The UEFA Cup. Perhaps one of the most intriguing issues of the tournament. First of all, no English, Spanish, and Italian club reached the third round. To a point, fate played a role, the draw opposing teams from the top football leagues early. But it was not just poor luck – the decline of the leading nations was noticeable for some time. Thus, there were few upsets: Carl Zeiss (DDR) won both legs against West Bromwich Albion and Dynamo Dresden (DDR) also did so against Atletico Madrid in the first round. In the second round Universitatea Craiova (Romania) eliminated Leeds United, winning both legs 2-0. The results were unusual, but hardly front page news: Atletico Madrid and Leeds United were in decline; WBA – not really strong. The tournament manifested the leading position of West German football in a very special way: West Germany had 5 participants this year and all of them reached the ¼ finals – only at this stage elimination of one German team became inevitable, for at least one pair had to be between Germans. The draw was favourable and as a result the ½ finals were entirely German – for the first time the last 4 teams represented one country. Luck was on German side, but there was no doubt about the quality of the teams: they eliminated whoever they played with.

The other memorable event was the great run of the modest Bulgarian Lokomotiv (Sofia). In the first round they faced Ferencvaros (Budapest) and eliminated the Hungarians 3-0 and 0-2. Lokomotiv faced Monaco in the 1/16 finals and won 4-2 and 1-2. The matches with Monaco instantly became a legend – Lokomotiv’s star Atanas (Nachko) Mikhailov scored all 5 goals. For this he was nicknamed Monachko – a pun, combining the name of the opponents and the name fans used to call him lovingly: Mo-nachko. But this was still nothing – in the 1/8 finals Lokomotiv was paired with Dinamo (Kiev). To all, it was the end: Dinamo, although not great, was overwhelming favourite, but political arguments weighted more than purely football ones. In Bulgaria, everybody was certain that Lokomotiv will be ordered to lose without a fight. Already Dinamo played against Bulgarian team – in the first round they met CSKA (Sofia) and eliminated the strongest Bulgarian team 2-1 and 1-1. The results were misleading: Dynamo was far from great, but CSKA made sure that Kiev will go ahead. It was not for the first time and it was taken for granted that Bulgarian team will put no resistance against Soviet club. So, the first leg was surprising: Lokomotiv won 1-0 in Sofia. Nachko Mikhailov scored from free kick – his trade-mark. Still, nobody believed in final victory. The advantage was fragile, the referee for the second leg was Hungarian, and Dynamo was objectively the stronger squad. Lokomotiv had fair chance against earlier opponents: Ferencvaros and Monaco played football suitable for Lokomotiv – technical and relatively slow. Both teams had no great stars. Dynamo was entirely different: fast, physical, domineering the field. Lokomotiv’s defensive style, based on slower tempo, allowing the opponents to attack was not going to work against such an opponent: Lokomotiv depended on counter-attacks left to the imagination of Nachko Mikhailov, who was fat, slow, and too egoistic most of the time – it was clear that the Soviets will shadow him closely and block his individual efforts. So was expected, although the first leg already showed that Dynamo was not really able to stop one of the all-time best Bulgarians. The match in Kiev crushed wisdom, certainties, and expectations. Lokomotiv surprised everyone, including Dynamo’s players, with fighting spirit. Dynamo attacked, but they were lacking imagination and this helped the defensive style of Lokomotiv. With time, surprise changed to frustration: Dynamo realized they were facing determined and concentrated foe, not at all giving up. Since Lobanovsky was ruthless coach, the match turned ugly – the Soviets tackled fiercely and dangerously and the referee just allowed brutality. If the match was played today, it would be over by half-time, for Dynamo would have too many players send off to continue. But back at the end of the 1970s there was no problem with players clearly looking to break the legs of the opponents. Still, Dynamo scored 2 goals in the first half and looked like they will win, however unjustly. Lokomotiv retaliated to the brutal approach and eventually Khapsalis (Dinamo) and Stoykov (Lokomotiv) were sent off. After the match Soviet commentators lamented the expulsion of Khapsalis, for he was the most dangerous striker of their team at the moment (Blokhin just came back from injury and not at his best yet), but a quick look at the other side tells different story: the referee was blind only to Soviet brutality and provocations – he showed 3 yellow cards to Bulgarian players (Arsov, Dimitrov, and Vassilev) and expelled Dimitrov for second offense. He and Stoykov were the central defenders of Lokomotiv and both were send off, thus opening a big gap. Khapsalis was expelled only because of the fight between him and Stoykov – there was no option, but to expel both. Not a single Soviet player was carded for his own offenses, some of which were gruesome. Yet, Lokomotiv fought bravely and in the 70th minute Nachko Mikhailov had the ball. He saw the opportunity, quickly made a long pass to the only Bulgarian in Dinamo’s half of the field, Nako Doychev, who replaced the right full-back Zhelev in the 31st minute. The young striker made a mighty kick from a great distance and scored. 2-1. To the end of the match Dynamo attacked fruitlessly. Lokomotiv won, thanks to their away goal. It was unbelievable, but true.

