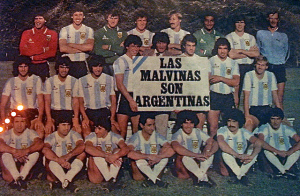

Politics. This was coming to the realm of the exotic – the Falkland Islands war had importance before the beginning of the World Cup: England considered to withdrawal, but decided to play.

The Argentines made a patriotic photo of themselves, which was almost grotesque – foorball players are supposed to smile at such photos, and they did. But a war is hardly a laughing, jolly matter. At the end, only Ardiles suffered from the conflict – he had to move to play in France for awhile, although neither he, nor Tottenham Horspur wanted that.

The Argentines made a patriotic photo of themselves, which was almost grotesque – foorball players are supposed to smile at such photos, and they did. But a war is hardly a laughing, jolly matter. At the end, only Ardiles suffered from the conflict – he had to move to play in France for awhile, although neither he, nor Tottenham Horspur wanted that.

Two records were set:

Norman Whiteside of Manchester United and Northern Ireland became the youngest player ever, playing at World Cup finals – he bettered Pele by few months, still 17-years old in round numbers. And it is a record unlikely to be bettered.

Norman Whiteside of Manchester United and Northern Ireland became the youngest player ever, playing at World Cup finals – he bettered Pele by few months, still 17-years old in round numbers. And it is a record unlikely to be bettered.

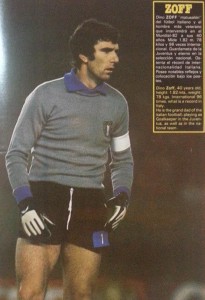

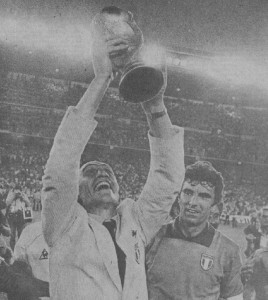

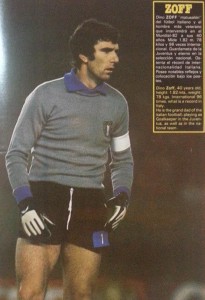

At 40, Dino Zoff became the oldest player to appear at World Cup finals – his record was bested in 2014, but he also became the oldest world champion, which very likely is not going to be equaled or bested.

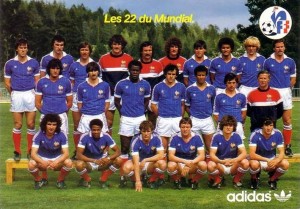

Two teams captured the minds, leaving many observers to optimistic statements – Brazil and France.

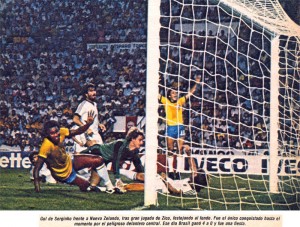

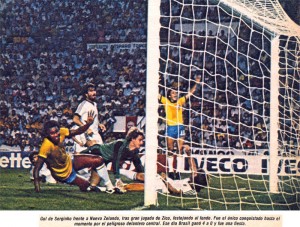

Football was alive, because of them and they introduced pleasant styles, bringing joy back to the game. But it was painfully clear that ‘rational’ football was getting the upper hand – both artistic teams were eliminated by teams with the opposite philosophy. Compared to the brutal teams, thinking of war, not of fun, Brazil and France appeared naïve. They also made very clear that the new reality required strong players at every position – may be not great players, but competent and strong above average: both France and Brazil lacked good goalkeepers and paid dearly for that – it was no longer possible to compensate a weak position by simply outscoring the opponent.

Football was alive, because of them and they introduced pleasant styles, bringing joy back to the game. But it was painfully clear that ‘rational’ football was getting the upper hand – both artistic teams were eliminated by teams with the opposite philosophy. Compared to the brutal teams, thinking of war, not of fun, Brazil and France appeared naïve. They also made very clear that the new reality required strong players at every position – may be not great players, but competent and strong above average: both France and Brazil lacked good goalkeepers and paid dearly for that – it was no longer possible to compensate a weak position by simply outscoring the opponent.

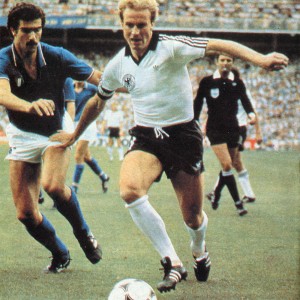

Injuries – an old and inevitable plague, but it looked like no other World Cup was so much affected by injuries. Rummenigge, Keegan, Boniek, Platini, and others were either not fit and suffering during the tournament, or missing key games. Perhaps Belgium paid the highest price – with van der Elst arriving injured and Pfaff and Gerets getting injured early in the tournament, Belgium was simply destroyed. Current football was collective and individuals seemingly mattered less, yet, it became clear that results depended mostly on key stars – without them collectivity was not lost, but the team was losing, not winning. But the new kind of players were pretty much similar work-horses and the absence of a star was getting nearly fatal – back in 1962, Brazil had enough talent to win the World Cup without injured Pele. It was no longer possible in 1982, almost no team had a player capable of replacing a star – and the coaches, without options and fearing a loss, preferred to field injured players, even when it was clear they contribute next to nothing.

