Dominance is relative term – 4 Ukrainian clubs played in first division in 1980 vs 8 Russian, of which 5 represented Moscow, so the great Moscow – Kiev rivalry was 5-1. Kind of, for in fact it was just Spartak vs Dinamo, Beskov vs Lobanovsky. 1980 season kept the formula tried earlier and considered helpful: a limit of 10 ties. Any tie above the limit gave no point. The clubs learned the lesson at last – only 6 clubs went above limit. Dinamo (Moscow) had the seasonal record of 14 ties, which was low number compared to what have been two-three years ago. Attacking football was making its way, but scoring was still low and new trend was observed with some alarm: the league was becoming home-match oriented. The number of points earned away, never very high anyway, decreased. Most of the league was not great, but at least there were no outsiders this year – more or less, all were competitive. Final positions depended largely on the makings of the teams – with one exception, most teams finished in positions corresponding to the number of good players in each of them. Lokomotiv (Moscow) had no outstanding players and finished last.

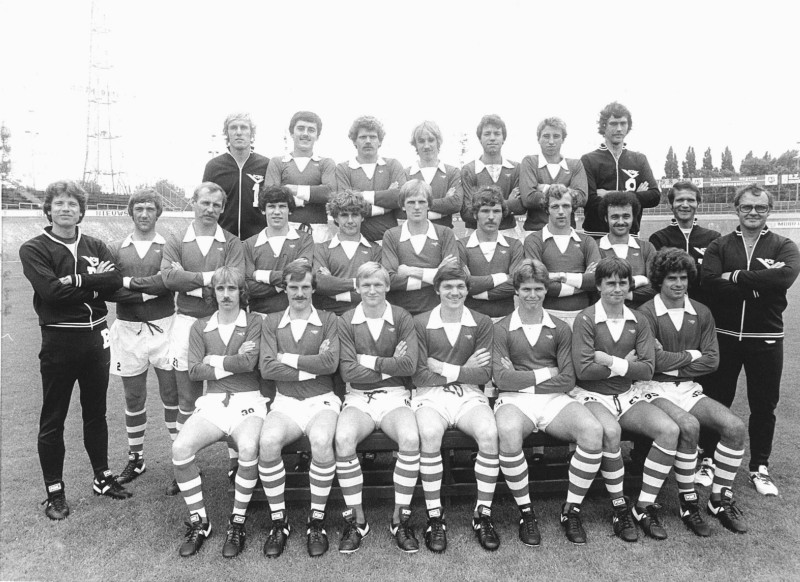

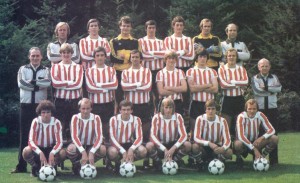

Crouching from left: Gleb Kolesnikov – doctor, Anatoly Shelest, Viktor Budnik, Vladimir Mukhanov, Sergey Baburin.

Crouching from left: Gleb Kolesnikov – doctor, Anatoly Shelest, Viktor Budnik, Vladimir Mukhanov, Sergey Baburin.

Middle row: Aleksander Gassov – masseur, Viktor Maryenko – coach, Nikolay Badussov, Petr Slobodyan, Anatoly Mashkov – administrator, Boris Petrov – assistant coach, Aleksander Averyanov.

Third row: Igor Avvakumov – team chief, Anatoly Solovyev, Evgeny Aleksandrov, Boris Kuznetzov, Sergey Kamzulin, Nikolay Kalaychev, Valery Staferov – assistant coach, Aleksey Mikhaylov.

Petr Slobodyan was perhaps the most famous player in the squad, but he was no longer the promising young player – the very reason he was now playing for Lokomotiv, which was in decline for years and unable to gather a decent team. It was not that Lokomotiv gave up, but they lacked strength and earned 25 points, which placed them at the bottom.

A point above them finished Karpaty (Lvov) – technically, they lost on worse goal-difference, but even if they had better one, their immediate rival was to stay in first division – because of the air disaster, killing almost the whole team the previous year, Pakhtakor (Tashkent) were excepted from relegation. Karpaty suffered from lack of experience more than anything else: it was very young squad. Talented, but uneven – thus, Yurchishin, who attracted the eye of the national team coach when still playing in the second division, now had mediocre season. On the other hand, the right full back O. Rodin played for the national team in 1980. May be hard to believe, but Karpaty had Yu. Susloparov, A. Bal, and V. Ratz in the squad this year. Plus Dumansky and Batich, who were considered sure stars in near future – more promising at the moment than the trio above. Unfortunately, Karpaty needed 29 points to stay in the league, but finished with 26. Down they went again.