Lokomotiv had little chances for the ¼ finals – 5 West German teams, Saint Etienne, and Zbrojovka (Brno). Only the Czechoslovaks were beatable opponent, but Lady Luck was not on Bulgarian side – the draw paired them with Stuttgart. In the euphoria, following the great victory over Dinamo (Kiev), Stuttgart was perceived as a beatable opponent. Bulgarian observers were quite wrong in their estimation: Stuttgart was not strong during the 1970s, but at the moment was up and coming team. The fairy-tale ended – the Germans were superior and easily eliminated Lokomotiv 3-0 and 1-0. Unfortunately, Lokomotiv had limited squad and there were no replacements of the key players suspended after the match in Kiev. No matter – it was fantastic run, still remembered and praised. Remembered not only for what happened on the pitch, but also for what happened in the aftermath of the epic battle with Dynamo (Kiev).

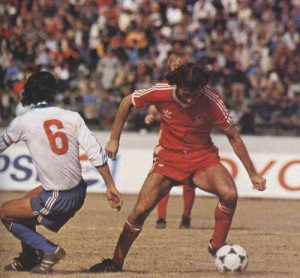

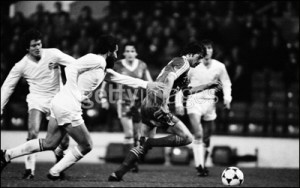

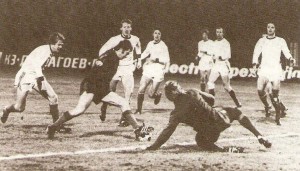

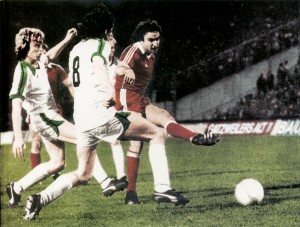

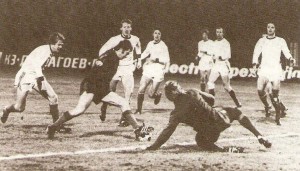

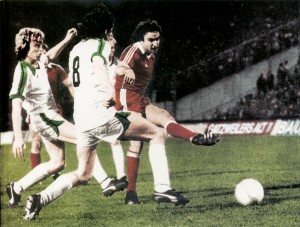

Nachko Mikhailov at his best. Lokomotiv was the underdog against Dinamo, but… Nachko is surrounded by Bessonov, Kolotov, Konkov, Romensky, Buryak, Veremeev, and Berezhnoy, and they are unable to stop him. Bessonov, personal marker of Mikhailov, is left behind. No wonder the Soviet stars were increasingly frustrated. As for Nachko – perhaps this was his greatest season: 5 goals in the net of Monaco; a winning goal in the home leg against Dinamo, and the great pass to Doychev, who scored in Kiev. As for Bessonov… well, he left his mark on the legs of Nachko, who was unable to walk after the second match.

Nachko Mikhailov at his best. Lokomotiv was the underdog against Dinamo, but… Nachko is surrounded by Bessonov, Kolotov, Konkov, Romensky, Buryak, Veremeev, and Berezhnoy, and they are unable to stop him. Bessonov, personal marker of Mikhailov, is left behind. No wonder the Soviet stars were increasingly frustrated. As for Nachko – perhaps this was his greatest season: 5 goals in the net of Monaco; a winning goal in the home leg against Dinamo, and the great pass to Doychev, who scored in Kiev. As for Bessonov… well, he left his mark on the legs of Nachko, who was unable to walk after the second match.

