18-team strong first division, which may be was too big for Belgian football. More or less, 6 clubs were clearly stronger than the rest, then followed a big group of fairly equal teams, and at the bottom – the outsiders, which made life comfortable for most mid-table clubs. SC Hasselt was clearly below everybody else – 16th with 10 points, distinguishing itself with atrocious defensive record: they received 94 goals. Likely the worst defensive record in Europe.

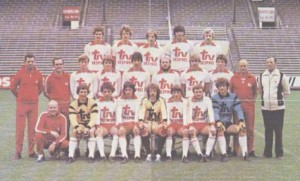

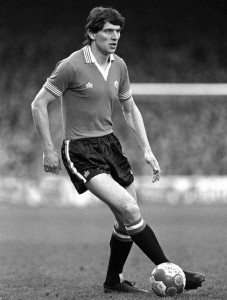

SC Hasselt, or Sporting Club Hasselt, or just Hasselt was far too weak to survive in the top league. It was not they did not try – three foreign players were engaged to help them: the Moroccan striker Larbi Hazzam (28 years old), the West German striker Peter Tomaschewski (25), and finally the Dutchman Peter Ressel, the only well known name in the team. Ressel was part of the strong Feyenoord in the early 1970s, then part of the strong Anderlecht in the middle of the 1970s, and played his bit for the national team of Holland in the glory years. But he grew old… and went to easy living in North America, joining Chicago Stings. His return to Belgium was not glorious – Hasselt obviously hoped he would help, but Ressel was already 35 years old and no longer up to important tasks.

SC Hasselt, or Sporting Club Hasselt, or just Hasselt was far too weak to survive in the top league. It was not they did not try – three foreign players were engaged to help them: the Moroccan striker Larbi Hazzam (28 years old), the West German striker Peter Tomaschewski (25), and finally the Dutchman Peter Ressel, the only well known name in the team. Ressel was part of the strong Feyenoord in the early 1970s, then part of the strong Anderlecht in the middle of the 1970s, and played his bit for the national team of Holland in the glory years. But he grew old… and went to easy living in North America, joining Chicago Stings. His return to Belgium was not glorious – Hasselt obviously hoped he would help, but Ressel was already 35 years old and no longer up to important tasks.

If SC Hasselt was quite predictably too weak for the top division, the club finishing just above them was usually a mid-table performer. It may had been unfortunate season of lousy form; it may had been lack of chemistry. Decline would be too strong a word for SC Charleroi – they were never great. But given the squad, their terrible performance was surprising too.

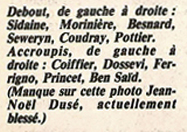

8 wins, 6 ties, 20 losses – 22 points at the end. 4 less than the club above them and relegated. Having been much stronger than SC Hasselt was no comfort. Going to second division was even less comfortable. Charleroi were small, but hardly the outsiders and it was even stranger, when one takes a look at the team: may be their Luxembourg players were not much, but if Nico Rohmann hardly rings any bell, Nico Braun have been well respected name in France, where he spent many years. The Dutch midfielder Chris Dekker was not famous either and 35 years old on top of everything, but he also had fairly good earlier career. Their captain was West German – Rainer Gebauer was with Charleroi since 1974, but he played for FC Koln before moving to Belgium. The last and may be most interesting name was Alexandre Czerniatinski, 20-years old up and coming talent. May be the most promising Belgian youngster at the moment. Apart from going down to second division, there is something else interesting and difficult to figure out: Czerniatinski was listed as Polish, thus, in the group of foreign players. Yet, the ‘foreigner’ was Belgian-born, playing for the Belgian national youth teams, and considered a prime candidate for A-national team. Why was he listed as foreigner is unclear, but he was not alone – his team-mate Antonio Iezzi was listed as an Italian, but hist professional status was ‘Belgian player’. Same with the coach Jean Piccinin. In the same time there were players in the league with clearly un-Belgian names listed simply as Belgians. Hard to tell what made the difference, but confusing it was and is, for it was difficult to distinguish foreign imports from domestic players, especially when Eastern Europeans were concerned: who was runaway refugee, who was Belgian-born, and who was proper import? This confusing issue was also applicable to African players.