One Russian and one Ukrainian club were relegated, a parity in misfortune between Ukraine and Russia, but the newcomers were both Ukrainian. Apart from the relegated and Pakhtakor, which should be excepted from judgment for the reason they needed time to build a new team, the low point of the season was Dinamo (Moscow).

Dinamo finished 14th , barely 2 points ahead of relegation zone. Dinamo lost its leading position during the 1970s, but coming close to relegation was too much, considering the team they had. Perhaps the most experienced and the deepest squad in the league, full of former and current national team players. The usually employed excuse – too many things to handle (championship, cup tournament, UEFA Cup, national and Olympic team duties) – is rather lame.

Dinamo finished 14th , barely 2 points ahead of relegation zone. Dinamo lost its leading position during the 1970s, but coming close to relegation was too much, considering the team they had. Perhaps the most experienced and the deepest squad in the league, full of former and current national team players. The usually employed excuse – too many things to handle (championship, cup tournament, UEFA Cup, national and Olympic team duties) – is rather lame.

On the other hand the team which finished just below Dinamo – Kuban (Krasnodar) – may be considered a success. They were debutantes this season and managed to survive.

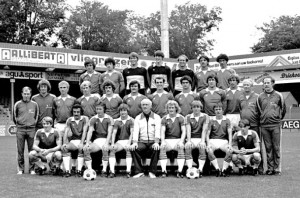

Crouching from left: I. Grishin, V. Gaponenko, S. Goryukov, I. Kaleshin, R. Hassanov, A. Ploshnik.

Crouching from left: I. Grishin, V. Gaponenko, S. Goryukov, I. Kaleshin, R. Hassanov, A. Ploshnik.

Middle row: A. Chakholyantz – doctor, A. Ovchinnikov, A. Chugunov, Yu. Semin, A. Semenyukov, Yu. Chebotarev, V. Shitikov, E. Antonyantz – coach, V. Sereda – team chief.

Third row: V. Beloussov – coach, P. Kusht – coach, E. Polovinko, S. Andreychenko, V. Fursa, A. Artemenko, A. Balakhnin, V. Lagoyda, V. Erkovich, V. Komarov, ?.

15th place is hardly something to brag about, but consider that Kuban had only a handful players with first division experience and never played at top level before – yet, they finished equal to famous Dinamo (Moscow), both teams with 28 points and both teams scored exactly the same number of goals – 32 in 34 matches. Only worse goal-difference placed Kuban below Dinamo.

Torpedo (Moscow) improved a bit, finishing 11th this year, but essentially they shared the same problem with Dinamo (Moscow) – experienced, but disinterested squad.

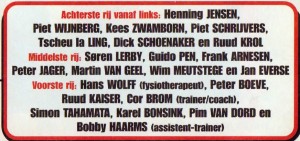

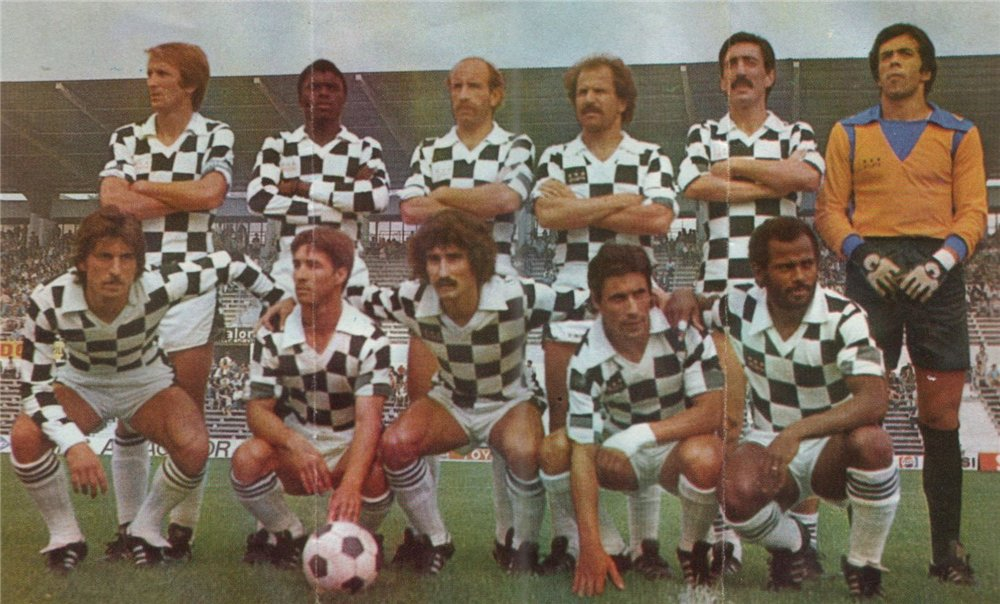

Top row from left: A. Petrov – masseur, V. Yurin, A. Redkous, N. Vassiliev, V. Chanov, N. Kazantzev, V. Kruglov, V. Sakharov, S. Prigoda.