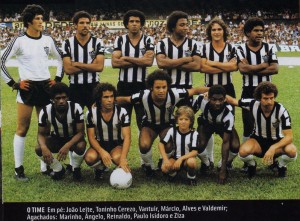

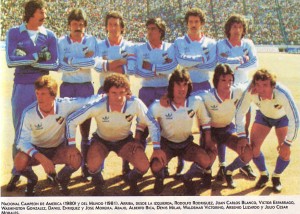

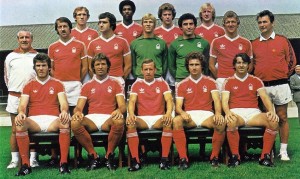

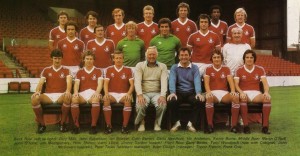

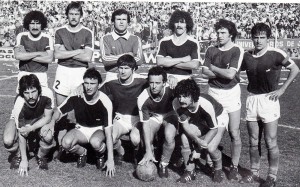

Lokomotiv (Sofia) 1979-80. Third row from left: A. Elenkov, G. Stankov, R. Goranov, Y. Stoykov, N. Donev, N. Zhelev, G. Bonev.

Lokomotiv (Sofia) 1979-80. Third row from left: A. Elenkov, G. Stankov, R. Goranov, Y. Stoykov, N. Donev, N. Zhelev, G. Bonev.

Middle row: V. Metodiev – coach, T. Sokolov, K. Petkov, B. Velichkov, A. Kolev, N. Spassov, N. Doychev, D. Donkov – assistant coach.

Crouching: A. Mikhailov, I. Vassilev, B. Dimitrov, V. Arssov, I. Dangov, G. Stefanov.

A nice, but limited squad, immediately presenting the predicament of small clubs: A. Mikhailov, R. Goranov, T. Sokolov, G. Bonev, Y. Stoykov, A. Kolev, B. Dimitrov, and V. Arssov were well known Bulgarian players of whom only V. Arssov did not play for the national team. But they were regulars since 1971 and 30 years old at the end of the decade. Behind them only two players were becoming stars – B. Velichkov and N. Donev. Young talent was also scarce – N. Zhelev and N. Doychev. Experienced, but getting too old first team and no strong reserves. Actually, no back-ups at some posts at all – no other central defenders than Stoykov and B. Dimitrov, for instance. But Lokomotiv had great coach – perhaps the best ever Bulgarian coach – Vassil Metodiev. He utilized his limited resources in full and was excellent tactician and motivator. He made Lokomotiv champions in 1978 and was the instrumental for their great run in the UEFA Cup. Yet, this was the swan song of the aging squad – Metodiev achieved more than ever dreamed, for on top of having short and limited team, he had to improvise constantly: for instance, Sokolov was suspended and unable to play against Dinamo. The full back Stefanov took his place in midfield. After the second leg with Dinamo Dimitrov and Stoykov were suspended too and against Stuttgart Lokomotiv had no central defenders at all. But this was nothing compared to other punishments and misfortunes following the elimination of Dinamo (Kiev). Beating a Soviet team was not taken lightly – the Communist Party (not the club!) sacked Vassil Metodiev immediately. He was blacklisted for years and few years later, when coaching Levsky-Spartak and eliminated same Dinamo (Kiev) again, troubles and punishments followed again. Nothing was said at the time, but the speedy winger Ivan Dangov was more than injured by Dynamo players: everybody saw the viscious tackle after which Dangov had to be replaced in the second leg, but nobody saw what happened next: Dangov’s testicles were sliced and had to be removed. After facing Lobanovsky’s stars, Dangov ended an eunuch… The player was unable to come in terms with losing his manhood and committed suicide. Somehow, the great success of Lokomotiv doomed the heroes: Boko Dimitrov died stone-deaf and in extreme poverty. Nachko Mikhailov’s fate was not nice either. Almost all players were quickly forgotten after their retirement from the game. Such were the times… the ruling Communists considered football part of politics and elimination of Soviet team was practically equal to anti-Communist statement, a political crime almost.