8 wins, 6 ties, 20 losses – 22 points at the end. 4 less than the club above them and relegated. Having been much stronger than SC Hasselt was no comfort. Going to second division was even less comfortable. Charleroi were small, but hardly the outsiders and it was even stranger, when one takes a look at the team: may be their Luxembourg players were not much, but if Nico Rohmann hardly rings any bell, Nico Braun have been well respected name in France, where he spent many years. The Dutch midfielder Chris Dekker was not famous either and 35 years old on top of everything, but he also had fairly good earlier career. Their captain was West German – Rainer Gebauer was with Charleroi since 1974, but he played for FC Koln before moving to Belgium. The last and may be most interesting name was Alexandre Czerniatinski, 20-years old up and coming talent. May be the most promising Belgian youngster at the moment. Apart from going down to second division, there is something else interesting and difficult to figure out: Czerniatinski was listed as Polish, thus, in the group of foreign players. Yet, the ‘foreigner’ was Belgian-born, playing for the Belgian national youth teams, and considered a prime candidate for A-national team. Why was he listed as foreigner is unclear, but he was not alone – his team-mate Antonio Iezzi was listed as an Italian, but hist professional status was ‘Belgian player’. Same with the coach Jean Piccinin. In the same time there were players in the league with clearly un-Belgian names listed simply as Belgians. Hard to tell what made the difference, but confusing it was and is, for it was difficult to distinguish foreign imports from domestic players, especially when Eastern Europeans were concerned: who was runaway refugee, who was Belgian-born, and who was proper import? This confusing issue was also applicable to African players.

No confusion with the team which finished at the safe 16th place – Berchem Sports had no foreign players, so untypical for a Belgian club.

To a point, Berchem was good surprise: without a single recognizable name and normally playing second division football, they were expected to be relegated. But the anonymous squad fought to the end, outscoring 7 clubs. They were not even in danger of relegation at the final stage of the championship, so it was quite a success, however small. They lost 15th place on worse goal-difference.

To a point, Berchem was good surprise: without a single recognizable name and normally playing second division football, they were expected to be relegated. But the anonymous squad fought to the end, outscoring 7 clubs. They were not even in danger of relegation at the final stage of the championship, so it was quite a success, however small. They lost 15th place on worse goal-difference.

Like Berchem, Beringen finished with 26 points, but having better goal-difference, they took 15th place. Lucky, unlucky, Beringen was historically similar to Berchem and Hasselt – more familiar with second division than the first, so nothing surprising in their final standing: they survived.

What can be said of them? An additional point to the mystery of who was and who was not domestic player: if the Polish and Italian sounding names in Charleroi were listed as foreigners, it was the opposite here. Both Zenon Ziembicki and Paolo Russo were listed as Belgians. The rest of ‘strange’ names were pure imports, suggesting better place in the final table than the actual one. They all came from Holland, the country supplying the bulk of foreign players to Belgian clubs, but two of the three were not Dutch. The Yugoslavian defender Nicola Budisic came from NAC Breda, the other two from far more impressive club: PSV Eindhoven. The Welsh Nick Deacy and the Dutch Gerry Deykers. On the surface, looked like serious recruits – unless one sees the age of the palyers: only Deacy was under 30. Budisic was 33 and Deykers – 34. Clearly, at their last legs. Which was nothing, compared to the truly big name playing for Beringen: Wilfried van Moer was 35. To most, a goner… listed as ‘ex-national team player’. His heavy injuries moved him away from spotlights and from Standard (Liege) years ago. Who could tell what was coming? Van Moer had excellent season, was included again in the national team, and was one of the greatest stars at the 1980 European Championship finals. He was Beringen, the motor, the inspiration, the reason the club managed to perform relatively well and staying in the top league. A big and very unusual revival, especially considering the lowly club van Moer played with. A true star, something rare for a lowly club at the bottom of the league.