Middle row: Yu. Zolotov – team chief, N. Senyukov – assistant coach, E. Khrabrostin, V. Buturlakin, A. Zarapin, S. Petrenko, A. Kodylev, V. Zhupikov, A. Minaev, V. Zhendarev – administrator, A. Proyaev – doctor, V. Salkov – coach.

Crouching: V. Pimushin, M. Chesnokov, G. Salov, Yu. Kovalev, Yu. Khlopotnov, M. Smirnov, V. Galayba.

Perhaps the most interesting figure in the team was a newcomer from Shakhter (Donetzk) – the goalkeeper Vyacheslav Chanov. He may serve as a test against both Dinamo and Torpedo – back at home, he was constant a reserve. At 29, he appeared in only 78 matches and faced pressure from two sides – from the regular keeper and national team choice Degtyarev and from his younger brother Viktor Chanov. Yet, Vyacheslav Chanov was talented keeper and even considered national team candidate – but hardly ever played, so he moved to e reputable club where he became instantly a starter. Both Dinamo and Torpedo had this problem with quite a few players, but both the clubs and the players chose not to make a move. Thus, to a point, Dinamo’s goalkeepers Pilguy and Gontar aged together with one sitting on the bench – whoever played at the moment was called to the national team too, but the other often missed a whole season. Or two – Gontar, at 31, had 112 official games and Pilguy, 32 – 188. But it looked like that both were happy just to sit and watch than to play regularly outside Moscow – and they were not exceptions in both Dinamo and Torpedo.

The league was tightly going up to 5th place, occupied by CSKA (Moscow) with 35 points. Then a gap occurred – Dinamo (Tbilisi) finised 3 points ahead of CSKA, but also 3 points behind the bronze medalists. The Georgians had fine season, but never were a title contender. The bronze medalists were not fighting for the title either – they finished 3 points behind the second placed and ended 9 points less than the champions. But they had splendid season, their best in years, for Zenit (Leningrad) normally were mid-table club, hardly worth mentioning. Suddenly they came to life.

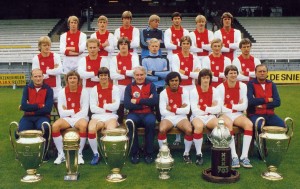

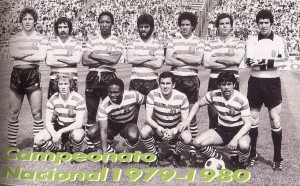

Standing from left: V. Khrapovitzky – assistant coach, S. Shvetzov, Yu. Timofeev, V. Klementiev, Yu. Zheludkov, V. Melnikov – doctor, M. Yudkovich – administrator, V. Golubev, A. Stepanov, S. Bondarenko, V. Kazachenok, P. Sadyrin – assistant coach.

Standing from left: V. Khrapovitzky – assistant coach, S. Shvetzov, Yu. Timofeev, V. Klementiev, Yu. Zheludkov, V. Melnikov – doctor, M. Yudkovich – administrator, V. Golubev, A. Stepanov, S. Bondarenko, V. Kazachenok, P. Sadyrin – assistant coach.

Sitting: A. Tkachenko, Yu. Gerasimov, I. Yakovlev, S. Vedeneev, Yu. Morozov – coach, A. Davydov, V. Kornev – team chief, N. Larionov, A. Zakharikov, M. Biryukov.

A solid team, yet nothing special – a typical Zenit’s squad. Good players, but hardly wetting the appetites of the Moscow clubs (Kazachenok did, but Larionov, one of the strong national players in the 1980s, did not). The reason for the sudden awakening of Zenit may be entirely credited to the coaching staff – Yury Morozov, one of the top Soviet coaches of the 1960s and the 1970s – and his assistant, who soon became famous too – Pavel Sadyrin. As for this squad, it had two things: at the beginning of the season Zenit had the only player in the league with more than 300 championship matches – their goalkeeper Tkachenko – and one face is missing on the this photo, made late in the season – the missing face belongs to the first Soviet player transferred to play professionally in the West.

