The First Division was divided into three groups during 1979-80 season – 2 outsiders, two favourites, running head to head to the end, and between the lowest and the highest vast fairly equal bulk, almost a league by itself. 13 points separated the bronze medalist from the third relegated team at 16th place. 13 points also separated bronze from silver…

Malaga was last with 19 points.

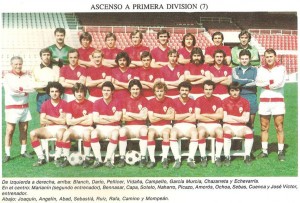

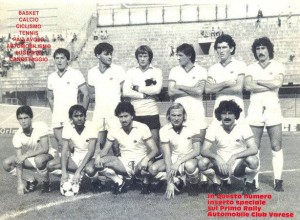

Standing, from left:Burgueña,Orozco,Brescia,Cantarutti,Viberti,x,x,Mesquida,x,Corral,Popo,Nacho,Muñoz Pérez; Middle row:Javi,Aido,Migueli,Vargas,Salguero,Santi;

Standing, from left:Burgueña,Orozco,Brescia,Cantarutti,Viberti,x,x,Mesquida,x,Corral,Popo,Nacho,Muñoz Pérez; Middle row:Javi,Aido,Migueli,Vargas,Salguero,Santi;

Sitting:Salcedo,Castro,Juan Carlos,Astorga,Alcaide?,Macías,Aráez,Filgueira,Collantes,Martín.

To a point, Malaga was largely a warning for the newly promoted: promoted in 1978-79, relegated in 1979-80. The longest time Malaga played in Primera was 5 consecutive seasons. Normally, they lasted a year or two. They were hopelessly last, finishing with fewer points than they actually earned: 3 points were deducted as a penalty for forfeiting their match against AD Almeria.

Thanks to the deducted points, Burgos CF finished 19th. They were really the worst team team this year, earning just 20 points.

The only thing to say about Burgos has nothing to do with their pathetic season, but about their history and that only from contemporary standpoint. Burgos was found in 1922 as Gimnastica Burgalesa Club de Futbol. In 1948 the name was changed to Burgos Club de Futbol and under this name they reached and played their bit in the top Spanish league. But today the club has two foundational years – 1922 and 1994 and this is because they disappeared in 1983 due to grave financial problems. Their reserve team – Burgos Promesas – was renamed Real Burgos Club de Futbol and played under this name until 1993, when once again the club was bankrupt and dissolved. Only to be refounded again as Burgos Club de Futbol. The painfully familiar scheme of preserving a club without paying mounting debts, leading to historic confusion. Arguments are pointless – if only Burgos was not relegated in 1980, money would not have been a problem; if money was not a problem, they would have been outsiders in 1979-80. Which came first – the chicken or the eggs?

Unlike the two outsiders, the third relegated club fought to the end and lost the battle for survival.

Unlike the two outsiders, the third relegated club fought to the end and lost the battle for survival.

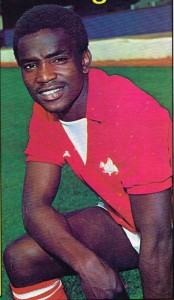

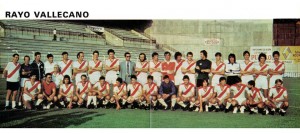

Dwarfed by its giant neighbours – Atletico and Real – Rayo Vallecano is the third significant club in Madrid, but the world was largely unaware of its existence until 1976-77, when Rayo Vallecano won promotion for the first time. Modest and somewhat restricted to its own neighbourhood, Vallecas, Los Franjirrojos (the Red Sashes) is almost a club from another city: nobody seriously considers a match between them and the big two a derby. And so big are the neighbours, Rayo Vallecano never managed to elevate itself from its insignificant predicament. Going to Primera in 1977 was their biggest success since founded in 1924. Staying in Primera was almost heroic achievement, but the Cindarella story ended in 1979-80. They fought as much as they could, but at the end were 2 points short – Hercules (Alicante) survived with 28 points – Rayo finished with 26 and unlucky 16th. No surprise, really. They had only one great player – Fernando Morena. The Uruguayan star delivered what he was hired for – 20 goals – but he was the only strong player in the team and his performance was not enough to save the club. Rayo Vallecano went down to its familiar second division apparently for good.