What can be said of them? An additional point to the mystery of who was and who was not domestic player: if the Polish and Italian sounding names in Charleroi were listed as foreigners, it was the opposite here. Both Zenon Ziembicki and Paolo Russo were listed as Belgians. The rest of ‘strange’ names were pure imports, suggesting better place in the final table than the actual one. They all came from Holland, the country supplying the bulk of foreign players to Belgian clubs, but two of the three were not Dutch. The Yugoslavian defender Nicola Budisic came from NAC Breda, the other two from far more impressive club: PSV Eindhoven. The Welsh Nick Deacy and the Dutch Gerry Deykers. On the surface, looked like serious recruits – unless one sees the age of the palyers: only Deacy was under 30. Budisic was 33 and Deykers – 34. Clearly, at their last legs. Which was nothing, compared to the truly big name playing for Beringen: Wilfried van Moer was 35. To most, a goner… listed as ‘ex-national team player’. His heavy injuries moved him away from spotlights and from Standard (Liege) years ago. Who could tell what was coming? Van Moer had excellent season, was included again in the national team, and was one of the greatest stars at the 1980 European Championship finals. He was Beringen, the motor, the inspiration, the reason the club managed to perform relatively well and staying in the top league. A big and very unusual revival, especially considering the lowly club van Moer played with. A true star, something rare for a lowly club at the bottom of the league.

If Beringen outdid itself somewhat, the team just above them perhaps underperformed. Van Moer made news this season, but not the players of Beerschot, as one could expect. A curious team, which mostly deserves attention for historic and political reasons. On the field, they were nothing… with 27 points, they finished 14th.

The coach was Ladislav Novak, a star Czechoslovakian national team player once upon a time, who captained the silver medalists of the 1962 World Cup. As a coach, he was coach of the Czechoslovakian in the 1971-72 and in 1974 went to work in Belgium. Beerschot was the third club he coached, after Antwerpen and Lokeren. Colourful coach with colourful players: Jan Tomaszewski joined Beerschot after the 1978 World Cup. Now he was 32, not a fatal age for a goalkeeper, but one of the most famous goalkeepers of the 1970s playing for lowly club? Popular bios of Tomaszewski claim persection: he was not allowed to go abroad before turning 30 by the Polish government. Was it true is very hard to tell: Tomaszewski is known as a very outspoken, even controversial critic both of football and usual politics in Poland, but this is largely due to his activities after 1989. Back in the 1970s the normal Polish practice was to permit players to go professional in the West after they turned 28 and were not needed for the national team anymore. Tomaszewski was the number one national team goalkeeper until the 1978 World Cup, so delay of transfer may have been due to that, but the matter was not in the hands of the Polish government, but of the Football Federation. Tomaszewski was clearly in decline at the 1978 World Cup and lost his position during the finals. He was no longer coveted player when he was permitted to go abroad, which may be explaining why he ended in Beerschot. But decisions for foreign transfers made in the old Communist countries fail logical continuity of policy, so reasons remain largely mysterious: Tomaszewski was a big name, but in 1979 another Pole joined Beerschot – Stanyslas Gzyl from Gornik (Zabrze). He was 31 at the time of the transfer and never played for Poland – a rather anonymous player. Both the star and the unknown ended in Beerschot, God knows why. As for Tomaszewski, going to Beerschot made a strange reunion too – Emanuel Sanon was a veteran of the team, playing for it since 1974. Since the 1974 World Cup, that is, when the Haitian striker scored much talked about goal against Italy. Poland and Haiti were in the same preliminary group, so the former opponents met again after 4 years, this time as team-mates. Both emerged from obscurity at the 1974 World Cup, but Sanon got a contract right away – Tomaszewski had to wait, and if for the Haitian Beerschot was more or less the highest point of his career, for Tomaszewski was a step down. May be even two steps down. Yet, the two Poles and the Haitian were not the whole foreign contingent of Beerschot: a Zairian young and talented defender was in the squad, Paul Beloy Beloy. 23 years old, who came to Belgian football after a short spell in West Germany. The usual Dutch presence – Rene Mucher, who was with the club as long as Sanon. Another very young striker arrived in 1979 – 22-years old Chilean, formerly of Colo-Colo, Luis Echeverra Mena. Unknown player, but interesting anyhow, for Mena was a rare South American joining European club north from Spain and France. If most of the foreigners were either unknown or of faded fame, another two were different: Julien Cools, already 33, but still considered a national team material, arrived from FC Brugge. Classy midfielder, may be too old for his former club, but fine for a smaller one. Cools was known as ‘marathon man’ and key player during the great European years of FC Brugge. Juan Lozano, 25 years old, played along Cools in Beerschot, still listed as foreigner. Soon the Spaniard will be naturalized and included in the Belgian national team – but fame was yet to come. Beerschot had impressive squad, it seems, but failed to deliver. The stars were over the hill perhaps and the other foreigners – not good enough.