Spartak (Moscow) was one of the two candidates for the title and the champions of 1979 played bravely until they met Dinamo (Kiev) in the second half of the championship – they lost 0-2 in Kiev and Dinamo got momentum, which left Spartak second at the end.

Spartak was arguably the most promising side, but it was also unfinished team – Beskov was still searching and shaping. The rivalry for the 1980s, however, was established this season – Spartak, after sinking to the second division, came back with vengeance. Dasaev, Khidiatulin, Romantzev, Shavlo, Cherenkov firmly established themselves as the leading Soviet players and still very young Rodionov made himself noticed.

The champion was of course Dinamo (Kiev) – after overcoming Spartak they steadily opened a gap between themselves and the Moscovites, finishing 6 points ahead. Dinamo lost only 4 matches and typically for champions had the best scoring and defensive record. Comfortable, confident victory. Lobanovsky prevailed over Beskov – not that much a victory, but a statement of approach, a philosophy.

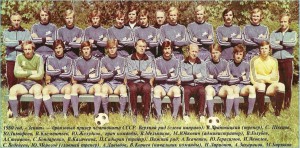

If Spartak had some problems, Dinamo had too. Some were old, going on for years. It was not the team Lobanovsky envisioned and he was clearly going to search further. Rising stars were aplenty, of course, but… Lobanovsky had peculiar attitude to the game: it was very pragmatic and shortcomings made him insisting on iron no-nonsense football. Compared to the great 1975 team, itself accused of robotic kind of playing, the new version was entirely lacking beauty and fantasy. It was compensated by over-physical, often brutal and sometimes cruel style. Atrocious tackles were characteristic. May be there was no other option, given the circumstances and the coach. After the retirement of Rudakov, Lobanovsky was still trying to find agreeable replacement. For instance, both winners of second division had keepers previously tried by Lobanovsky – Dnepr’s regular Krakovsky was Dinamo player at the beginning of the season. Romensky, who spent many years in second division, was the regular, but by the end of the season it looked like his days were over – a new man was found: Mikhail Mikhailov. Jumping a bit ahead, neither goalie lasted long. The goalkeeping problem put pressure on defense, which was also far from perfect. Lozinsky, who even reached the national team, lost his place as right full back to seemingly promising Viktor Kaplun. Kaplun was not the needed player eaither – the problem with this post was almost ten years old already. Even in 1975 the solution was improvisation – midfielder Troshkin was moved back to cover this post. The 1980 version was also improvisation – Lozinsky was played too, as a defensive midfielder, covering Kaplun. It worked well enough, but who remembers either player today? On the left side Demyanenko was the solution, but there were still reservations: he was accused of not coming back to his post quickly enough after running into attack. So, the left side was a bit vulnerable, although not as risky as the right side. The centre of defense was the best – Konkov and Zhuravlyov. But… Konkov was getting too old. Lobanovsky was not particularly fond of aging players. Zhuravlyov was seemingly the key player for the future – or so it looked like in 1980. Lobanovsky had another view – presented by his fielding of players like Boyko, who never raised above the status of reserve (this was his 6th season with Dinamo already – most of the time he played for the second team). Bessonov was ordered to constantly help the defense – in some matches he was even played as pure defender. Defensive line was saturated with Lozinsky and Bessonov, which restrained the attack. Kolotov, already 31, suffered from injuries and clearly his days were coming to end. He played little – Bessonov was not just preferred starter, but made team’s captain: another sign that the veterans were hardly needed. But Veremeev (32) and Buryak (27) were regulars – perhaps out of necessity: Bessonov was creative player, but he was asked to do too many other things, preventing him from playmaking. Thus, Veremeev and Buryak – as a compromise, for Veremeev was not going to last and Buryak soon was to be out of favour and after not so pleasant confrontation with Lobanovsky, out of Dinamo and to another club. For this Buryak is considered a bit of a traitor… Anyhow, the midfield looked temporary – Baltacha, already in the national team, was still a midfielder, but there were signs he will be moved back to defense. He was. But midfield was not in critical state – Bessonov was the guarantee for better days. Attack had a chronic problem: the centre-forward. In 1975 Lobanovsky played without such player, because there was no one good enough for him – and in 1980 there was still nobody good enough to fill the position regularly. Khapsalis, talented as he was, was not constant starter. By now there was a problem at the right wing too – back in 1975 Onishchenko was at hand and Troshkin forayed at the flank, doubling as a winger, but now there was only the young Evtushenko, who played his first official games this year. Lobanovsky liked younger players, but he was also cautious… Evtushenko was already 22 – at this age Blokhin was not only a regular, but a national prime star. Evtushenko was considered too green… which helped Khapsalis a bit, for Lobanovsky never went as far as using just a single striker. Perhaps he had no say on the matter, for Blokhin was pure left-winger and attempts to move him elsewhere failed. Two strikers were needed to balance the situation. Blokhin was the big star as ever, but this season was a bit special – he came back from injuries and his restored form immensely helped Dinamo.