Dwarfed by its giant neighbours – Atletico and Real – Rayo Vallecano is the third significant club in Madrid, but the world was largely unaware of its existence until 1976-77, when Rayo Vallecano won promotion for the first time. Modest and somewhat restricted to its own neighbourhood, Vallecas, Los Franjirrojos (the Red Sashes) is almost a club from another city: nobody seriously considers a match between them and the big two a derby. And so big are the neighbours, Rayo Vallecano never managed to elevate itself from its insignificant predicament. Going to Primera in 1977 was their biggest success since founded in 1924. Staying in Primera was almost heroic achievement, but the Cindarella story ended in 1979-80. They fought as much as they could, but at the end were 2 points short – Hercules (Alicante) survived with 28 points – Rayo finished with 26 and unlucky 16th. No surprise, really. They had only one great player – Fernando Morena. The Uruguayan star delivered what he was hired for – 20 goals – but he was the only strong player in the team and his performance was not enough to save the club. Rayo Vallecano went down to its familiar second division apparently for good.

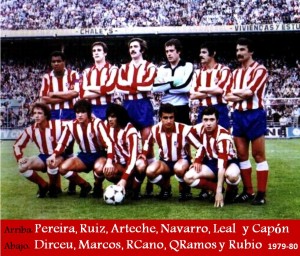

This was not a great year for another club from Madrid – Atletico had miserable season. They finished 13th with 31 points. Five points ahead of minuscule Rayo Vallecano, but 22 points behind Real. If Rayo Vallecano escaped relegation, may be they would have been proud to be on similar level with Atletico, but from the other point of view it was only shame: to be compared to Rayo was a disgrace.

Sinking so low seemed illogical: Luis Aragones, already successful and respected, was coaching them. The squad was strong, as far as names, one more Brazilian star was added to Luis Pereira – Dirceu, no less. But the crisis is understandable: Atletico aged as a team. No radical changes were made for a long time – only small additions. Some key players left (Leivinha) or were too old to make a difference (Ayala). Luis Pereira was beyond his peak and Dirceu did not fit well for whatever reason. Atletico needed a new squad, a full rebuild. The season should have been a wake-up call – a bit too late may be, but much needed.

Sinking so low seemed illogical: Luis Aragones, already successful and respected, was coaching them. The squad was strong, as far as names, one more Brazilian star was added to Luis Pereira – Dirceu, no less. But the crisis is understandable: Atletico aged as a team. No radical changes were made for a long time – only small additions. Some key players left (Leivinha) or were too old to make a difference (Ayala). Luis Pereira was beyond his peak and Dirceu did not fit well for whatever reason. Atletico needed a new squad, a full rebuild. The season should have been a wake-up call – a bit too late may be, but much needed.

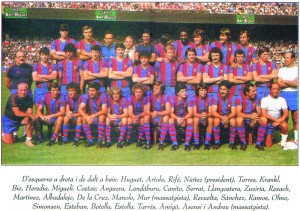

The other club in need of waking call was Barcelona – they finished 4rd, but far behind the leading clubs. Since the real measure for Barcelona is only Real Madrid, the red signal for danger was flashing: Barcelona ended with 15 points less than their arch-enemy and Real was not particularly great . Barcelona suddenly found itself in unlikely company – similar to Sporting Gijon, Real Betis, Salamanca, and Almeria.

Like Atletico Madrid, Barcelona needed radical rebuilding – they kept a cluster of players too long. There were problems unsolved for years – particularly goalkeeping. Asensi and Rexach were getting too old. Krankl and Simonsen presented a problem for the future – they were both strikers, but the team needed a defender and a playmaker to organize a new team around them. Which meant that both foreigners were not going to last, for they represented to a point the old guard. At least one of them was to be out soon to open space for a foreign midfielder. A good goalkeeper had to be found – and quickly.

Like Atletico Madrid, Barcelona needed radical rebuilding – they kept a cluster of players too long. There were problems unsolved for years – particularly goalkeeping. Asensi and Rexach were getting too old. Krankl and Simonsen presented a problem for the future – they were both strikers, but the team needed a defender and a playmaker to organize a new team around them. Which meant that both foreigners were not going to last, for they represented to a point the old guard. At least one of them was to be out soon to open space for a foreign midfielder. A good goalkeeper had to be found – and quickly.

The weakness of the usual strong clubs – Barcelona, Atletico Madrid, Valencia, Athletic Bilbao, Sevilla, Real Zaragoza – suddenly elevated smaller clubs.

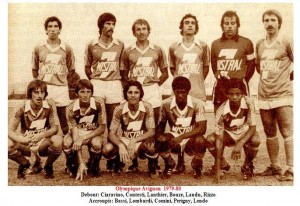

The league debutante Almeria finished 10th. Excellent season for almost anonymous club. Of course, they benefited by the weakness of the traditionally strong, but never mind. The team depended on 5 South Americans – the typical for Spanish clubs combination of Argentines (Daniel Pavon and Ricardo Martinez), Paraguayans ( Rolon and Oscar Lopez), and the odd Brazilian (Odair). Some of them were surely oriundi – to have that many foreign players did not make sense otherwise.