The coach was Ladislav Novak, a star Czechoslovakian national team player once upon a time, who captained the silver medalists of the 1962 World Cup. As a coach, he was coach of the Czechoslovakian in the 1971-72 and in 1974 went to work in Belgium. Beerschot was the third club he coached, after Antwerpen and Lokeren. Colourful coach with colourful players: Jan Tomaszewski joined Beerschot after the 1978 World Cup. Now he was 32, not a fatal age for a goalkeeper, but one of the most famous goalkeepers of the 1970s playing for lowly club? Popular bios of Tomaszewski claim persection: he was not allowed to go abroad before turning 30 by the Polish government. Was it true is very hard to tell: Tomaszewski is known as a very outspoken, even controversial critic both of football and usual politics in Poland, but this is largely due to his activities after 1989. Back in the 1970s the normal Polish practice was to permit players to go professional in the West after they turned 28 and were not needed for the national team anymore. Tomaszewski was the number one national team goalkeeper until the 1978 World Cup, so delay of transfer may have been due to that, but the matter was not in the hands of the Polish government, but of the Football Federation. Tomaszewski was clearly in decline at the 1978 World Cup and lost his position during the finals. He was no longer coveted player when he was permitted to go abroad, which may be explaining why he ended in Beerschot. But decisions for foreign transfers made in the old Communist countries fail logical continuity of policy, so reasons remain largely mysterious: Tomaszewski was a big name, but in 1979 another Pole joined Beerschot – Stanyslas Gzyl from Gornik (Zabrze). He was 31 at the time of the transfer and never played for Poland – a rather anonymous player. Both the star and the unknown ended in Beerschot, God knows why. As for Tomaszewski, going to Beerschot made a strange reunion too – Emanuel Sanon was a veteran of the team, playing for it since 1974. Since the 1974 World Cup, that is, when the Haitian striker scored much talked about goal against Italy. Poland and Haiti were in the same preliminary group, so the former opponents met again after 4 years, this time as team-mates. Both emerged from obscurity at the 1974 World Cup, but Sanon got a contract right away – Tomaszewski had to wait, and if for the Haitian Beerschot was more or less the highest point of his career, for Tomaszewski was a step down. May be even two steps down. Yet, the two Poles and the Haitian were not the whole foreign contingent of Beerschot: a Zairian young and talented defender was in the squad, Paul Beloy Beloy. 23 years old, who came to Belgian football after a short spell in West Germany. The usual Dutch presence – Rene Mucher, who was with the club as long as Sanon. Another very young striker arrived in 1979 – 22-years old Chilean, formerly of Colo-Colo, Luis Echeverra Mena. Unknown player, but interesting anyhow, for Mena was a rare South American joining European club north from Spain and France. If most of the foreigners were either unknown or of faded fame, another two were different: Julien Cools, already 33, but still considered a national team material, arrived from FC Brugge. Classy midfielder, may be too old for his former club, but fine for a smaller one. Cools was known as ‘marathon man’ and key player during the great European years of FC Brugge. Juan Lozano, 25 years old, played along Cools in Beerschot, still listed as foreigner. Soon the Spaniard will be naturalized and included in the Belgian national team – but fame was yet to come. Beerschot had impressive squad, it seems, but failed to deliver. The stars were over the hill perhaps and the other foreigners – not good enough.

13th, a point ahead of Beerschot VAV, finished Antwerpen. If Beerschot had players suggesting higher place, their city rivals should have been higher in the table for historic reasons – never great, but usually stronger than most Belgians clubs.

Royal Antwerp or Antwerpen, or FC Antwerp… there are always confusing variations of the names of Belgian clubs, perhaps failed to recruit strong players. May be money was short, may be vision. Compared to Beerschot, Antwerpen was almost anonymous squad, lacking foreigners. Theo Custers was the big star – national team goalkeeper, losing the competition with Pfaff, but the second-best in the country at the time. The only import was Polish veteran – Miroslav Justek, 32-years old former Lech (Poznan) striker, who occasionally played for the Polish national team. A marginal player – may be solid, but never a star, and virtually unknown in Europe. That was all Antwerpen had this year, so finishing low was hardly a surprise. Yet, they finished above their city rivals. With this ends the lower group of the mid-table clubs – slightly underperforming than the others.