At the ¼ finals the first West German casualty came at last: 1. FC Kaiserslautern was beaten by Bayern 1-0 and 1-4. Well, one had to be eliminated here. The rest of the West German teams had no problems – Stuttgart won both legs against Lokomotiv (Sofia) and so did Borussia (Moenchengladbach) against Saint Etienne. Only Zbrojovka (Brno) managed to win against Germans, but it was too late – after losing 1-4 in Frankfurt, the Czechs won 3-2 at home for consolation. Historic semi-finals followed: all participants from one country. The opponents knew each other more than well, had no inhibitions, but great ambitions, and played the same kind of football. A lot was at stake, for the opponents had long history behind them to spur desires, to settle scores, to take revenge, and simply to win. Everything was decided on home turf and the second leg was actually decisive: hosts won the first leg – Stuttgart – Borussia 2-1, and Bayern – Eintracht 2-0. The second leg the losers just put aside caution and rushed ahead. Borussia’s win – 2-0 – was more or less expected. Eintracht’s, however, was less so and if it was, not by such result: they destroyed Bayern 5-1. True, it was not an easy victory, but took extra time after the regular match finished 2-0. Eintracht and Borussia reached the final.

Borussia went to its 4th UEFA Cup final – so far, they won the Cup twice, the second time in the previous year. One of the best clubs of the 1970s, Borussia had the experience and also the desire to add one more trophy to its collection. Eintracht never won European trophy and played a final only once – in 1960, when they lost to Real (Madrid) 3-7 the final for the European Champions Cup. History is history, but German teams have enough motivation anyway and a battle between two German teams is extremely competitive. Perhaps Borussia was a bit in disadvantage – hard to say why today, but they hosted Eintracht at their own stadium,which is small. Normally, Borussia plays important matches at bigger stadiums in nearby cities to provide room for more supporters. Important or not, the difference is great: Borussia played in front of 25 000 at home and in front of 59 000 in Frankfurt. The ’12th player’ was numerous and very loud in the second leg, but was not supporter of Borussia. On the pitch, it was German business as usual – fast, attacking, uncompromising, physical football.

Who will win? The 1974 World champion or the guy who never played for West Germany? The world champion never won a German title or an international club trophy. The second-rater had a few German titles and two UEFA cups already.

Who will win? The 1974 World champion or the guy who never played for West Germany? The world champion never won a German title or an international club trophy. The second-rater had a few German titles and two UEFA cups already.

Final 1st Leg, Bökelberg, Moenchengladbach, 7 May 1980, att 25000

Borussia M’gladbach (1) 3 Eintracht Frankfurt (1) 2

37′ 0-1 E: Karger

44′ 1-1 B: Kulik

71′ 1-2 E: Hoelzenbein

76′ 2-2 B: Matthaeus

88′ 3-2 B: Kulik

Borussia M’gladbach

Kneib; Hannes, Schäfer, Schäffer, Ringels; Matthäus, Kulik, Nielsen(Thychosen); Del’Haye (Boedeker), H.Nickel, Lienen

Eintracht Frankfurt

Pahl; Pezzey, Neuberger, Körbel, Ehrmanntraut; Lorant, Hölzenbein(Nachtweih), Borgers, B.Nickel; Cha, Karger (Trapp)

Final 2nd Leg, Mainstadion, Frankfurt, 21 May 1980, att 59000

Eintracht Frankfurt (0) 1 Borussia M’gladbach (0) 0

81′ 1-0 E: Schaub

Eintracht Frankfurt

Pahl; Pezzey, Neuberger, Körbel, Ehrmanntraut; Lorant, Hölzenbein, Borgers, B.Nickel; Cha, Nachtweih (Schaub)

Borussia M’gladbach

Kneib; Boedeker, Hannes, Schäfer, Ringels; Matthäus (Thychosen),Fleer, Kulik, Nielsen (Del’Haye); H.Nickel, Lienen

Borussia won the home leg with difficulty – 3-2, after Eintracht had twice the advantage. Interestingly, Borussia scored two goals at the very end of the playing time – equalizer in the 44th minute of the first half, and the winning goal in the 88th minute. Kulik scored both goals – no wonder he was captaining Borussia. The second leg was similarly equal, but Eintracht was tiny bit more dangerous in attack. The only goal came late – the substitute Schaub scored in 81st minute. A goal is a goal, but one could blame Borussia’s defense, which was often shaky anyway. Kneib was not quick enough to react – unfortunate, but typical problem of very tall goalkeepers, when the ball is low and goes to the corner of the net. Anyway, Eintracht scored the winning goal and the Cup was theirs after a tough final.