The league debutante Almeria finished 10th. Excellent season for almost anonymous club. Of course, they benefited by the weakness of the traditionally strong, but never mind. The team depended on 5 South Americans – the typical for Spanish clubs combination of Argentines (Daniel Pavon and Ricardo Martinez), Paraguayans ( Rolon and Oscar Lopez), and the odd Brazilian (Odair). Some of them were surely oriundi – to have that many foreign players did not make sense otherwise.

Salamanca finished 9th , a point better than Almeria. The big star of this vintage was a newcomer – the Paraguayan striker Carlos Diarte, who arrived from Valencia. Diarte never achieved European fame, but in Spain he was a star – one of the first crop of foreigners, he arrived in 1973, when he was just 19-year old.

Salamanca finished 9th , a point better than Almeria. The big star of this vintage was a newcomer – the Paraguayan striker Carlos Diarte, who arrived from Valencia. Diarte never achieved European fame, but in Spain he was a star – one of the first crop of foreigners, he arrived in 1973, when he was just 19-year old.

Real Betis ended 5th , 2 points behind Barcelona. Up and down club, but this season clearly up and once again coming on top of their rivals Sevilla.

Real Betis ended 5th , 2 points behind Barcelona. Up and down club, but this season clearly up and once again coming on top of their rivals Sevilla.

Yet, none of the clubs above was really rising – they simply had a good season, most likely not to be repeated. The rising clubs were two: Sporting Gijon and Real Sociedad.

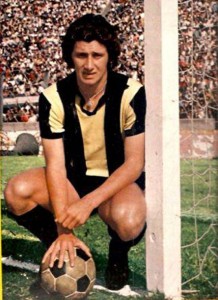

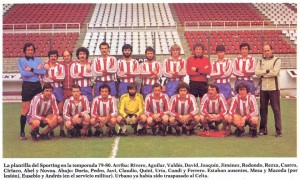

Sporting Gijon bettered Barcelona by a point and got the bronze medals. Gijon jumped from 14th place the previous season to 3rd, leaving for the first time the lower half of the table. The team was not made of famous players, but it was sturdy, well rounded, and lead by a big star – Quini. Enrique Castro, known as Quini, was already the top Spansih striker and a goal-scoring machine. He was the top scorer of the league this year with 24 goals. In attack, Quini was helped by newly added Aguilar, who had been a starter of Real Madrid for years. The formula was good in general: individually, the players were not so great to attract the appetites of the big clubs. Sporting was strong as a team, but there was a question mark: Quini. It all depended on how long he will stay with the club – of he moved the scheme was liable to collapse. And the danger was real: Sporting had no means to keep a superstar. Thus, Sporting Gijon was up and coming, but continued rise depended largely on Quini.

Sporting Gijon bettered Barcelona by a point and got the bronze medals. Gijon jumped from 14th place the previous season to 3rd, leaving for the first time the lower half of the table. The team was not made of famous players, but it was sturdy, well rounded, and lead by a big star – Quini. Enrique Castro, known as Quini, was already the top Spansih striker and a goal-scoring machine. He was the top scorer of the league this year with 24 goals. In attack, Quini was helped by newly added Aguilar, who had been a starter of Real Madrid for years. The formula was good in general: individually, the players were not so great to attract the appetites of the big clubs. Sporting was strong as a team, but there was a question mark: Quini. It all depended on how long he will stay with the club – of he moved the scheme was liable to collapse. And the danger was real: Sporting had no means to keep a superstar. Thus, Sporting Gijon was up and coming, but continued rise depended largely on Quini.

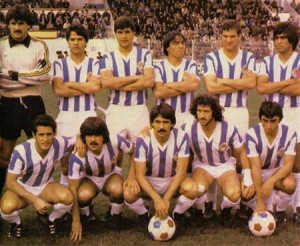

The other ascending club was entirely different: Real Sociedad had an young and very talented generation, almost entirely home-made. The bright youngsters were still only hopefuls, so they were not yet a target for the big clubs. But they were going up and there was no doubt that this squad will be a decisive factor in Spanish football very soon. Real Sociedad run for the title this season and lost it by a point. They lost only one match! They also had the best defensive record by far – Real Sociedad allowed only 20 goals. Real Madrid and Barcelona shared the second best record, receiving 33 goals each.