Royal Antwerp or Antwerpen, or FC Antwerp… there are always confusing variations of the names of Belgian clubs, perhaps failed to recruit strong players. May be money was short, may be vision. Compared to Beerschot, Antwerpen was almost anonymous squad, lacking foreigners. Theo Custers was the big star – national team goalkeeper, losing the competition with Pfaff, but the second-best in the country at the time. The only import was Polish veteran – Miroslav Justek, 32-years old former Lech (Poznan) striker, who occasionally played for the Polish national team. A marginal player – may be solid, but never a star, and virtually unknown in Europe. That was all Antwerpen had this year, so finishing low was hardly a surprise. Yet, they finished above their city rivals. With this ends the lower group of the mid-table clubs – slightly underperforming than the others.

There was a middle mid-table group of 6 teams, which were slightly stronger than lower group, but also slightly weaker than three clubs. Not much stronger, not much weaker… the general similarity of these clubs was in their makes: they all depended on few strong players and various foreigners, normally middle-of-the-road professionals. KSV Waregem finished 12th , 3 points ahead of Antwerpen.

Of course, nobody expected miracles from Waregem – more or less, they played as ever. Not very strong, not very weak. Strong Dutch presence, beginning with the coach – Hans Croon. The players were available in every line – Rene de Jong (goalkeeper), Henny Michielsen (midfield), Pieter de Waardt, and Roland Hendricks (strikers). Nobody recognizable, but there was a difference – if the so far mentioned clubs used old veterans, Waregem had younger foreigners. Nothing special, but experienced and at their prime. The key players of the team were domestic, however – the national team defenders Marc (30 years old) and Luc (29) Millecamps. Marc was Waregem’s captain, but immediately after the end of the season Luc became famous for his performance at the 1980 European Championship. Waregem had no great squad, heavily dependent on the form of Millecamps brothers -and two players were able to keep the team at 12th place, but hardly moving it higher.

Of course, nobody expected miracles from Waregem – more or less, they played as ever. Not very strong, not very weak. Strong Dutch presence, beginning with the coach – Hans Croon. The players were available in every line – Rene de Jong (goalkeeper), Henny Michielsen (midfield), Pieter de Waardt, and Roland Hendricks (strikers). Nobody recognizable, but there was a difference – if the so far mentioned clubs used old veterans, Waregem had younger foreigners. Nothing special, but experienced and at their prime. The key players of the team were domestic, however – the national team defenders Marc (30 years old) and Luc (29) Millecamps. Marc was Waregem’s captain, but immediately after the end of the season Luc became famous for his performance at the 1980 European Championship. Waregem had no great squad, heavily dependent on the form of Millecamps brothers -and two players were able to keep the team at 12th place, but hardly moving it higher.

With 32 points, SK Beveren finished 11th. The surprise champions of 1978-79 plummeted down the very next season and understandably so – the club had no means for making truly strong team. The good players were few and there were part-timers. However, this was the best period in the history of modest Beveren – there will be more about them a bit later.

With 32 points, SK Beveren finished 11th. The surprise champions of 1978-79 plummeted down the very next season and understandably so – the club had no means for making truly strong team. The good players were few and there were part-timers. However, this was the best period in the history of modest Beveren – there will be more about them a bit later.

KSV Cercle Brugge was 10th – 32 points, but better goal-difference than Beveren. True to their predicament – their home city, as practically every Belgian town, was hardly able to maintain two strong professional clubs at the same time. FC Brugge already was the big club, so Cercle Brugge had no chance.

They were like Waregem, the same ilk: depending on the form of one or two strong players. In their case, on the veteran Dutch defender Bram van Kerkhof, and the better known Danish national team striker Soren Skov. The best known player was also defender and Dutch – Kees Krijgh, 30-years old newcomer from PSV Eindhoven. That is, one of the regulars of the great PSV Eindhoven of the 1970s, a team already aging and getting rid of players getting too old. Krijgh was never a great star, nor he was a national team player, but was famous enough as a regular of PSV Eindhoven during its best years. With him, van Kerkhof, and Skov, Cercle Brugge was able to maintain their normal position in the league.