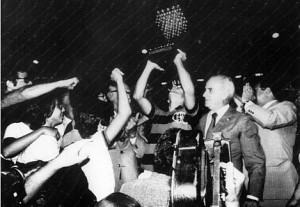

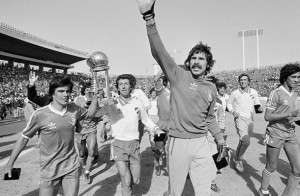

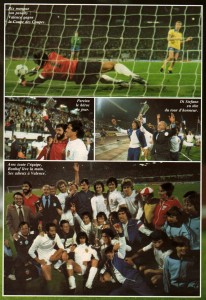

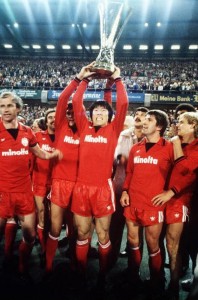

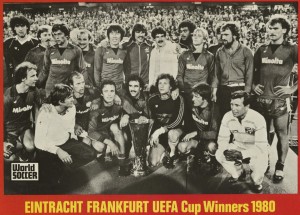

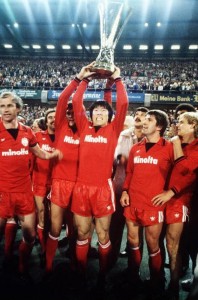

A great picture of the new winners – Bum Kun Cha triumphal with the UEFA Cup, but this is a strange photo: shirt advertisement was still banned in the international tournaments and the finalists played with plain shirts. Yet, the winners appear with their usual domestic kit:

A great picture of the new winners – Bum Kun Cha triumphal with the UEFA Cup, but this is a strange photo: shirt advertisement was still banned in the international tournaments and the finalists played with plain shirts. Yet, the winners appear with their usual domestic kit:

Great moment indeed – Eintracht with well deserved first European trophy. First and… so far last. In the real time, it was wonderful to see a new winner. In retrospect, it was the end of an era – both finalists were already in decline. Neither will be ever the same, both stepping down from leading positions. The 1980 final was a victory of the old guard – the new Bayern and the up and coming Stuttgart were not fully ready to rule and were eliminated in the ½ finals by teams already going down, but still strong enough. The sad truth was that neither UEFA Cup finalist represented something fresh.

Great moment indeed – Eintracht with well deserved first European trophy. First and… so far last. In the real time, it was wonderful to see a new winner. In retrospect, it was the end of an era – both finalists were already in decline. Neither will be ever the same, both stepping down from leading positions. The 1980 final was a victory of the old guard – the new Bayern and the up and coming Stuttgart were not fully ready to rule and were eliminated in the ½ finals by teams already going down, but still strong enough. The sad truth was that neither UEFA Cup finalist represented something fresh.

Borussia, although a worthy finalist, failed to win a third UEFA Cup. Perhaps rightly so – it was no longer the exciting team of the early 1970s. Inevitably, the great stars stepped down and now former reserves and mere supporting players lead the team: Kulik, Nickel, Danner, Hannes, Klinkhammer. The current star was Del’Haye – a player, who never came even close to his predecessor Heynckes. The sad truth was that Borussia was lead by second-raters, easily confirmed – the current leaders were not national team players. They were determined, fit, eager, but lacked finesse and imagination. The finals showed the players’ limitations: Del’Haye disappointed in the first leg, was replaced, and did not start the second leg (but came out nevertheless, replacing Nielsen). Lothar Matthaus, the brightest new German hope, had to be substituted by Tychosen (himself still not good enough for regular place in the team). The defense was shaky and there was no player even approximately similar to Vogts. Kulik was the best player, at least in the final, but he was not Wimmer, and there was no point even mentioning Netzer. Lienen, the best and most dangerous striker in the second leg of the final, was more determined and willing left-winger than really dangerous. Heynckes scored plenty of goals – Lienen did not and it was even difficult to imagine him scoring. It was team going down, not up… Matthaus was soon to leave and there was nobody else. Even Heynckes was not impressive – the young coach did not show anything inspiring yet: his team was quite predictable in tactics and style. The era of Borussia was closing, that was sure. And Borussia somewhat never fulfilled the expectations – they were one of the top teams in the 1970s, but never reached the top, never dominated the European scene.