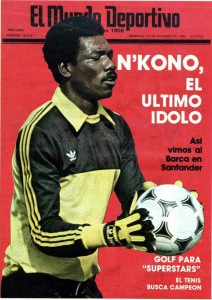

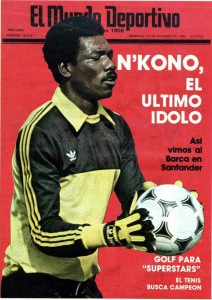

Discoveries. The World Cup was still the place to find hew talent and a market place. For most of the world, it was the moment to see at last those only heard of – Socrates, Falcao, Maradona. Along with them were the entirely unknown, like Thomas N’Kono. Frankly, not much real discoveries were made and Maradona underperformed. But considering the transfer contracts, the World Cup remained the number one place to get noticed or confirm one’s worth – Platini and Boniek signed with Juventus, Pfaff with Bayern (with specific clause about behavior, for Pfaff had a record of short temper bursts and misconduct), N’Kono with Espanol, Maradona with Barcelona. Africans moved to Europe, South Americans too, the New Zealander Winton Ruffer was not missed and also got European contract – the World Cup was important and players knew it well – this was giving hope for the future, for players were going to try their best at the finals to get noticed.

Thomas N’Kono, one of the genuine discoveries of the World Cup, instantly becoming a star.

The best of the finals were both obvious and controversial – yes, there were discoveries and players performing more than well. Lato, for example, who got a second wind. Others did not satisfy at all. Yet, no matter what people saw and what journalists commented during the tournament, the team of the World Cup displayed something else: Dino Zoff (Italy), Luizinho (Brazil), Junior (Brazil), Claudio Gentile (Italy), Fulvio Collovati (Italy), Zbigniew Boniek (Poland), Falcao (Brazil), Michel Platini (France), Zico (Brazil), Paolo Rossi (Italy), Karl-Heinz Rummenigge (West Germany). The new World champions got most players, as ever, but some were here on reputation, rather than actual performance, or because there were no really great players as some posts. The very system – 4-4-2 – suggested the change, favouring ‘realistic’ football – fewer strikers. Paolo Rossi was voted best player of the tournament, which was a bit suspect – like in 1978, there was no really fascinating and great player from start to end, and those playing well at the last stages were preferred. Rossi also was the best scorer – with 6 goals, all scored in the last three games. Not much… no more great scorers, was the sad conclusion.

Maradona and Socrates – both out of the best 11, but voted among the top 15 players of the championship. Socrates was great, Maradona – almost nothing. He particularly failed a s leader and many felt he was greatly inflated player. That was also a brief summary of the finals – highs and lows, fulfilled and unfulfilled expectations, and the sad reality of ‘realistic’ football – both players went home early. The third player of similar fame and caliber – Platini – fared differently:

Maradona and Socrates – both out of the best 11, but voted among the top 15 players of the championship. Socrates was great, Maradona – almost nothing. He particularly failed a s leader and many felt he was greatly inflated player. That was also a brief summary of the finals – highs and lows, fulfilled and unfulfilled expectations, and the sad reality of ‘realistic’ football – both players went home early. The third player of similar fame and caliber – Platini – fared differently:

He performed as expected, coming to his peak. He led France as a true leader and to a higher point than Brazil and Argentina. And he was a problem in the same time, noticed well before the finals – France was often stronger and certainly more collective without him. Without him, France was losing leadership, some creativity, and scoring power. With him it was not so together and was a weaker fighter. Peculiar problem for Michel Hidalgo, but also a general problem with the establishment of ‘realistic football’ – artistry was becoming liability and there was no real place for imaginative players. Better play like the Germans – no fun workaholics, extracting positive result at the end.

More or less, that was the summary of the 1982 World Cup.

This is picture of Al-Ahly in 1981, which at least is a close approximation of the new cup holders. It was a great triumph for the club, but also for the country. As for the squad… nothing really can be said. May be the only thing of real import was the coming of sponsorship to Africa – in this case, the deodorant firm Old Spice. The international victory was important in another sense too – Al-Ahly was the strongest Egyptian club – since the establishment of the national championship in 1949, they won 17 titles (including 1982) in the 26 championships played. Such strong tradition needed international success and at last Al-Ahly got it.

This is picture of Al-Ahly in 1981, which at least is a close approximation of the new cup holders. It was a great triumph for the club, but also for the country. As for the squad… nothing really can be said. May be the only thing of real import was the coming of sponsorship to Africa – in this case, the deodorant firm Old Spice. The international victory was important in another sense too – Al-Ahly was the strongest Egyptian club – since the establishment of the national championship in 1949, they won 17 titles (including 1982) in the 26 championships played. Such strong tradition needed international success and at last Al-Ahly got it.