They were like Waregem, the same ilk: depending on the form of one or two strong players. In their case, on the veteran Dutch defender Bram van Kerkhof, and the better known Danish national team striker Soren Skov. The best known player was also defender and Dutch – Kees Krijgh, 30-years old newcomer from PSV Eindhoven. That is, one of the regulars of the great PSV Eindhoven of the 1970s, a team already aging and getting rid of players getting too old. Krijgh was never a great star, nor he was a national team player, but was famous enough as a regular of PSV Eindhoven during its best years. With him, van Kerkhof, and Skov, Cercle Brugge was able to maintain their normal position in the league.

RFC Liégeois or RFC Liege, was 9th, a club in the same predicament as Beerschot and Cercle Brugge: the smaller club in the city. Hence, mid-table position was the most they could do and the usual too. 33 points and the same as their immediate neighbours.

The Yugoslav Silvester Takac was the coach and he is mostly interesting as a footnote in the evolution of the Yugoslavian national team – in 1972 he ans Josip Skoblar offered their services to the national team, stirring perhaps the first serious debate about inclusion of foreign based player in the national team of Yugoslavia. The offer was turned down, but a crack was opened and by 1979-80 it was common practice. Since Takac played in Belgium, he knew local football and was well known in return, so it was hardly a surprise he coached RFC Liege. As for his squad, it was typical Belgian squad… largely unknown Belgians, the inevitable Dutch – Hendrik Medik, and another Dutch, listed as already naturalized – Matthijs van Toorn. Class was provided by Takac’s countryman – Edhem Sljivo, already 30-years old former midfielder of FK Sarajevo and national team player. Sljivo was highly talented – technical, imaginative, creative – but somewhat unlucky. He was actual national team player, but his appearances for Yugoslavia were rare – between 1976 and 1982 he played only 12 games, scoring 2 goals. The problem was not his capability, but the competition – unfortunately, there were strong midfielders when he was young, when he was at his peak, and when he was getting old. He coincided with Branko Oblak, not to mention others. Perhaps that was the reason he ended in lowly RFC Liege – and jumping a bit ahead, progressed from there to France and West Germany, something very unusual for a player ‘discovered’, so to say, at 30. It could be said, that his contribution kept RFC Liege in good place.

The Yugoslav Silvester Takac was the coach and he is mostly interesting as a footnote in the evolution of the Yugoslavian national team – in 1972 he ans Josip Skoblar offered their services to the national team, stirring perhaps the first serious debate about inclusion of foreign based player in the national team of Yugoslavia. The offer was turned down, but a crack was opened and by 1979-80 it was common practice. Since Takac played in Belgium, he knew local football and was well known in return, so it was hardly a surprise he coached RFC Liege. As for his squad, it was typical Belgian squad… largely unknown Belgians, the inevitable Dutch – Hendrik Medik, and another Dutch, listed as already naturalized – Matthijs van Toorn. Class was provided by Takac’s countryman – Edhem Sljivo, already 30-years old former midfielder of FK Sarajevo and national team player. Sljivo was highly talented – technical, imaginative, creative – but somewhat unlucky. He was actual national team player, but his appearances for Yugoslavia were rare – between 1976 and 1982 he played only 12 games, scoring 2 goals. The problem was not his capability, but the competition – unfortunately, there were strong midfielders when he was young, when he was at his peak, and when he was getting old. He coincided with Branko Oblak, not to mention others. Perhaps that was the reason he ended in lowly RFC Liege – and jumping a bit ahead, progressed from there to France and West Germany, something very unusual for a player ‘discovered’, so to say, at 30. It could be said, that his contribution kept RFC Liege in good place.

FC Winterslag had typical for that time season – right in the middle of the table. 12 wins, 11 ties, 11 losses, but rather unusual low scoring record. Belgian league normally was above the average of most countries, so 35 goals scored in 34 games seemed quite low, especially if compared to the first 10 clubs in the final table. Only 4 clubs scored less than Winterslag and it looked like the club depended heavily on domestic matches, scoring a goal and trying to keep its minimal advantage to get the points. Away, they did not care much… their defense was leaky, they received 62 goals and only the relegated two teams allowed more goals in their net. But it was all normal at the end – 8th place, 2 points ahead of RFC Liege.