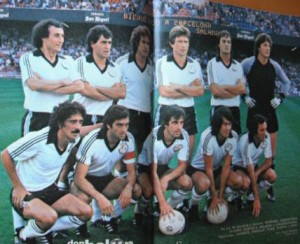

![]()

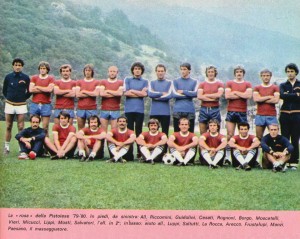

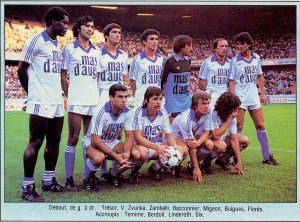

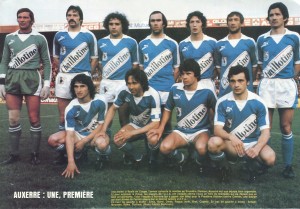

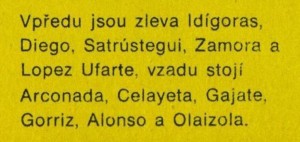

The club from San Sebastian had their best season ever, but still the feeling was that this achievement will be outdone soon. So far, Lopez Ufarte and Zamora were recognized as almost full-fledged stars, but already the big name – and captain of the team – was the goalkeeper Arconada. He debuted in 1973 and by now was experienced, yet still young – just 26 years old, which for goalkeepers is not even the peak. No wonder Real Sociedad received so few goals – Arconada was rapidly becoming one of the best European goalkeepers. Perhaps luckily for the club, Arconada appeared when the big clubs had the previous generation of solid keepers still playing well (Iribar, Reina, Sadurni). By 1979-80 the veterans were gone, those of the immediate next generation aged (Garcia Remon and Miguel Angel), Arconada was national team regular, and Real Sociedad was rising – no point to go elsewhere. And he did not – he was in the right club at the right time. His greatest years coincided with the greatest years of Real Sociedad. The best was still to come. As for the picture, Real Sociedad here is dressed in their second kit – since their usual colours will fly for quite some time, let see their lesser known second option.

The club from San Sebastian had their best season ever, but still the feeling was that this achievement will be outdone soon. So far, Lopez Ufarte and Zamora were recognized as almost full-fledged stars, but already the big name – and captain of the team – was the goalkeeper Arconada. He debuted in 1973 and by now was experienced, yet still young – just 26 years old, which for goalkeepers is not even the peak. No wonder Real Sociedad received so few goals – Arconada was rapidly becoming one of the best European goalkeepers. Perhaps luckily for the club, Arconada appeared when the big clubs had the previous generation of solid keepers still playing well (Iribar, Reina, Sadurni). By 1979-80 the veterans were gone, those of the immediate next generation aged (Garcia Remon and Miguel Angel), Arconada was national team regular, and Real Sociedad was rising – no point to go elsewhere. And he did not – he was in the right club at the right time. His greatest years coincided with the greatest years of Real Sociedad. The best was still to come. As for the picture, Real Sociedad here is dressed in their second kit – since their usual colours will fly for quite some time, let see their lesser known second option.

At a glance – nothing new: Real Madrid champion once again. But it was difficult victory – Real Madird prevailed by a single point, winning a tough race from start to the end. A happy end, but the future did not look bright – Real Sociedad was breathing in the neck of mighty Real Madrid. But for the club and the fans only victory counts – and this season gave them a double, so everybody was happy.

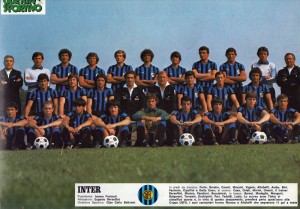

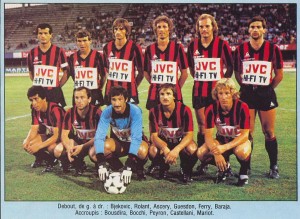

The usual suspects, dressed in blue: standing from left: Garcia Remon, San Jose, Cunningham, Benito, Pirri, Camacho.

The usual suspects, dressed in blue: standing from left: Garcia Remon, San Jose, Cunningham, Benito, Pirri, Camacho.

First row: Stielike, Juanito, Del Bosque, Garcia Hernandez, Santillana.

What can one say? A famous squad. The top Spanish players of the 1970s plus Stielike, already recognized as an international mega-star, and fresh strong addition in Cunningham, who apparently settled well. With Vujadin Boskov at the helm, everything looked just fine. The future was also seemingly bright: Stielike and Cunningham provided a backbone for the years to come. But this team won the championship with difficulty and was far from overwhelming. And as great as these players were, Real Madrid was reduced to domestic victories – internationally, the 1970s were poor. And even poorer was the performance of the Spanish national team, which was based largely on Real’s stars. Stielike and Cunningham had few trophies with their previous clubs and nothing with their national teams. Real was strong, no doubt about it, but not all that strong – the point was not missed by the administration. It was a very successful season, but with a grain of salt.