Borussia, although a worthy finalist, failed to win a third UEFA Cup. Perhaps rightly so – it was no longer the exciting team of the early 1970s. Inevitably, the great stars stepped down and now former reserves and mere supporting players lead the team: Kulik, Nickel, Danner, Hannes, Klinkhammer. The current star was Del’Haye – a player, who never came even close to his predecessor Heynckes. The sad truth was that Borussia was lead by second-raters, easily confirmed – the current leaders were not national team players. They were determined, fit, eager, but lacked finesse and imagination. The finals showed the players’ limitations: Del’Haye disappointed in the first leg, was replaced, and did not start the second leg (but came out nevertheless, replacing Nielsen). Lothar Matthaus, the brightest new German hope, had to be substituted by Tychosen (himself still not good enough for regular place in the team). The defense was shaky and there was no player even approximately similar to Vogts. Kulik was the best player, at least in the final, but he was not Wimmer, and there was no point even mentioning Netzer. Lienen, the best and most dangerous striker in the second leg of the final, was more determined and willing left-winger than really dangerous. Heynckes scored plenty of goals – Lienen did not and it was even difficult to imagine him scoring. It was team going down, not up… Matthaus was soon to leave and there was nobody else. Even Heynckes was not impressive – the young coach did not show anything inspiring yet: his team was quite predictable in tactics and style. The era of Borussia was closing, that was sure. And Borussia somewhat never fulfilled the expectations – they were one of the top teams in the 1970s, but never reached the top, never dominated the European scene.

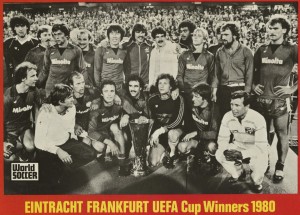

The brand new UEFA Cup winners: third row, from left: Hübler – trainer, Grabowski, Nickel, Lorant, Borchers, Karger, Schaub, Nachtweih, Hölzenbein, Schmidt-Rönnau – masseur.

The brand new UEFA Cup winners: third row, from left: Hübler – trainer, Grabowski, Nickel, Lorant, Borchers, Karger, Schaub, Nachtweih, Hölzenbein, Schmidt-Rönnau – masseur.

Middle row: Rausch – coach, Von Thümen – Président, Schulte – assistant coach, Lottermann, Körbel, Gruber, Pezzey, Trapp, Cha Bum, Ehrmantraut, Arda – condition trainer, Klug -Manager.

Sitting: Neuberger, Funk, Pahl, Müller.

Well deserving winners, no doubt – Eintracht was the slightly better team at the finals. More balanced and more dangerous. But… they were also a team of the past. Grabowski was no longer playing. Holzenbein was getting old. Gone were the times when Eintracht was expected to become the third great West German team, equal to Bayern and Borussia. A few spectacular international failures happened – Eintracht did not live up to expectations and, with time, it became clear that they will not have great selection. By the end of the 1980s Eintracht, like Borussia, run on inertia. Korbel was rapidly becoming the symbol of the club – sturdy, reliable, fit, yet, never a true star. His few appearances for the national team were already in a distant past. For Nickel, Lorant, Borchers one thing was sure – they were not going to be at the level of Grabowski and Holzenbein. More like Korbel – dependable second-raters. And the East German refugees Pahl and Nachtweih were not to be superstars either. Yet, Eintracht had two great players – the Austrian libero Pezzey, one of the best in the world at the time, dubbed ‘the new Beckenbauer’, and the exciting South Korean striker Bum Kun Cha. Cha was especially dangerous in the second leg against Borussia, clearly making the difference between winners and losers. The Korean was seen more as a novelty at that time – the first South Korean player to play in West Germany and Europe, and the second Asian to shine in the Bundesliga, after the Japanese striker Okudera won the Bundesliga with Koln in 1978. Bum Kun Cha arrived in 1978 and joined Darmstadt 98 – he played a single match for them, not a great beginning. However, Eintracht saw his potential and sighed him in 1979 – Cha delivered, quickly becoming a key player of the team and a Bundesliga star. Having two great players was not enough, unfortunately – Eintracht was slowly going downhill. Winning the UEFA Cup was great, but in a way, a victory coming too late. It was a closing of an era, closing of the 1970s football. Yet, winners are winners and in the final Eintracht was the more convincing team. Too bad Grabowski was not playing…