Winterslag had young talented coach – Robert Waseige – who apparently utilized a limited team to the best. The squad was typical – the inevitable almost unknown Dutch players, Vim van Woerkum and Toon Wouters, and Belgian-raised, if not Belgian-born Italians, Licio D’Onofrio and Raimond Baiamonde. The only big name was Johan de Vrindt – long time national team regular and one of the top Belgian strikers for many years. But he was already 35 and inevitably his career was going downhill: he played for FC Brugge and Anderlecht at his prime, then moved a notch down to Lokeren, and from there to Winterslag. Still, his presence was important and perhaps the riving force of the otherwise modest team.

Winterslag had young talented coach – Robert Waseige – who apparently utilized a limited team to the best. The squad was typical – the inevitable almost unknown Dutch players, Vim van Woerkum and Toon Wouters, and Belgian-raised, if not Belgian-born Italians, Licio D’Onofrio and Raimond Baiamonde. The only big name was Johan de Vrindt – long time national team regular and one of the top Belgian strikers for many years. But he was already 35 and inevitably his career was going downhill: he played for FC Brugge and Anderlecht at his prime, then moved a notch down to Lokeren, and from there to Winterslag. Still, his presence was important and perhaps the riving force of the otherwise modest team.

Waterschei took 7th place, 2 points ahead of Winterslag – both clubs were often at the same level, practically running together and finishing in somewhat mini-rivalry in the middle of the league.

Waterschei were almost a copy of Winterslag – good coach, few anonymous, but reliable foreigners, and one player, who may be considered a star of the team. But Waterschei achieved much more than Winterslag this season.

Waterschei were almost a copy of Winterslag – good coach, few anonymous, but reliable foreigners, and one player, who may be considered a star of the team. But Waterschei achieved much more than Winterslag this season.

With them, the bulk of the league is almost complete – fairly equal clubs of the same make, depending on largely aging domestic and foreign stars, and having practically no future stars in their squads. Two more clubs belonged to the big group, but they were different, presenting a cutting edge between the leaders and the rest, so they will be placed among the top teams.

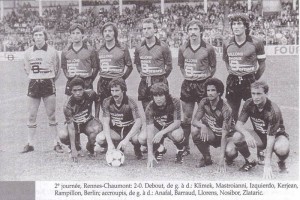

Stade Rennes ended 2nd, but… they had 20 wins, 7 ties, and 6 losses. This makes 47 points, not 46. There is no indication for some penalty deducting a point from their record, so the only other reason would be a statistical mistake. Confusing that, for Rennes ended with better goal-difference than Guingamp and whether the points were real or not, they finished above Guingamp. But it was not important, because only one team was getting promoted and Rennes was not exactly a contender.

Stade Rennes ended 2nd, but… they had 20 wins, 7 ties, and 6 losses. This makes 47 points, not 46. There is no indication for some penalty deducting a point from their record, so the only other reason would be a statistical mistake. Confusing that, for Rennes ended with better goal-difference than Guingamp and whether the points were real or not, they finished above Guingamp. But it was not important, because only one team was getting promoted and Rennes was not exactly a contender. Their logo gives 1951 as founding year, but the club was much older – founded in 1919, although under different name. Which they changed, and then changed again to their present name. The city of Tours has Celtic roots and the name comes from the name of the settlers, belonging to the tribe or clan Turon. Hence the motto of the club, borrowed from the city’s motto. Sounds brave and proud, but the club was modest and remained modest. At last a victory.

Their logo gives 1951 as founding year, but the club was much older – founded in 1919, although under different name. Which they changed, and then changed again to their present name. The city of Tours has Celtic roots and the name comes from the name of the settlers, belonging to the tribe or clan Turon. Hence the motto of the club, borrowed from the city’s motto. Sounds brave and proud, but the club was modest and remained modest. At last a victory.

![dynamo-tbilisi--1980[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/dynamo-tbilisi-19801-300x177.jpg)