If Spartak had some problems, Dinamo had too. Some were old, going on for years. It was not the team Lobanovsky envisioned and he was clearly going to search further. Rising stars were aplenty, of course, but… Lobanovsky had peculiar attitude to the game: it was very pragmatic and shortcomings made him insisting on iron no-nonsense football. Compared to the great 1975 team, itself accused of robotic kind of playing, the new version was entirely lacking beauty and fantasy. It was compensated by over-physical, often brutal and sometimes cruel style. Atrocious tackles were characteristic. May be there was no other option, given the circumstances and the coach. After the retirement of Rudakov, Lobanovsky was still trying to find agreeable replacement. For instance, both winners of second division had keepers previously tried by Lobanovsky – Dnepr’s regular Krakovsky was Dinamo player at the beginning of the season. Romensky, who spent many years in second division, was the regular, but by the end of the season it looked like his days were over – a new man was found: Mikhail Mikhailov. Jumping a bit ahead, neither goalie lasted long. The goalkeeping problem put pressure on defense, which was also far from perfect. Lozinsky, who even reached the national team, lost his place as right full back to seemingly promising Viktor Kaplun. Kaplun was not the needed player eaither – the problem with this post was almost ten years old already. Even in 1975 the solution was improvisation – midfielder Troshkin was moved back to cover this post. The 1980 version was also improvisation – Lozinsky was played too, as a defensive midfielder, covering Kaplun. It worked well enough, but who remembers either player today? On the left side Demyanenko was the solution, but there were still reservations: he was accused of not coming back to his post quickly enough after running into attack. So, the left side was a bit vulnerable, although not as risky as the right side. The centre of defense was the best – Konkov and Zhuravlyov. But… Konkov was getting too old. Lobanovsky was not particularly fond of aging players. Zhuravlyov was seemingly the key player for the future – or so it looked like in 1980. Lobanovsky had another view – presented by his fielding of players like Boyko, who never raised above the status of reserve (this was his 6th season with Dinamo already – most of the time he played for the second team). Bessonov was ordered to constantly help the defense – in some matches he was even played as pure defender. Defensive line was saturated with Lozinsky and Bessonov, which restrained the attack. Kolotov, already 31, suffered from injuries and clearly his days were coming to end. He played little – Bessonov was not just preferred starter, but made team’s captain: another sign that the veterans were hardly needed. But Veremeev (32) and Buryak (27) were regulars – perhaps out of necessity: Bessonov was creative player, but he was asked to do too many other things, preventing him from playmaking. Thus, Veremeev and Buryak – as a compromise, for Veremeev was not going to last and Buryak soon was to be out of favour and after not so pleasant confrontation with Lobanovsky, out of Dinamo and to another club. For this Buryak is considered a bit of a traitor… Anyhow, the midfield looked temporary – Baltacha, already in the national team, was still a midfielder, but there were signs he will be moved back to defense. He was. But midfield was not in critical state – Bessonov was the guarantee for better days. Attack had a chronic problem: the centre-forward. In 1975 Lobanovsky played without such player, because there was no one good enough for him – and in 1980 there was still nobody good enough to fill the position regularly. Khapsalis, talented as he was, was not constant starter. By now there was a problem at the right wing too – back in 1975 Onishchenko was at hand and Troshkin forayed at the flank, doubling as a winger, but now there was only the young Evtushenko, who played his first official games this year. Lobanovsky liked younger players, but he was also cautious… Evtushenko was already 22 – at this age Blokhin was not only a regular, but a national prime star. Evtushenko was considered too green… which helped Khapsalis a bit, for Lobanovsky never went as far as using just a single striker. Perhaps he had no say on the matter, for Blokhin was pure left-winger and attempts to move him elsewhere failed. Two strikers were needed to balance the situation. Blokhin was the big star as ever, but this season was a bit special – he came back from injuries and his restored form immensely helped Dinamo.

As a whole, the team was unbalanced and rather provisional. Shortcomings were compensated by excellent physical condition, iron discipline, and aggressive intimidation, but what worked at home, did not work in Europe and Lobanovsky was well aware of that. So the search was going to continue… the champions were 5-6 players short of a great team.