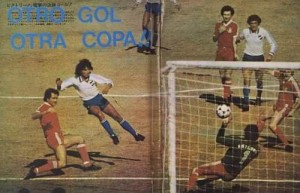

Fred Schaub, the little known young substitute, scores the winning goal for Eintracht.

Fred Schaub, the little known young substitute, scores the winning goal for Eintracht.

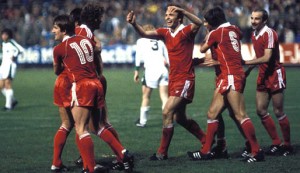

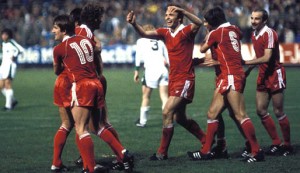

Happy Eintracht after the goal. Observe their shirts – no adds, as regulated by UEFA.

Happy Eintracht after the goal. Observe their shirts – no adds, as regulated by UEFA.

Big change is coming! No, no the way the game is played, but how it is represented. Bruno Pezzey is still dressed in his plain playing shirt. His teammate holds the UEFA Cup in new shirt, displaying the name of the sponsor – Minolta. Erosion of the rules… yes, they have to play in plain shirts, but after the match? When shirts are exchanged with the other team or thrown to the delighted crowd, or are just too wet to wear? Rules say nothing about the time after the match – and Eintracht posed in their usual shirts with the name of their sponsor. And soon UEFA will give up. The 1980s started.

Big change is coming! No, no the way the game is played, but how it is represented. Bruno Pezzey is still dressed in his plain playing shirt. His teammate holds the UEFA Cup in new shirt, displaying the name of the sponsor – Minolta. Erosion of the rules… yes, they have to play in plain shirts, but after the match? When shirts are exchanged with the other team or thrown to the delighted crowd, or are just too wet to wear? Rules say nothing about the time after the match – and Eintracht posed in their usual shirts with the name of their sponsor. And soon UEFA will give up. The 1980s started.

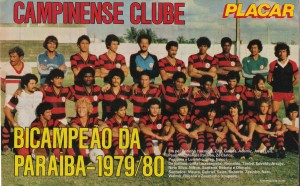

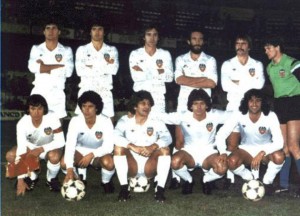

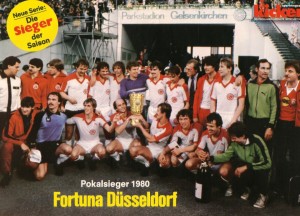

Club Atletico Sarmiento (Junin) won the Second Division and was promoted. A little known club, usually called just Sarmiento, it was found in 1911 and never played top level football. Winning the Second Division was their biggest success so far.

Club Atletico Sarmiento (Junin) won the Second Division and was promoted. A little known club, usually called just Sarmiento, it was found in 1911 and never played top level football. Winning the Second Division was their biggest success so far. New champions: standing from left: Glaría, Peremateu, Hernandorena, Romero, Polo, Espósito.

New champions: standing from left: Glaría, Peremateu, Hernandorena, Romero, Polo, Espósito. This very season Platense managed to dress its players with unmatching jerseys for a championship game. But let stay with Sarmiento: no famous players here and perhaps little chances for survival among the best, but it was wonderful season for the boys and their fans. May be even for the whole town, for Junin had no first division team at the moment.

This very season Platense managed to dress its players with unmatching jerseys for a championship game. But let stay with Sarmiento: no famous players here and perhaps little chances for survival among the best, but it was wonderful season for the boys and their fans. May be even for the whole town, for Junin had no first division team at the moment.